Darlina Liu

Interviewed by Katie Grogan, DMH, MA

Darlina Liu is an NYU Grossman School of Medicine student interested in child psychiatry. She completed the Rudin Fellowship in Medical Ethics and Humanities in 2020. She is the author of the children’s book The Bailey Blues and hosts a podcast, “Doctors Who Create,” about creativity in medicine.

Katie Grogan: Bibliotherapy may be an unfamiliar term to many, both inside and outside of medicine. What is it, and how did you become interested in this particular slice of child psychiatry?

Darlina Liu: Bibliotherapy comes from the Greek “biblio” for book and “therapia” for therapy, so it’s the idea of using literature for healing. As a concept, it’s existed for centuries. You’ll find old libraries with inscriptions, describing them as places for healing the soul. As a psychiatric practice, it was popularized in the nineteenth century after Dr. Benjamin Rush recommended reading with patients as part of their treatment. The term itself was later coined by essayist Samuel Crothers. There was an era when psychiatric care was mostly delivered within institutions, and bibliotherapy was a large part of that. With the deinstitutionalization of mental health care over time, bibliotherapy isn’t as commonly practiced now, but I think it still has so much potential.

I grew up reading a lot of children’s books, and they were a crucial part of my schooling and emotional development. That was part of the inspiration for doing a project on bibliotherapy and bringing it back to the modern age.

KG: You chose to focus your research on children’s literature about parental mental illness. Tell me about that decision and how you went about your research.

DL: I had been thinking about this particular population after reading Educated by Tara Westover, which explores the generational impact of mental illness within families. Nature and nurture both play big roles in children of parents with mental illness. There can be a genetic predisposition, which can increase a child’s risk of developing a psychiatric condition, and environmental factors as well.

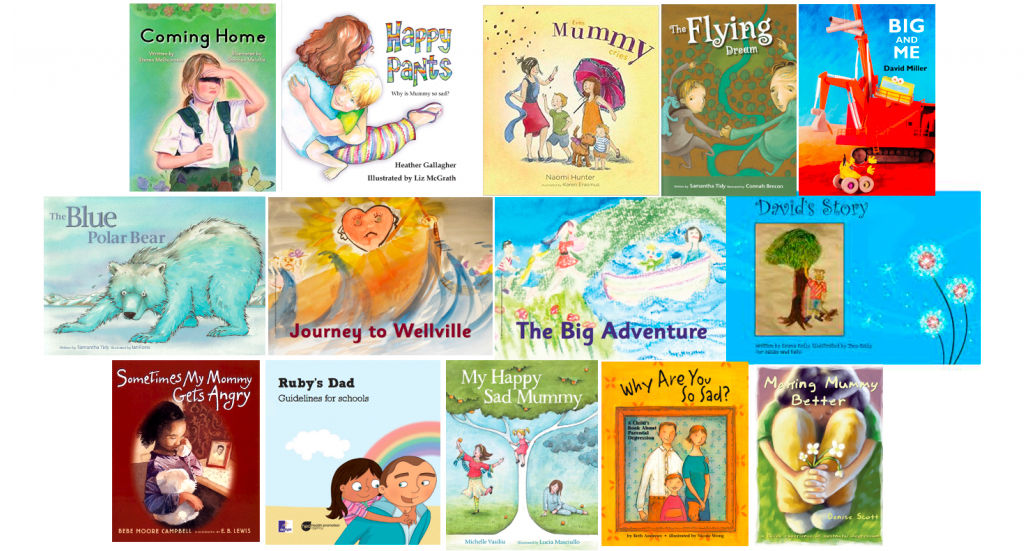

Picture books are relatively low cost and accessible. They comprise an environmental tool that could be harnessed to support kids of parents with mental illness. An initial search didn’t turn up many children’s books on this topic. I soon discovered an organization called Children of Parents with a Mental Illness (COPMI), which has an incredible database of resources, and I knew I hit the jackpot. After applying my search criteria, there were 14 children’s books on specific types of mental illness, which I closely read and analyzed. I looked at which conditions were featured, the accuracy of the diagnostic information as compared to the DSM-5, the accessibility and cost of the books, the reading level, and the identities of the authors.

KG: Which conditions were represented or underrepresented, and why does this matter? What’s at stake when a particular parental mental illness isn’t depicted in children’s literature or when the available books contain misinformation?

DL: Most of the books were about mood disorders and substance use disorders. There were none in the database about parents with anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, or trauma-related disorders. That’s a huge set of illnesses that aren’t being represented and, in those cases, we may not have sufficient resources for children of parents with these particular conditions. There were also some gender biases—for instance, books about bipolar disorder overrepresented mothers and underrepresented fathers. This matters because accurate representation may determine if readers are able to identify with the scenario and may impact the efficacy of bibliotherapy.

In terms of misinformation, we need to take a careful approach before recommending these books for therapeutic purposes. Many of those about bipolar disorder only portrayed manic symptoms and no depressive episodes. It’s critical to show both sides of the story because not doing so can leave someone more confused or unable to understand why their parent with bipolar disorder is having a hard time getting out of bed. Another area of concern was misrepresentation of the treatment and recovery process. One book featured a child making a wish on a star for their parent to get better, and they magically recovered. In my clinical experiences, I’ve never seen an instantaneous psychiatric recovery. It’s an alluring image but not very realistic.

KG: I imagine the backgrounds of the authors impact these depictions. What trends did you observe?

DL: Most of the authors were either parents with psychiatric conditions or their adult children, teachers, or professional children’s authors. A few books were written by individuals with clinical backgrounds, such as licensed social workers.

One reason we don’t see many clinicians writing these books may be that we don’t have ample opportunities in the medical profession to engage in creative pursuits—at least not as many as I would like. I’ve always felt this dichotomy between the sciences and the humanities, this idea that you’re either a science person or a humanities person, but you can’t really inhabit both worlds. Throughout college and medical school, I’ve tried to hold on tight to the humanities. Being able to engage in the medical humanities seminars was really meaningful to me as a way to explore my desire to be creative, to write, and to share that with other people. Things are changing, and there’s more attention on the medical humanities now, but traditionally this has not been emphasized in medical curricula and training. This may contribute to the lack of authors from the medical and scientific community that I observed in my research. But it’s more important than ever that health professionals dialogue with the public about mental illness because it impacts people’s ability to access the services they need.

KG: You met this challenge head on with your own entree into children’s literature. Why and how did you write The Bailey Blues?

DL: After researching this topic for a year with my Rudin Mentor, child and adolescent psychiatrist

Jess Shatkin, MD, I wondered how else I could contribute to this field. That question, combined with my longstanding interest in creative writing, motivated me to create The Bailey Blues. Plus, my German Shephard Bailey was going through a blue spell during the pandemic. She was the perfect main character for the book because it’s based on a true story.

One night, Bailey was lying on the floor and refused to play ball. I thought of the rhyme that opens the book, “Bailey doesn’t want to play ball. Bailey doesn’t want to do anything at all.” I just kept rhyming and actually wrote a full rough draft in that one night. The first iteration was very spontaneous, followed by several rounds of revisions, where I refined the key components and layout of the book, demonstrating what Bailey is like during a depressive episode, then illustrating how she is able to seek help, and finally showing the recovery process, which is not always linear and has its ups and downs.

KG: What contribution to the body of children’s literature about parental mental illness does The Bailey Blues make? What gaps does it fill?

DL: While writing, I kept in mind a wish list of the things the other books didn’t adequately address, such as the doctor’s role in recovery and the experience of relapse. I wanted to ensure that my book featured a diverse cast of characters, reflected in Bailey’s family and the veterinarian. Few of the books I analyzed depicted families of color. That’s a real gap in the literature. When it comes to books on parental mental illness, it helps to have stories that allow readers feel seen. I also wanted to drive home an accurate message about recovery—experiencing some lows is normal and is not a sign of failure; it’s part of process of ultimately getting better. And I didn’t come across any books in the database starring dogs specifically, so that’s another niche area I checked off!

I sent copies of the book to Dr. Shatkin and several other psychiatrists I worked with, and another copy was donated to Bellevue’s Child Inpatient Unit for their book collection.

KG: Going back to the perceived dichotomy between the sciences and the humanities, how has the Rudin Fellowship and The Bailey Blues shaped your identity as a future physician and as a writer?

DL: So much so! Prior to this project, I felt a little bit lost in the research world. In doing the Rudin Fellowship, everything clicked together for me. I thought, “Wow, this is the kind of research that I’m really excited about.” It helped me figure out what I want my academic path to look like. And I’d love to delve deeper into bibliotherapy. There’s little out there about its efficacy because there haven’t been many experiments looking at how children feel before and after they read a text. That could be the next step in this research.

KG: What opportunities have come out of the Rudin Fellowship, and what’s next for you?

DL: I presented this research at the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry last year and am currently revising a manuscript for submission to a journal. I definitely want to write more children’s books on mental illness. I’ll start my psychiatry residency this summer and am eager for more clinical experience to help guide my writing. I’m envisioning that my future practice will be very holistic, combining psychotherapy techniques with medical management in treating children, adolescents, and their families. I’d love to find room to integrate bibliotherapy, play therapy, and dance therapy. That would be my dream.