By Rachel Martel, a 4th year medical student at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, and a former English major at Tufts University. She plans on pursuing a residency in Ob/Gyn.

If “all the worlds a stage,” then the operating theater is no different. Surgeons of the Renaissance and nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, despite the modern day medical profession’s emphasis on privacy, stoicism, and quiet dignity, were historically required, not only to heal, but to entertain. In an article entitled “Inside the Operating Theater: Early Surgery as Spectacle,” Rebecca Rego Barry writes, “The language used to describe surgical theaters supported this idea that surgery was a performance, with drama, gore, nudity, and death just part of the act…the applause a surgeon received upon entering the theater only heightened the spectacle, complete with rows of ogling observers.”1 This practice of having observers throughout an operation provides a lens through which to examine the layperson’s historical perspective on medical practice. Not only were physicians, medical students, and family members present during the procedure, but artists could be commissioned to immortalize the surgery in a painting. An analysis of these works thus provides not only a glimpse into how surgeons orchestrated their performances, but also insight into the public’s response and expectations of surgeons at the time. And though modern- day ethics generally forbids public observation of medical practice, medicine as spectacle remains alive and well in the form of medical dramas on television, shows which reveal which expectations of the medical profession have persisted into the twenty first century.

In 1632, Rembrandt crafted The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, an oil painting commissioned by the Amsterdam Guild of Surgeons. At the time, public autopsies, held several times per year on the cadavers of deceased convicts for the edification of the medical community and the general public, were raucous affairs. Barry quotes Julie V. Hansen as stating, “…the anatomical theater, which was lit by scented candles to augment the dim light from windows and sometimes featured music played by a flutist…took on a festive and theatrical atmosphere.”1 Yet Rembrandt’s painting, which depicts Dr. Tulp dissecting the left arm of a cadaver while seven other physicians observe the proceedings, has an air of dedicated, epistemological study2. Yes, the columns in the background belie the grand hall in which the event is taking place, and yes, the restless, discordant positioning of the observers intimates the charged atmosphere, but Dr. Tulp himself is the picture of calm. In the light emanating from the arches behind him, Dr. Tulp is glowing and self-assured, unaffected by the tumult that surrounds him. His gaze is steady and clear, his gesticulations are quiet, his clothing is impeccably clean. Thus we see that while the medical profession was expected to put on a show for the public, the audience dually required that the professional identity of the physician not be lost. He was jointly a kind of magician revealing “secrets of nature”1, and a respectable harbinger of scientific fact.

We see this dichotomy—the performer vs. the scientist– repeated in Thomas Eakins’ The Gross Clinic. Painted in 1875, the work displays the surgical amphitheater of Jefferson Medical College, where Dr. Samuel Gross performs surgery on the left thigh of a patient assisted by five other physicians, and observed by the patient’s mother (who looks on in horror) and a cadre of medical students. Again, a protagonist is portrayed who, although clearly a performer, is venerated and respected, standing in a beam of light and commanding a room of onlookers. Yet Eakins’ representation of Gross differs greatly from Rembrandt’s representation of Tulp, perhaps reflecting a societal shift in expectations for physician behavior. Where Tulp is calm, Gross is stormy, with a thunderous cloud of curly hair, rigid limbs, and an expression that is so focused as to almost look angry. There is an unapologetic brashness to the blood on his hand, and the way he takes charge of the space by leaning on the operating table. This change to depicting Gross as stormy could be a result of the shift from performing autopsies on cadavers to performing surgeries on living patients—a societal acceptance of the fact that operations on the living require a level of steely gravitas not needed when merely operating on the dead. Indeed, the painting was recently restored to reflect the darker hues of the original work, 3 hues which project a shadowy grimness and reflect the dangerous nature of surgery. During this time, it makes sense that the public would want physicians who exuded a forceful confidence, and who could convince them that they were in strong (albeit dirty) hands.

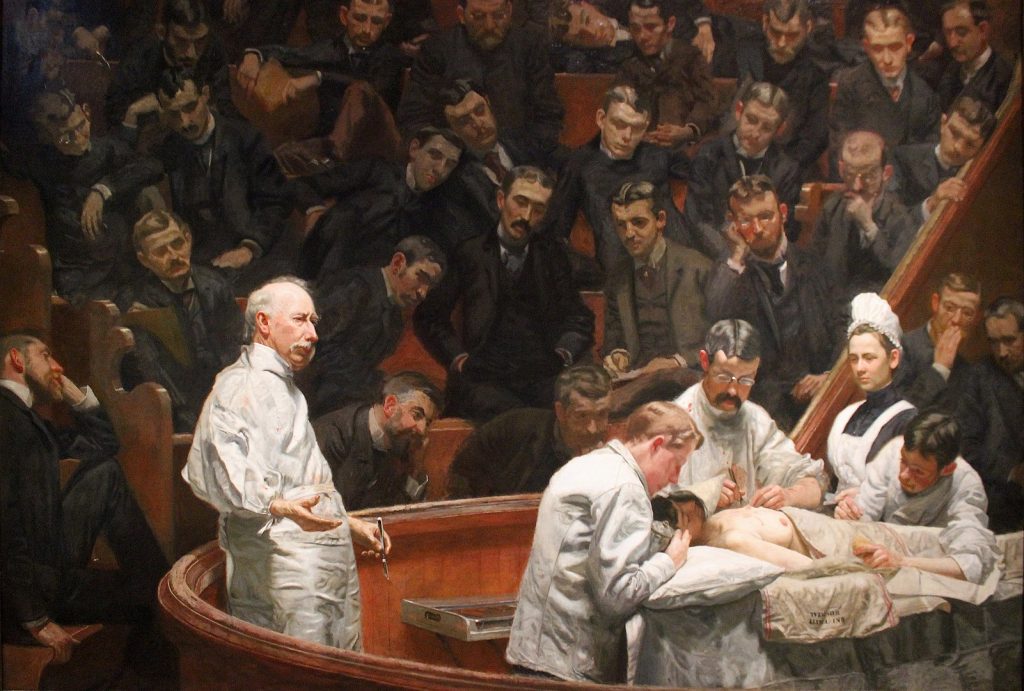

In Eakins’ The Agnew Clinic, painted in 1889 to honor the retirement of Dr. David Hayes Agnew from the University of Pennsylvania, much has changed from the days of Dr. Gross. The amphitheater full of learners remains, but with the coming of germ theory, the surgical table has transformed from one of dim griminess, to one of shining sterility. Dr. Agnew postures in a clean, white surgical coat, holding a gleaming scalpel in his hand. His confident stance provides a contrast to the quizzical expression on his face- he appears to be simultaneously lecturing and also asking a question of his audience. It is notable that despite Agnew’s inquiring glance, which stands in stark contrast to Gross’ look of solemn knowledgeability, the artist depicts him as a bright and solid force within the room. This suggests that the acceptance of germ theory and the subsequent changes in medical practice that it provoked, may also have provoked a shift in the public’s expectations of doctors—that they not only perform their duties adequately, but also question the system continuously. If something so fundamental to the success of surgery as washing your hands had been discounted for so long, what other practices should be questioned and changed? Dr. Agnew’s portrait indicates that the public expected doctors to start answering that question.

Today, popular medical dramas continue to depict physicians in ways that underscore the public’s expectations of the medical field. Grey’s anatomy, a surgical drama that follows a group of surgical residents through their training and beyond, exemplifies not only how laypersons expect physicians to behave, but also what they believe medical science to be capable of. A study published in Trauma Surgery and Acute Care entitled, “Gray’s Anatomy effect: television portrayal of patients with trauma may cultivate unrealistic patient any family expectations after injury,” found that while a greater percentage of patients in the television show died than would be expected in reality, the patients that did survive spent less time in the hospital than would be expected given the severity of their injuries, and were more frequently discharged home rather than to a rehabilitation facility4. 5 Thus, the public has an expectation that doctors heal with finality—that when their work is done and a life has been saved, the person who has been miraculously cured will return to their old life, as good as new. And a Daily News article states that on the TV show, “Each patient and each case…were treated with the dignity, attention, respect, and kindness, that most real people walking into hospitals across the country can only dream of.”5 This underscores the value that the public places on bedside manner, and on being treated as an individual within the healthcare system, and not as simply one patient of many.

House M.D., is a medical drama that focuses not on a surgeon, but on an internist double boarded in infectious disease and nephrology, who is known for solving medical mysteries. Each episode follows a familiar structure: a victim falls ill with a mysterious illness, many solutions are posited and all are proved wrong, and then, at the last second, just as the patient is about to succumb to death, Dr. House steps in with a life-saving diagnosis. The show reflects the public’s expectation that the medical profession will always have an answer, and that this answer will arrive quickly. In an NBC article entitled “House effect: TV doc has real impact on care,” a nurse is quoted as stating, “While House makes a diagnosis and, in most cases, cures that patient all within the span of one hour-long episode, in reality it takes an average of seven years to diagnose a rare disease.”5 Amid an increasingly information dense world, in which the internet provides answers within seconds and libraries worth of information are constantly at our fingertips, it can be difficult to accept uncertainty, especially when lives are at stake. House provides a comforting sense that every question has an answer, every symptom a physiologic root, and every disease a cure.

Throughout history, medical practice has been observed and replicated by those outside of the profession. Whether these representations are in paint or on screen, they provide evidence that as society has changed, so too have expectations of what the medical profession can provide, and how medical professionals should behave. As we have advanced from Renaissance autopsies, to the acceptance of Germ theory, to the technological successes of today, the expectation of what the physician is has progressed from competent professional, to forward-thinker, to medical miracle worker. Like surgeons of the past, modern medicine requires balancing performance and reality, a delicate tightrope that must be walked with care.

References

1. Barry, Rebecca Rego. “Inside the Operating Theater: Early Surgery as Spectacle .” JSTOR, 9 Dec. 2015, daily.jstor.org/inside-the-operating-theater-surgery-as-spectacle/.

2. Noë, Alva. “An Intersection Of Science And Art In Rembrandt’s ‘Anatomy Lesson’.” NPR, NPR, 29 May 2015, www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2015/05/29/410488508/an-intersection-of-science-and-art-in-rembrandts-anatomy-lesson.

3. Rose, Joel. “Eakins’ Classic ‘Gross Clinic’ Gets Another Look.” NPR, NPR, 25 July 2010, www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=128721065.

4. Serrone, R. O., Weinberg, J. A., Goslar, P. W., Wilkinson, E. P., Thompson, T. M., Dameworth, J. L., … & Petersen, S. R. (2018). Grey’s Anatomy effect: television portrayal of patients with trauma may cultivate unrealistic patient and family expectations after injury. Trauma surgery & acute care open, 3(1), e000137.

5 Scotti, Ariel. “’Grey’s Anatomy’ Blamed for ‘False Expectations’ of Medical Care .” Nydailynews.com, New York Daily News, 7 Apr. 2018, www.nydailynews.com/life-style/grey-anatomy-blamed-false-expectations-medical-care-article-1.3833799.

6. Scotti, Ariel. “’Grey’s Anatomy’ Blamed for ‘False Expectations’ of Medical Care .” Nydailynews.com, New York Daily News, 7 Apr. 2018, www.nydailynews.com/life-style/grey-anatomy-blamed-false-expectations-medical-care-article-1.3833799.