By Gabriel Redel-Traub

There is something eerie about walking into the Folk Art Museum’s posthumous portraiture exhibit. The last line of the introductory panel to the exhibit reads: “We cannot help but hear them whisper ‘remember me.’” This sentiment rings true.

The exhibit is split into three rooms and filled with portraits of apparently posthumous subjects. I say apparently, because to a 21st century viewer, nothing in these portraits would indicate that the subjects were dead at the time they were painted. Informative panels, however, inform us that there are visual clues, motifs, and allusions in each portrait which would suggest to a 19th century viewer that the subject had passed away prior to the portrait being painted. This explains why many of the portraits have subjects with only one shoe on and why there are cats in many of the pieces.

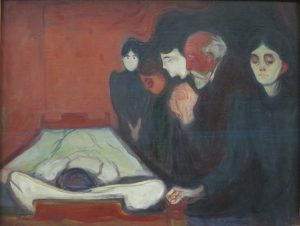

The large majority of the pieces on display in the exhibit are simple portraits. The onlooker is directly confronted by the subject. In this way, these folk-art portraits differ drastically from the canonical depictions of death in the works of our greatest artists. In these works, death is taken as an opportunity to grapple with life, futility and grief: Michaelangelo’s Pieta and Edvard Munch’s By the Deathbed come to mind.

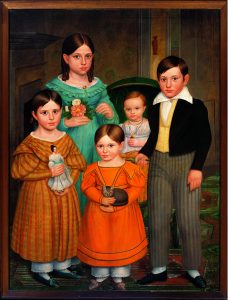

The simple mimetic nature of these folk-art portraits, on the other hand, is in part explained by their purpose. Many of the portraits on display in the exhibit were originally meant to hang in the home of the family of the deceased, a visual representation of a lost loved one serving the purpose a photo would today. As such, the portraits show their subjects as what they are not, vivacious: children play with dolls, a young girl picks flowers, a young boy fishes in a lake.

In stark contrast to the paintings’ vivacity, the exhibit also includes 80 daguerreotypes with haunting black and white images of dead adults, or parents with bleak expressions staring out at you, their dead children strewn across their laps. The images arranged together in a small room of the exhibit force the viewer into a direct confrontation with the dead and are particularly haunting.

And yet, still, even though most of the portraits don’t show explicitly posthumous subjects, there remains an eerie feeling throughout the exhibit. Some part of that strangeness can be explained by the fact that the artists of many of the pieces in the exhibit were untrained giving their work a medieval feel- namely, the tendency to paint strangely adult faces on young children

However, the greater contributing factor, I think, is the mere knowledge that each portrait- and most of the portraits are of children- was made posthumously. This forces uncomfortable questions: was the deceased arranged as a model to be painted from? Or was the subject drawn from memory? How exactly did this process work? The information provided by the museum only partially answers these questions.

The exhibit forces the modern onlooker into an empathic interaction with the deceased and with the story that the onlooker creates. In one particularly haunting piece The Farwell Children, five children look on demanding you take them in. Did all five of these young children die? Where did they come from? Where are the mother and father and how could they possibly endure this? The exhibit thrusts us into a more intimate conversation with death; one which our ancestors- for whom death was constantly looming more ominously over- were often preemptively forced into.

In the 21st century, the overwhelming attitude towards death is to push it away-out of sight, out of mind. This is, frighteningly, true for medical professionals and students studying medicine. The D word is taboo, everything a doctor is fighting against, so why should it even be brought up? And yet, death is also an invariable part of a medical student’s experience. As Laura Ferguson, artist-in-residence at NYU School of Medicine writes:

“For most medical students today, the dissection of a cadaver represents their first confrontation with death, and with the visceral reality of the human body. They come to the experience with great curiosity but also with a degree of discomfort, even fear, about what they may encounter. They bring a sense of empathy and caring to their relationships with these “first patients” – but because it requires cutting, this rite of passage is their first experience of having to “hurt to heal.” So, for many students, their time in the Anatomy Lab begins a process of emotional detachment.”

Looking at the posthumous portraits- and at art more generally- serves as a way to reconnect, to reestablish the humanity and individuality of the deceased. It obliges us to find beauty in death and to acknowledge that death is an intimate part of life.

Securing the Shadow: Posthumous Portraiture in America is on at the American Folk Art Museum through February 26th

Gabriel Redel-Traub is a 1st year medical student at NYU School of Medicine and a Rudin Fellow for 2016-2017.

* The Farwell Children Deacon Robert Peckham (1785–1877)

Fitchburg, Massachusetts c. 1841

Oil on canvas 53 1/2 x 40 1/2″; 62 1/2 x 48″ (framed)

Collection American Folk Art Museum, New York

Gift of Ralph Esmerian, 2005.8.11

Photo © 2000 John Bigelow Taylor

* Baby in Blue William Matthew Prior (1806–1873)

New England c. 1845 Oil on paper on wood 23 3/4 x 17″; 29 3/8 x 22 5/8 x 1 1/4″ (framed)

Collection National Gallery of Art, Washington Gift of Edgar William and Bernice Chrysler Garbisch, 1953.5.58 Photo courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington