Commentary by Thomas Lawrence Long, Associate Professor-in-Residence, School of Nursing, University of Connecticut

Commentary by Thomas Lawrence Long, Associate Professor-in-Residence, School of Nursing, University of Connecticut

Name three popular physician writers working today.

Atul Gawande. Pauline Chen. Oliver Sacks. Jill Bolte Taylor. Jerome Groopman. Rafael Campo. Deepak Chopra. Edward de Bono. Andrew Weil.

Well, that was easy.

Now name three physician authors who are part of the Western literary canon.

Hippocrates. Galen. The author of the Gospel According to Luke and of Acts of the Apostles. Hildegard of Bingen. Charles Eastman. Arthur Conan Doyle. Anton Chekhov. William Carlos Williams. Oliver Goldsmith. Thomas Browne. John Polidori. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. Lewis Thomas. Thomas Bowdler (unfortunately).

An embarrassment of riches. That was easier still.

Now name three nurse authors, who are either writing today or are part of the literary canon.

All right, I’ll give you twenty-four hours to get back to me.

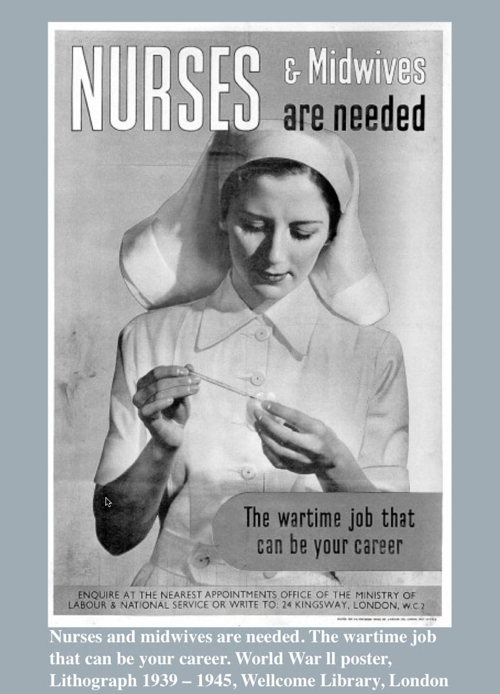

Where Are the Nurse Writers?

Paradoxically, the healthcare professional field established by a prolific Victorian English author, Florence Nightingale (whose 1859 Notes on Nursing: What Nursing Is, What Nursing is Not has never gone out of print), finds few of its writers on the tips of our tongues. And even at the origins of professional nursing in the United States during the Civil War, one of America’s most beloved authors, Louisa May Alcott, started her literary career with Hospital Sketches, an account of her experiences as a nurse in a military hospital.

Why are there so few well known nurse authors? And what nurse writers are ready to be discovered by a larger audience?

When I have asked nurse editors and scholars the first question, the answers have centered on two points. First, nursing has often been viewed (and until recently nurses viewed themselves) as ancillary, literally ancilla, handmaiden, a feminized, subservient profession deferring to the physician. Not only was the nurse not expected to have insights into the human condition; she (and the nurse usually was female) did not have the “room of one’s own” to enable reflection and literary productivity. The physician had his (and the physician usually was a man) office as a retreat, while nurses just had . . . the nurses station–a public location at the hub of medical care and utterly lacking in privacy or solitude.

Second, nurses often were not educated for their profession in the tradition of the liberal arts and sciences. Instead they were frequently trained in hospital nursing programs, or since the second half of the twentieth century at community colleges in two-year associate of science degree programs. Baccalaureate programs in nursing have been a feature of the nursing curriculum since earlier in the twentieth century, but many nurses even today are not the products of that broadly general education.

Nursing Writing

Nurses seem uniquely equipped, however, to comprehend the whole person of the patient, spending considerably more time with the sick than physicians do and aware of the entire psychological, social, and spiritual inflections of their patients. Nurses have historically been encouraged to keep journals and diaries of their clinical experiences, so the raw material for memoir is in fact at hand. As Jane E. Schultz observes of the contrast between clinical accounts by Civil War military physicians and those by their nurses:

Though nurses’ styles of self-expression differed widely, they wrote about their patients with a singular degree of material specificity, and they resisted surgeons’ tendency to blur patients’ individual characteristics. In their letters and diaries, they referred to patients by name, frequently mentioning hometowns, culinary tastes, or other distinguishing details. Often they quoted their conversations with soldiers, which surgeons who kept diaries rarely did. . . Surgeons’ diaries do not show nearly the same individualization of suffering. They were more likely to refer to their patients in the abstract or to refer to the clinical details of a particular treatment without mentioning the soldier’s name at all. (378-379)Civil War nurse diaries are among the more vivid and moving accounts of the war, whether from the hand of the domestic Louisa May Alcott, or the sensationalist S. Emma E. Edmonds, author of the memoir Nurse and Spy in the Union Army. Moreover, feminist critic and literary scholar Elaine Showalter in an introduction to Florence Nightingale has characterized Nightingale as a major literary figure in English feminism, bridging Mary Wollstonecraft in the eighteenth century and Virginia Woolf in the twentieth.

Who are Nightingale’s literary descendants working today? They are men and women, and they are many. They are working in a variety of genres, and their work has earned frequent anthologizing. Cortney Davis and Judy Schaefer’s two collections, Between the Heartbeats: Poetry and Prose by Nurses (1995) and Intensive Care: More Poetry and Prose by Nurses (2003), have brought nurse writers to a wider audience. Schaefer’s more recent anthology, The Poetry of Nursing: Poems and Commentaries of Leading Nurse-Poets, gives 15 nurse poets the space to present and to comment on three or four of their own poems, an unusual and engaging meta-analysis. An accomplished poet, Davis is also a talented essayist, whose recently published The Heart’s Truth: Essays on the Art of Nursing encapsulates the relationship between clinical practice and writing:

. . . I find that when I’m not seeing patients, it’s a struggle for me to write. It seems that for me, nursing and writing have become, over the years, inextricably bound. That intimate connection that links us, human to human, is essential both to my vocation and my avocation. (98)Writers like Davis and Schaefer, Jeanne Bryner, Theodore Deppe, Veneta Masson, have published their work in distinguished literary journals, such as Minnesota Review, Prairie Schooner, Hudson Review, Poetry, The Sun, and Kenyon Review, as well as in their own books published by respected presses.

These nurse writers join an eclectic canon. Katherine Prescott Wormeley (1830-1908), an American nurse in the Civil War, was a highly respected literary translator, who turned works by Balzac, Daudet, and Dumas to English. Sarah Chauncey Woolsey (1835-1905), an American children’s author and editor, wrote under the pen name Susan Coolidge. Lillian D. Wald (1867–1940) was a community health activist and author of two memoirs, The House on Henry Street (1911) and Windows on Henry Street (1934). Ellen LaMotte (1873-1961) published several books, including travel and wartime nursing narratives. In addition, today nurse scholars publish their research in over 100 journals of nursing science and professional practice.

Florence Nightingale, whose collected works now runs to thirteen volumes in the edition published by the Canadian University of Guelph’s Wilfrid Laurier University Press, put pen to paper in the service of a variety causes, not all of them related to health care. As Lytton Strachey observes in his profile of her in Eminent Victorians, Nightingale’s dedication to spirituality led her to write a tract on the spiritual wellbeing of working-class artisans:

Then, suddenly, in the very midst of the ramifying generalities of her metaphysical disquisitions there is an unexpected turn, and the reader is plunged all at once into something particular, something personal, something impregnated with intense experience—a virulent invective upon the position of women in the upper ranks of society. Forgetful alike of her high argument and of the artisans, [she] rails through a hundred pages of close print at the falsities of family life, the ineptitudes of marriage, the emptinesses of convention, in the spirit of an Ibsen or a Samuel Butler. Her fierce pen, shaking with intimate anger, depicts in biting sentences the fearful fate of an unmarried girl in a wealthy household. It is a cri du cœur . . .The best of nursing writing shares this passion, a thirst for justice, an advocacy of vulnerable populations. Nightingale did not suffer fools gladly, and her view of the role of nurses went well beyond the ancillary, for as she wrote, “No man, not even a doctor, ever gives any other definition of what a nurse should be than this — ‘devoted and obedient.’ This definition would do just as well for a porter. It might even do for a horse. It would not do for a policeman.”

Works Cited

Alcott, Louisa May. Hospital Sketches. Boston: J. Redpath, 1863.

Davis, Cortney. The Heart’s Truth: Essays on the Art of Nursing. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2009.

Davis, Cortney, and Judy Schaefer, eds. Between the Heartbeats: Poetry and Prose by Nurses. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1995.

—. Intensive Care: More Poetry and Prose by Nurses. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2003.

Edmonds, S. Emma E. Nurse and Spy in the Union Army. Hartford, CT: W. S. Williams & Co., 1865.

Nightingale, Florence. Notes on Nursing: What Nursing Is, What Nursing is Not. London: Duckworth, 1859.

Schaefer, Judy, ed. The Poetry of Nursing: Poems and Commentaries of Leading Nurse-Poets. Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 2006.

Schultz, Jane E. “The Inhospitable Hospital: Gender and Professionalism in Civil War Medicine.” Signs, 17.2 (Winter, 1992), pp. 363-392.

Showalter, Elaine. “Florence Nightingale.” Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar. The Norton Anthology of Literature by Women: The Traditions in English. New York: W.W. Norton, 1996. 836-837.

Strachey, Lytton. Eminent Victorians. New York: Putnam, 1918. Retrieved from http://www.bartleby.com/189/204.html

Wald, Lillian D. The House on Henry Street. New York: Holt, 1915.

—. Windows on Henry Street. Boston: Little, Brown, 1934.