Guy Glass, MD, MFA, Clinical Assistant Professor

Center for Medical Humanities, Compassionate Care and Bioethics

Stony Brook School of Medicine

I am a psychiatrist who writes plays and has several professional productions and published plays to my credit. Having recently earned an MFA in theater from Stony Brook University, I am now affiliated with the Center for Medical Humanities, Compassionate Care and Bioethics at Stony Brook University School of Medicine. At both Stony Brook, and starting this fall at Drexel, I teach an elective entitled “Theater and the Experience of Illness” in which medical students both read plays and write their own dramatic monologues.

I dedicated my master’s thesis to finding ways that plays might be used in medical education. This involved creating dramatic adaptations of two of Chekhov’s “doctor” short stories, including “A Doctor’s Visit.” In April 2016, I was invited to bring “A Doctor’s Visit” to the Arts and Health Humanities Conference in Cleveland. There, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to create a piece of theater with five medical students who happen to be very fine actors and who contributed the blog post below. I’m delighted to see that the exercise gave the students insight into what the arts can contribute to medical training. Moving forward, I hope to find other institutions that will allow me to bring this program to their students.

Reflections on the Importance of Dramatic Arts in Medical School Curricula

Alicia Stallings, DaShawn Hickman, and Nick Szoko

As a part of the Medical Humanities conference held at the Cleveland Clinic on April 9th, 2016, we were asked to perform a dramatic reading of an adapted short story by Anton Chekhov entitled, “A Doctor’s Visit.” The piece, thoughtfully developed by Guy Glass, MD, MFA, takes place in a factory town outside of Moscow in the 1890s. It features a diverse group of characters: Dr. Korolyov, a middle-aged physician working to jumpstart his struggling practice; Boris, his eager apprentice; Christina Dmitryevna, a caricaturized spinster; Liza, a seemingly spoiled heiress; and Madame Lyalikov, Liza’s frenetic and overbearing mother. The story centers on the encounter between Dr. Korolyov/Boris and the inhabitants of the Lyalikov mansion. Dr. Korolyov is called upon to tend to the needs of Liza. Motivated by the prospect of compensation, Dr. Korolyov and Boris make their way to a gritty industrial town outside of Moscow where the gaudy mansion is situated. They arrive to find a hysterical young woman, Liza, nearly bed-bound for no apparent reason. Initially, Dr. Korolyov operates in a detached, business-like manner when examining and interacting with Liza. He is eager to perform his duties and exit, having excluded any true disease process; however, when Madame Lyalikov invites Korolyov and Boris to spend the night at the mansion, Dr. Korolyov achieves a moment of profound insight when he stands in the property’s garden and gazes at the glowing factory lights beyond. In this setting, Korolyov recognizes his lack of compassion and revisits Liza in her room, finally able to connect with the young woman and “cure” her by acknowledging and validating her unique narrative. In reading, rehearsing, and performing this work, we extracted three important themes: empathy, justice, and professionalism.

Justice, as told from the perspective of Boris (DaShawn)

Justice, as told from the perspective of Boris (DaShawn)

Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine

At the start of the play, Boris attempts to wake the doctor, but we quickly learn that Korolyov would rather the student learn more of the basic science and medicine on his own. He is told to “memorize all the books on my bookshelf, dissect all the rats and frogs you can find. And come back at noon.” As outrageous as this sounds coming from the doctor, many schools have taken to this self-directed learning style. Students are spending more time reading and learning on their own or in groups than with professors during their first two years of medical school. The play also makes it abundantly clear that although students need patients to learn from, patients are not always as willing to allow students to learn from them. One of the characters in the play, Christina Dmitryevna, bans Boris from seeing the patient with his teacher. She expresses how she is displeased to be “running a medical school.” Being able to act in this role allowed me appreciate all the time I am able to spend with patients during my formative years as a student doctor.

Although the doctor doesn’t appear interested in directly teaching Boris basic sciences, he does take the time to teach him about communication skills, history, and society, all topics that will have an impact on the quality of doctor that Boris will become. A theme that emerges from interactions between Dr. Korolyov and Boris is justice. As the doctor and Boris travel away from Moscow to the industrial town, the socioeconomic disparities become more pronounced. The doctor teaches Boris how poor and hard-working the factory workers are. He tells Boris that even though they are poor like the factory workers, because they are doctors, and thus in a higher social class, “[the factory workers] will always hate us.”

The town is covered in soot from the factory, and so many people have health problems, including the limited life expectancy of 35. Despite this, the doctor lectures, “it is a pampered rich girl we have been asked to care for.” Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. summed up his teachings nicely when he stated “Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health care is the most shocking and inhumane.” The doctor not only points these injustices out to the student but challenges them in front of the student. He asks about the well-being of the factory workers and implies that it is subpar to the wealthy he has come to visit. These are bold actions that not only teach Boris to recognize injustices but to confront and work to dismantle them.

Without future doctors being taught these lessons the injustices that exist today will continue to permeate our healthcare system, stifling advancements in this realm for the betterment of mankind overall.

Professionalism, as told from the perspective of Madame Lyalikov (Alicia)

Professionalism, as told from the perspective of Madame Lyalikov (Alicia)

Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine

In the reading, I portrayed Madame Lyalikov, the mother of the patient in the play. In this role, I found that many principles of professionalism were highlighted during the preparation and enactment of the dramatic reading. One component that stands out was the principle of responsibility to colleagues. During my preparation for the role, it gradually became clear to me how different I was from the character. I could not relate to her in her stage of life (I am not a mother), nor her walk of life (I am not wealthy), nor her personality/disposition (I am neither of the anxious variety nor passive). Yet, despite my lack of similarity to this character, for the sake of the audience, to learn from the play, and for the sake of my fellow student-actors, so that they could also portray their characters well, I needed to work to understand this character—her perspective and her mindset―to meet my responsibility to the group.

Principles of professionalism specific to the practice of medicine were also highlighted in the play. Most notably, the issue of bias was an important theme, which was illustrated by Dr. Korolyov’s negative comments to the student about the patient and her mother. In my role as Madame Lyalkiov, I had an interesting vantage point, being both privy to Dr. Korolyov’s bias, as an actor, as well as the object of his prejudice, as the character. In this unique position, I found myself reflecting: is Korolyov aware of his prejudice towards her and her daughter? Can she feel how he feels about them? Does she feel that his prejudice is impacting his care of her daughter? Is his prejudice hurtful to her? It was very interesting to reflect on these questions from the vantage point of a future healthcare professional. One likes to think that her attitude towards others can be isolated from how she treats them, and that one can even hide their prejudice, so that the other party is not aware. However, is this true? Are we as medical professionals, and as people in society at large, able to separate how we feel about others from how we treat them? And perhaps more importantly, if how we feel about them is based in prejudice (as in the case of Dr. Korolyov), is it acceptable to continue to harbor these biases, even if we think we can separate them from how we treat patients? These are important questions for students to consider as move forward in their development as medical professionals. My role as Madame Lyalikov brought these questions to the forefront, and gave me much to reflect on with regards to professionalism in interacting with and caring for patients.

Empathy, as told from the perspective of Dr. Korolyov (Nick)

Empathy, as told from the perspective of Dr. Korolyov (Nick)

Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine

“You will learn, if you are to be a doctor, you do not always have to do a thing.” As Dr. Korolyov prepares to depart from his visit at the lavish Lyalikov mansion, he offers these reflections to his young assistant, Boris. As medical students, the words of Dr. Korolyov surely resonate with us. We embrace ignorance, thrive in discomfort, and accept inaction. We feel dually limited and protected by our positions as trainees. We are told that the greatest gifts we can give our patients are not medical expertise or surgical acumen, but rather our time, humility, and empathy. So what happens when these fail?

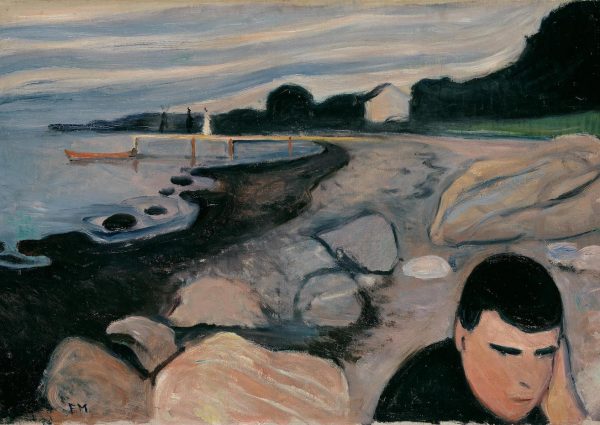

It is no secret that the ability of medical professionals to empathize declines over time. We are cautioned from the first day of medical school regarding this well-cited trend. When we examine Korolyov, we see the familiar vices of the burned out physician. His initial motivation to visit the Lyalikovs is financial. He forms a prejudgement of his patient based on socioeconomic class and lets this guide his diagnostics. There is an unspoken aroma of efficiency and industriousness that hovers over the encounter. As medical students, we face a similar climate. Our attitude towards learning and career choice is tinted by the haze of student debt. We train in tertiary care centers that venerate evidence-based medicine and cost-conscious care. We aim for concision and efficiency in our interviews and presentations. Amidst this, we strive to temper our own arrogance so as not to become hardened to the pain of those around us. With each day we spend on the wards, we are tempted to limit our vulnerability and minimize our emotional presence so as not to compound physical exhaustion with psychological. We ask ourselves, “Am I becoming a professional?” or, “Am I losing my humanity?” We become less of Boris and more of Korolyov.

For Korolyov, it takes a revelation, an “Aha!” moment to arrive at the proper diagnosis. Indeed, it is not until his liminal experience in the garden that Korolyov finally overcomes his psychological barriers to connect with his patient, recognize his biases, and act as a healer. Romanticizing such transformative moments is not unfamiliar in our profession. Our attendings often recall patient encounters that made them stop, reflect, and even reform. As medical students, we remember our first patient death, the first child we delivered, or our first “thank you.” These moments, though rare, do more than just provide subtext for television dramas or ignition for research funding campaigns. In some ways, these instances and the act of recounting them eternally bind us to the humanism of our craft while allowing us to mature in our profession. Storytelling, whether it by play, article, or interview, remains powerful, not only for those who listen, but also for those who share. In reliving these experiences, we evoke our emotional self, and this is often done from a place of greater experience and wisdom. The value of this exercise cannot be understated, because beyond connecting us to the ethereal concept of “emotion,” it allows us to reflect, critically and honestly, about how this experience and others like it have shaped our practice today. By participating in a dramatic reading of “A Doctor’s Visit,” I told a story that, over time, became my own. This opportunity offered a space for vulnerability and introspection, and I am thankful that I could engage in this dialogue alongside my colleagues.

Conclusions

For many students entering medical school, it has likely been years since they have taken part in a traditional stage play. Although many may have participated in variety shows or other short dramatic works in college, these dramatic engagements are notably different from traditional plays. The content of variety shows is written by the students themselves, and therefore generally presents contemporary issues from contemporary lens using contemporary language (most of which are shared by and native to the students). Other works of drama present the opportunity to explore diverse settings, subject matter, and perspectives. Utilization of selected plays and short scripts as teaching tools for individual students as well as groups of students has great potential. Indeed, for many medical students, there is great power in silencing our own voice to fully walk in the shoes of another and experiencing the world from their eyes. Script readings can offer students an opportunity to do so again, while providing a reminder why it is important to do so in life as well.

Other members include:

Anne Runkle and Megan Morisada, Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine.