Fauci co-director John Hoffman discusses the documentary with students in the NYU SOM Medical Humanities elective

Introduction:

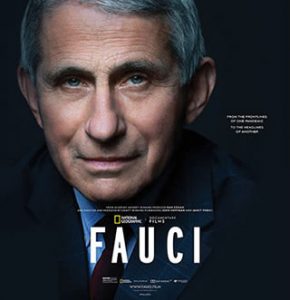

In February 2022, students enrolled in the Medical Humanities elective at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, met with John Hoffman to discuss Fauci, a 2021 documentary he co-directed with Janet Tobias on the life and work of Dr. Anthony Fauci. A physician-scientist whose decades-long career at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease has spanned every major infectious outbreak since HIV, Dr. Fauci has played an important role in guiding health policy and response in the United States. The students spoke at length with John about his inspiration for the film, the research and editing process, and themes of and lessons from a life in service to the health of America.

In February 2022, students enrolled in the Medical Humanities elective at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine, met with John Hoffman to discuss Fauci, a 2021 documentary he co-directed with Janet Tobias on the life and work of Dr. Anthony Fauci. A physician-scientist whose decades-long career at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease has spanned every major infectious outbreak since HIV, Dr. Fauci has played an important role in guiding health policy and response in the United States. The students spoke at length with John about his inspiration for the film, the research and editing process, and themes of and lessons from a life in service to the health of America.

This week of the elective focused on Physicians as Partners in Social Change. The course leaders were Lucy Bruell, MS (LB), and Dr. Steven Field (SF).

Student interviewers: Joshua Jiang (JJ), Akbar Salman (AS), and Ellen Yin (EY)

Student interviewers: Joshua Jiang (JJ), Akbar Salman (AS), and Ellen Yin (EY)

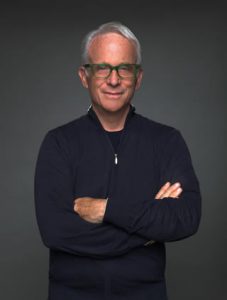

John Hoffman bio:

John Hoffman is an Emmy award winning director with a special focus on health-related issues. This is his sixth project in partnership with the National Institutes of Health.

The interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

LB: Thank you, John, for joining our seminar today. Let’s begin with asking the students for their initial reactions to the film.

EY: What struck me the most, especially as a younger person who did not live through the AIDS crisis, is how little I knew about what that really was like. I try to keep up to date with the news, but after having watched this documentary, I realize there are through lines here that are very easily forgotten. Our cultural memory seems quite short, particularly when it comes to how important some of these people are.

I was also very struck by Dr. Fauci’s willingness to reach his hand out [to AIDS activists] and say, I understand where your feelings are coming from, and I want to hear your perspectives. That’s something that is not as common as it should be.

JH: That’s one of the reasons that the film was made, because we the filmmakers knew that story. and the relevance that it had today. How do you tell that story? How do you draw those parallels [between the Covid-19 pandemic and the AIDS epidemic]?

The process of editing creates opportunities that you could never really imagine. Not until you put two scenes next to each other do you find some other kinds of meaning that can only be discovered when they’re next to each other. So, one of the most interesting aspects of making the film was how we went back and forth in time to compare the reaction to these two pandemics of our time.

Beginnings of the Fauci Project

LB: When did you start filming? Was it as COVID was developing? What did you set out to do initially?

JH: Janet Tobias, my co-director, had been speaking with Dr. Fauci about making a biography of him before COVID. She and I hardly knew each other, and I had nothing to do with that [project]. Dr. Fauci and his wife are both in a series I did about the clinical research center at the NIH building 10, which is the largest hospital in the world solely devoted to research. I had done a six-hour film that is set in that building. Dr. Fauci and Dr. Grady are both in it so I had that relationship.

When COVID began, and it was really emerging in the news in January and February [2020], I reached out to the leadership of the NIH, Dr. Collins’ office and said I would love to do a film about Dr. Fauci, follow him during this time, and tell his story. They were very excited and said, “Do you know Janet Tobias?” I said yes, and we immediately teamed up. Lockdown was March 13th, and we started shooting in April.

Researching Fauci and Developing a Story in Real-Time

LB: The story changed from your original idea and became broader. And you have a very interesting structure because it’s not chronological. Some documentaries go from one point to the next. How did you come up with that? I thought it was one of the strengths in the movie.

JH: Thank you. We did a tremendous amount of research. We had a very good research team for the topics that we were dealing with. And those were not only Dr. Fauci, his entire life and biography, but also all the major public health events of his career. So, we were doing deep dives into Ebola and SARS and MERS and all those things. We had a remarkable archive team as well. We gathered thousands of clips not only of Dr. Fauci, but anything in the news archives of any of those events.

On paper, we were working chronologically to make sure that we were being as thorough as possible. Documentary films, in many ways, are a collection of scenes. Important meaning can be found in how you put things together. In the earliest days, we were working on sections of Dr. Fauci’s life. Our task then became, okay, we don’t want to tell this chronologically, there’s no innovation there. So, what are the themes that are emerging when talking about the events of Dr. Fauci’s life? It’s the role of activists, and how Dr. Fauci is responding to those who are speaking out against him. He is now serving his eighth president. So, what are the conditions of different presidencies, the kinds of people that he’s engaging with, the composition of the Hill? Those became points where we could move back and forth in time because of a particular equivalence or contradiction in terms of how he was being received as a public health official. There was no grand plan that mapped out the way you see [the film]. It was a continual process of discovery.

As important as it was for us to collect the historical archive, we were also amassing the unfolding archives. Dr. Fauci was constantly appearing, we’re trying to get every one of those into our archives. There are events unfolding on the Hill and scientific announcements where Dr. Fauci isn’t there, but you want to have them at your disposal.

Much more to the point is the unfolding narrative of this conflict that emerged, when Dr. Fauci first steps up to the podium and contradicts the president. The Fauci narrative took a dramatic turn at that point. He becomes—these are my words—a tool for distraction by the right. Up until that point, he had been appearing on Fox as an expert. You see that in the film. And then the narrative shifts. But what was interesting is, we started making the film in April of 2020. The last time I interviewed Dr. Fauci was in June 2021. So, this is over a year later. It was interesting to go through the experience of interviewing him through the election, the swearing-in of Biden, and in those months to feel how certain things you thought were the most important thing in the world nine months earlier, and now, there was no place for them in the film. There were things that I had interviewed him about in December of 2020, with great detail, that just would not stand the test of time.

LB: Can you give an example of that?

JH: You see that we talked about hydroxychloroquine. That remained. But there were so many ways in which Fauci was being attacked, or so many ways in which the President was putting out information that some people would say is false and misleading and confusing and dangerous. But you didn’t need to detail them all. Hydroxychloroquine worked as a representation of Fauci having to stand up and say, we don’t have the evidence to support that. It characterized the fundamentally different ways in which these two people understood the role of public health. We didn’t need to expand on any other example of that.

JJ: It sounds like in the process of making this film you were continually reevaluating what needed to go in, what stories needed to be told, and how to line these things up. How did you decide who to interview especially as the story was unfolding and changing before you?

JH: From a filmmaking approach, it was very important to have firsthand historians, people who have worked with and been in the company of Fauci as opposed to writers and journalists. [The latter] have tremendous understanding and knowledge, but they’re second-hand historians. We were successful in finding people who were all firsthand. If they were reporters, they were reporters like Laurie Garrett, who had repeatedly interviewed Fauci over the years, starting with HIV.

It really was the question of looking at the span of his life, people who could speak to his earliest days. You see a brief appearance of somebody who was in his NIH class, 1965. It was very important to have people from different administrations there and to have President Bush there. We wanted people who could speak to important moments in history, with firsthand experience of handling something like the Ebola crisis. The historians for the AIDS crisis—we’re so fortunate that the people that you see who were storming the NIH are still alive, and the therapies saved them. They were able to tell the stories of what they went through. There’s a story behind every single person, and there are many more people that we interviewed who are not in the film. We were going after people who could speak passionately about their experience of working with Dr. Fauci or going against him.

Lasting Effect: Lessons from Fauci and the HIV Epidemic

LB: I’m curious to ask you, Ellen, Akbar, and Josh, how much did you learn about the AIDS crisis from the film that you didn’t know already?

JJ: I was fortunate to take a class on the history of science in the United States in college, and as part of our readings, we read And The Band Played On by Randy Shilts. I think the book is criticized for not exactly painting the most objective picture of the AIDS crisis, but I was exposed to the controversies between the gay community and what they perceived as slowness on the part of the NIH. But seeing that personified and having people talk about their experiences and hearing about their desires for the NIH to move faster, was really fascinating, especially given the contrast to what we’re seeing nowadays, where one of the main criticisms of NIH with the vaccine is that they moved way too fast. With a name like Warp Speed, it just it sounds very different from the NIH of the HIV era.

JH: What’s also different is that the nature of the viruses is just so fundamentally different. The scientific challenges just can’t be compared. There was no scientific base of knowledge to go on for HIV, let alone in identifying it.

SF: Right. They are very fundamentally different. We hadn’t really seen a virus like HIV before. Coronaviruses have been around for a long time. But another fundamental difference is people think that the NIH moved too slowly in terms of medications, too quickly in terms of vaccines. In the popular conception there’s a very big difference. People take medicine because they’re sick and they want to get better. A vaccine is often conceived of as a foreign protein that you’re putting into a healthy body. The fundamental nature of the intervention we’re talking about is very different in the popular mind, certainly.

LB: And then again, the political environment was so different. When AIDS surfaced there was such stigma attached to who got it, and why should research be put toward a disease that mostly was gotten by people who were gay? There was that scene in the Donahue show segment where the woman stands up and asks why are you putting money into AIDS when there are so many other diseases.

JH: I think that’s where Dr. Fauci’s moral fiber comes through. It was not something he discovered in HIV. It was tested in HIV, but he did not find it there. I hope that came through. I have this privilege of having watched thousands of clips, and there are so many examples of that. We could only show a handful to make the point. But his visceral detestation of any sort of inherent bias against others was evident over and over again.

LB: I think you did a wonderful job showing his compassion. There was the scene where the patient who greeted him every morning and then one day didn’t recognize him [due to cytomegalovirus retinitis]. I thought about that interview [of Dr. Fauci], because you asked the follow-up question: “I see that you are still affected.” And he answered, “PTSD.”

That’s the thing about documentary. You pick up on the cues that you encounter during interviews and are able to go further into the story by paying attention to them. I think that’s true in medicine, too. As you interview patients and learn more about them, it’s not simply a checklist of questions that you have.

JH: I’m curious to hear the doctors talk about that. It is something that I’ve come to learn, and only experience has taught me to not be afraid to go deeper when someone’s emotional. However it is that we’re conditioned to retreat at that moment and try to make the person feel better and stop it, the nature of my work has taught me to go further. With Dr. Fauci, and similarly in other films that I’ve made, people are fine with it. In some instances, they’re happy you’ve gone there because there’s something so meaningful in the experience of going further, and there’s someone who is interested, someone who cares.

That was the first interview with Dr. Fauci in September 2020. That interview was going to be where we talk about his early life until 1996, with the discovery of antiretrovirals. By that point, I had watched countless interviews. I had never seen Dr. Fauci get emotional in anything I’d seen.

Some background about me is that I had founded a nonprofit media company called AIDS Films. In the mid-80s, I was making HIV prevention films. In 1988 I became the director of the Center for Special Studies running their HIV program. I did that for two years, in what Dr. Fauci calls the dark years.

He and I spent enough time together by the time of interview that he knew I had the experience of being on the front lines in an administrative way. I think the conversation was slightly different than what other journalists would have had, because he knew that he was talking to someone who had witnessed [those dark years]. It was a striking moment. I did not know when it became emotional, but we went further, and he answered. I was fully prepared for him to say, I’m uncomfortable getting that emotional on camera, I hope you won’t use that.

And there are other points where his eyes are filled with tears: when he’s alongside the white flags, he’s emotional, his lips are quivering. He understood that for this [documentary] to work, he had to be emotionally available in a way that he should not be in all his other media appearances. We did not ask him to do that. We did not have a conversation about that. But I owe him a tremendous gratitude for him just understanding it inherently, that his answers to these questions had to display a kind of vulnerability that as a public health person, he should not.

JJ: The impression I was getting from all his media appearances was that he was something of a hard-truth teller. But he’s also just a man. He’s lived through all these experiences, been very personally affected by them. It was powerful to see how those experiences left a lasting impact thirty years on.

AS: I agree. In the documentary there’s this humanizing aspect of Dr. Fauci’s life, like talking to his wife, and daughter and seeing him break down a little bit about experiences from 20, 30, 40 years prior. These are things that have stayed with him. The film explores in the AIDS crisis that these activists weren’t necessarily feeling the hard work that the physician-scientists were doing. You see him be emotional in the film. He’s very smart, he’s a fascinating person, but he’s also just a guy. That’s something that can be educational in and of itself, especially now, because he’s this towering figure in the public eye.

JH: Peter Staley, who’s more profiled than anybody else as an activist in the film—I had the chance to spend the time with him in the making of the film and in going to film festivals and media appearances. What he talks about is that it’s only now—watching the film, hearing Dr. Fauci’s perspective, hearing Dr. Fauci talk about the dark years—that he came to understand that in the whole time that they were storming the NIH and vilifying Fauci, they had no way of knowing what he was experiencing as a clinician. They never had stopped to think about it. Fauci didn’t ask for their attention and say, respect me because I’m a clinician. They had never stopped to think about the fact that he’s a human being who’s caring for patients, and he’s losing his patients, and how does that feel? And so, the activists have had to revisit a lot of their assumptions about the man when they conjure up all that anger. They now have to modify those memories to say, we were justified, but were we completely fair in terms of how we treated him as a human, for not being compassionate to the fact that he was suffering too?

LB: Do you think his attendance at the ACT UP meeting was a turning point for him? That was very brave of him to go.

JH: I think the turning point is actually earlier. It’s when Larry Kramer vilifies him and says, I call you a murderer. And he reaches out to Larry Kramer. If Larry Kramer had been well enough to be interviewed while we were making the film, we would have included him. The archive of Fauci and Kramer in television is insane in terms of the debates that they got into on different news programs There are multiple media appearances where Larry is just destroying Fauci and Fauci is quiet and takes it.

Larry Kramer, as the film suggests but does not get into in a deep way, really came to love Fauci. A big part of Fauci’s education came from that profound friendship with Larry Kramer. But I think the real turning point was Fauci’s immediate response to reach out to the person who is vilifying him so aggressively in the San Francisco Examiner. Going to ACT UP, which is a number of years later, is a more complex, more important moment. But the beginning of it was that initial response to the op-ed.

“You Can’t Compare”: Fauci’s Response to COVID-19

JJ: Were there opportunities for Dr. Fauci to meet the community as pushback was beginning to build with regards to the COVID-19 vaccine? I realize it’s just a completely different circumstance. But watching those scenes of him sitting in the gathering with all the activists around him and being very present was a powerful scene to see. But I don’t have an image of that happening in these last couple of years.

JH: I asked him if he had and if not, why not? You don’t hear that question in the film, but he did express that you just cannot compare the two. I don’t think that he feels that the conditions are such that there would be a constructive process. And that pains him tremendously. He has to live with that conclusion.

I think his confrontation, if you want to call it that, with Rand Paul is in that territory of not allowing mistruths to be spoken about the pandemic, about himself. If we asked him two and a half years ago, would you be standing up to a sitting senator and accusing this senator of putting your life at risk—he would’ve said, what are you talking about? But here we are.

EY: This is not a film about the coronavirus pandemic, right? That just happens to be the time period and is going to be a huge part of Dr. Fauci’s legacy. But I wonder, given that it was released within this pandemic, what your or your co-director’s thoughts were in terms of what you were hoping the short-term impact of the film might be. What are your thoughts as to an intended audience, given that was inevitably going to be the climate in which this film was released into?

JH: I love that question. When we were inspired to make the film, Fauci was not yet a household name, but we intuited that that’s where he was going. When we sold the idea of the film to National Geographic a month later, he was there, he was America’s doctor. We had no idea at that point as filmmakers, National Geographic as the presenter, that the country would become so divided. The film was not finished until August of last year, and then premiered a few weeks later at a film festival. But we could not have predicted the world that we were releasing this film into.

People have asked, the story’s not over and COVID is not over. Why release the film then? I’d be curious to know what you think, whether you think that we were right to finish the film when we did and whether the film will endure the test of time.

EY: I think so. I do. I understand the comments of, oh, the story’s not over. I think it stems from an misunderstanding as to what the story is. His name is so indelibly linked with COVID at this point that it’s an understandable thought to have. But inasmuch as it’s a story about a very remarkable person, I learned a lot about how the system that I’m going into works on a larger scale. And there’s something to be said for learning from the stories of your elders, as it were. It was a good, fun, and educational movie for me to watch. I was thinking during it, this is something that I would want to show my kids in the future, because I think things like these are very easily forgotten, and I wouldn’t want that to be forgotten.

AS: I agree. The film is not called COVID-19. It’s called Fauci. Speaking to documentaries in general, they are always going to be a snapshot of the time that they’re released in. I don’t think this one is necessarily any more marked by the time that it’s released in than anything else. The fact that there are these parallels to draw between the AIDS crisis and the current pandemic, it’s wild that Dr. Fauci was around and played such a prominent role in both. He was in his 40s in the 80s, and he’s about 80 now. Having that sort of linkage between past and present automatically gives the film an educational aspect that will help it stand the test of time.

JJ: I was thinking about what we were talking about at the beginning, how this story is unpredictable. A priori, we have no idea how certain twists and turns of history are going to play out. In my mind, there’s not really a reason to, especially given the practical limitations of filmmaking, follow [the story] indefinitely, because I don’t think we can expect a nice tidy bow at the end of whatever period we follow a person for.

But I also really enjoyed the film because by comparing a couple of different historical moments, especially the HIV epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic, I started thinking about questions of whether diseases are always political or politicized, whether that’s avoidable, and what determines whether a particular disease is going to be politicized as opposed to not? Those are some of the deeper questions and themes that I was thinking about while watching.

The documentary is available on Disney+. Also, please visit the annotation of Fauci in the LitMed Database.