By 1955, 75% of households owned a television, just seven years after their introduction to the marketplace.

Shawn Thomas

Shawn Thomas is a graduate of the NYU Grossman School of Medicine and the recipient of the 2018-2019 Rudin Medical Ethics and Humanities Fellowship grant. This article is one of his many works supported by this grant, and was inspired by Shawn’s love of medical television which first drew him to the field of medicine.

Introduction

No matter who you are or what your profession, anyone who has lived in the United States during the past eight decades has witnessed the tremendous popularity of medical television shows over the years. Medical shows such as ER, Grey’s Anatomy, Dr. Kildare and Marcus Welby, M.D. have been topping charts since the 1960s.

What is it about these shows that lure us to the screen? Perhaps there is something to be said about the heroics of the profession. They are saving lives, after all. But not all shows feature the fast-paced, heart-pounding action scenes so common in shows like ER. In fact, the comedy series Scrubs has derived its success almost entirely by lampooning the comically ordinary nature of hospitals and their staff. As a medical student myself, I like to think that people see medical shows as an opportunity to learn something new about an interesting, but relatively esoteric field. Becoming a doctor in the United States requires at least a decade of training, and even several years on top of this for surgeons and those in other highly specialized disciplines. Not everyone has the time, patience, or penchant for misery to obtain such knowledge. In this case, medical shows offer laypeople a window into this otherwise siloed profession.

Of course, this hinges on the assumption that what viewers see on television is an accurate depiction of reality. Regrettably, this is not always the case. Not that it always has to be – viewers are smart enough to know that Grey’s is not The Discovery Channel. But if you never watch The Discovery Channel, where else is your information coming from?

Especially when it comes to medical information, the content of medical shows has great potential to steer viewers’ understanding of health topics, either towards enlightenment or ignorance. The portrayal of doctors on television can serve either to elevate or tarnish the reputation of the profession, which could impact the average viewer’s willingness to meaningfully engage with their physicians. At the same time, producers and network executives are under tremendous pressure to create riveting content for the sake of attracting and maintaining viewership. These interests are not always aligned. The balance between entertainment and education is as old as broadcasting itself, and a revisiting of history illuminates the sociocultural environment of the United States that shaped the landscape of medical television today.

A Brief History of Broadcast Media

Before television, there was radio, and by 1937, 75% of American households had radios to listen to news, fireside chats, music, and educational channels. Audiences heard hundreds of broadcasters speaking on a variety of health topics, many developed in conjunction with the American Medical Association (AMA), to educate the public and reinvigorate interest in health and personal fitness. However, the battle between education and entertainment was already underway even during the radio era. By the late 1930s, broadcast networks had taken over the radio industry. Though there were plenty of channels dedicated to news and education, it was entertainment in the form of comedy and sports that kept listeners tuned in, and that kept advertising money flowing into the coffers of broadcast companies.

Television then, became a natural successor to radio as a new and improved broadcasting medium that could transmit both audio and video directly into American households. And because broadcast networks owned the airwaves, television would also follow the business model that drove decision-making in terms of which content would be played at which hours and on which channels. Television also appeared to offer a larger and more immediate audience given the rate at which it entered US households. For comparison, radios took 14 years to reach 75% of US households by 1937; televisions accomplished this feat in half the time, reaching the milestone in 1955. These aspects of the media industry at the time only served to bolster the notion that eyeballs and entertainment would continue to drive content in broadcast television, and that education would have to find a way to attract a critical mass of viewers if it was to have a chance of surviving in this economy.

To its credit, the medical field did its part to verify the content broadcast on television as it related to topics of health and medicine. Producers of television shows hired physicians to read scripts, and courted local physician groups to grant them an official “seal of approval.” The AMA remained as involved in television as it did with radio, and in 1955, the AMA established a committee which protected both the accuracy of medical information and the image of the physician as portrayed in television and film media.

As was the case throughout the history of broadcast media, medical television would often toe the line between education and sensationalism. In the 1950s, some medical television producers came under fire for broadcasting graphic depictions of operations, including a cesarean section which drew the ire of both medical professionals and religious groups, who accused these producers of exploiting the sensational nature of such images under the guise of education. The networks defended themselves by arguing that this level of detail was required by medical groups to maintain a seal of approval, and by extension, their viewership and advertising revenues.

Ultimately, as consumer tastes shifted, the AMA’s seal of approval began to lose its shine. The AMA, while still respected in an advisory capacity, began losing clout as a direct influencer of viewership. As a result, strict adherence to medical accuracy and realism became secondary to the goal of entertainment. Medical dramas were then seen as an optimal medium through which to educate the public about health topics while providing compelling stories that drew audiences to the screen.

Dr. Kildare and Marcus Welby, M.D.

In 1961, NBC aired the first episode of Dr. Kildare, which featured the young, newly minted, Dr. Kildare, portrayed by actor Richard Chamberlain. The character was originally featured in a series of films, and only later adapted for television. The AMA had previously stated that the field of medicine could benefit from the introduction of a television series featuring a friendly character who would appeal to the viewing public. Tall, blonde, handsome, and heroic, they may have found their answer in Chamberlain’s Kildare, a young physician with the confidence of a veteran. In addition to following the story of Dr. Kildare, the show also used each episode to showcase a different medical condition such as alcoholism, smallpox, blunt trauma, and countless others. In this way, Kildare provided an early example of a dramatic series that still managed to educate the public on medical topics. The format clearly resonated with audiences, as the show attracted a Nielsen rating of 25.6 during its debut season, making it the 9th most popular show on television that year.

The popularity of this style of TV series raised the possibility of using the show as a potential vehicle for delivering public health education to the American people. A notable example was an episode that focused on sickle cell anemia, a disease that was relatively unknown to the American public at the time as it primarily affected people of African descent. The episode was well received by both the network and the audience, and in fact, the episode’s writer was told several years later about a researcher of the disease whose career was inspired by the episode.

Public officials also attempted to latch onto this strategy but were met with resistance from the networks regarding controversial content. President Lyndon Johnson rang the writer for Dr. Kildare and asked for episodes on venereal diseases and oral contraception. However, despite support from the president of NBC, the board of directors refused to run the episodes. The board feared backlash from either audiences or advertisers, both of which threatened the company’s bottom line. This series of events served as a reminder that radical ideas in television, whether for education or entertainment, were unlikely to survive in an environment where cash flow was dictated by the whims of a fickle audience and powerful advertising partners.

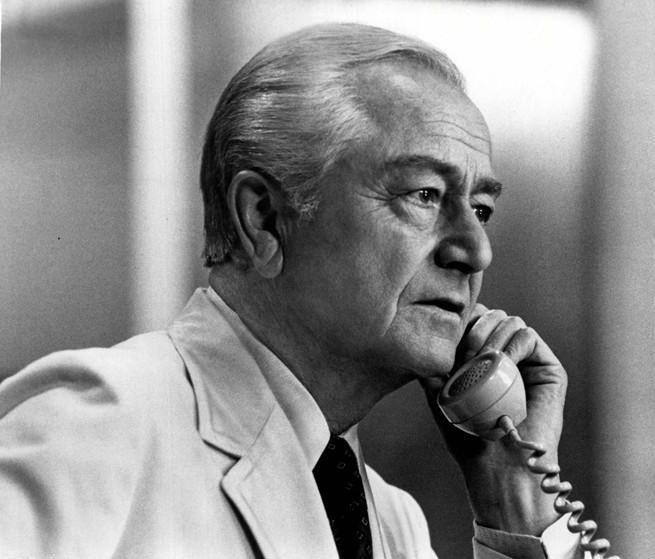

Medical television peaked for the first time with the introduction of Marcus Welby, M.D., featuring the old-school Dr. Welby and his young protégé, Dr. Steve Kiley, who jointly run a general medical practice in Santa Monica, California. A common trope in the show was the tension between the traditional, no-nonsense style of the elderly Dr. Welby and the new-age whippersnapper in Dr. Kiley, who often accused Dr. Welby of being stuck in his old ways. Their differences in bedside manner also provided viewers with an entertaining spectacle of the good-cop-bad-cop approach in medical practice. Another interesting feature of Welby was its departure from earlier shows featuring rare, one-of-a-kind, novel diseases and treatments, to focus on the more commonplace problems of patients at the doctor’s office. This approach to television had the effect of making the show relatable to average Americans and turned Dr. Welby into a hero in the eyes of the people. The strategy paid off, as Marcus Welby, M.D.became the number one show in television during its second season, garnering a Nielsen rating of 29.7 and over 17 million viewers per episode.

Dr. Michael Halberstam, a physician writing about Marcus Welby, M.D. for the New York Times in 1972, expressed his amazement (and poorly hidden chagrin) that his patients paid far more attention to Dr. Welby than they did to their own doctors. He spoke with the show’s creator, David Victor (who was also heavily involved with Kildare), who discussed how Welby was a “human drama with a medical background,” which focused on “the patient and the doctor, not the illness”. Doing the show this way helped avoid the pitfalls of Kildare, which began to lose viewership as the show increasingly focused on more and more obscure diseases.

Dr. Halberstam also praised the medical accuracy of the show, though he noted that the focus of each episode on a particular patient, or a particular family, gave viewers the false sense that they should expect this level of attention from all of their doctors. In reality, doctors may be taking care of hundreds of patients, all of whom compete for the doctor’s attention based on the urgency of their complaints or the difficulty with which a diagnosis is made. In addition, Dr. Welby rarely made any kind of medical error, only adding to his heroic persona. Yet “to err is human,” and like anyone else, doctors are prone to errors in judgment and decision making. In this way, the popularity of Dr. Welby and his style spelled trouble for the real-life physicians who could not hope to meet the expectations set out by their onscreen counterpart. Patients of this era would go their doctor’s office expecting to see Dr. Welby and be disappointed to meet a physician restricted by the complexities of the real world.

ER

Since Welby, several medical television dramas were produced, including M*A*S*H and Neil Patrick Harris’ Doogie Howser, M.D., but none reached the same level of popularity as ER, which aired its first episode in 1994. The show was first written in the 1970s by Michael Crichton, originally as a screenplay intended for a film. Crichton, who had recently graduated from Harvard Medical School, is best known as the author of Jurassic Park. In fact, Crichton was in the middle of pitching the idea for ER to Steven Spielberg, when the conversation turned to a book Crichton was working on about “dinosaurs and DNA”. Ultimately, the medical project was shelved while Spielberg adapted Crichton’s book for the big screen.

The pair revisited the project in the early 1990s and decided to convert the movie screenplay into one that seemed better suited for a television series. Crichton was adamant about the script that he had written, which, for better or worse, did an excellent job recreating the atmosphere in a real emergency department. While the ER team of Spielberg, Crichton, and producer John Wells defended the realism of the hospital environment, executives at NBC felt that there was “too much going on.” As one executive put it, “everybody loves going to see the movie Speed; no one wants to watch it every week.” After a great deal of negotiating, the show was picked up, but the script required reworking. Crichton had written the show from the perspective of a medical intern in the early 1970s. Now two decades later, the script was rife with outdated equipment and medications. Wells hired his friend, Neal Baer, to update the script. Baer, also a graduate of Harvard Medical School, had worked with Wells on China Beach prior to beginning his medical career. Baer became a regular writer on ER, as well as a showrunner and producer of several other series thereafter, including Law and Order: Special Victims Unit, A Gifted Man, Under the Dome, and Designated Survivor.

After putting together an ensemble cast featuring a young George Clooney as pediatrician Dr. Doug Ross, the pilot episode was shot, and the network executives came together for a viewing. Some of the executives were so taken aback by the hodgepodge of scenes they had witnessed that the network president warned the show creators that the series may never see the light of day. The network feared that the show was too fast paced, too graphic, and too filled with jargon for audience members to stay engaged. However, the audience surprised them. ER became the number two show on television in its debut season, spending three subsequent seasons in the top spot and staying in the top five for eight straight seasons. At its peak, the show drew in 48 million viewers – nearly half of American households with a TV. In short, the show was a hit unlike any show before it.

To go from almost never airing on TV to becoming a runaway hit, it is hard not to wonder whether those seemingly troubling aspects of the show were in fact the cornerstones of its success. Baer spoke in our interview regarding the tendency of older medical shows to merely “sprinkle in” medical talk, whereas the doctors in ER spoke to each other as real doctors would. Regardless of whether viewers understood what they were saying in these scenes, they were drawn into the show because it felt real. Similarly, the pace, chaos, and high stakes of the emergency room setting which were so carefully reconstructed provided a continuous stream of stimulation and excitement, both of which contributed to ER’s formula for success with viewers. Baer felt that the key to creating compelling television was to focus on characters who are thrown into difficult situations and have to make tough choices. Through these choices, the audience would see who the characters really were, what they were made of, and what drove them.

David Foster, who wrote and produced shows such as House and New Amsterdam, credited at least some of the success of ER to good timing. In 1994, the year that ER was first being produced, healthcare was on the public’s mind as Bill and Hillary Clinton were attempting one of the many efforts at healthcare reform. ER’s launch, coinciding with this sociopolitical moment, was fortuitous in that the public was primed to engage with a show that depicted challenging, complex, and emotionally charged topics in healthcare. Foster describes this interplay between television and culture as being one of the most challenging aspects of making a successful show, and it was a challenge that he himself had to grapple with when he began work on New Amsterdam.

The producers of ER used the show’s popularity as a tool to shed light on a variety of medical and social issues such as AIDS, organ transplantation, and breast cancer genetics. These episodes triggered discussions among physicians and even drove viewers to seek out further health information on their own. Wells said it best when he remarked, “The show is not about telling people to eat their vegetables, but if we can do that in an entertaining context, then there’s nothing better.” In fact, ER may have had more of an impact in this regard than Wells may have realized at the time. The producers, in conjunction with the Kaiser Family Foundation, undertook a study to measure whether viewers retained the medical information that was mentioned in the show. A study with over 3500 survey respondents showed that after the airing of an episode about the human papilloma virus (HPV), 60% of viewers knew that it was associated with cervical cancer, compared to 19% before the episode. Though this percentage dropped off to 38% six weeks after the episode, this study was the first to convincingly demonstrate the impact that the show could have on educating the public. The caveat, of course, is that viewers are just as likely to retain erroneous medical information in this context. This requires that show producers accept their responsibility as de facto health educators if they wish to avoid the spread of misinformation.

During the early 2000’s, the producers of the show saw an opportunity to showcase a humanitarian crisis underway in Western Sudan. While news programs had largely avoided discussing the War in Darfur which had killed hundreds of thousands and displaced millions more, the producers of ER created a story arc shot in Africa which educated viewers as to the brutality of the crisis. After 15 seasons in total, episodes like this defined the legacy of a show that was able to engage viewers not just about life in the hospital, but also about public health issues and world affairs.

Scrubs

As the fever pitch popularity of ER began to wane, other medical shows tried to grab the spotlight. Bill Lawrence, who had previously worked on the political sitcom Spin City, began musing about the possibility of starting a medical TV show. In interviews, Lawrence describes how the idea for the show came up over drinks with his best friend from college, Jonathan Doris, a physician who became the inspiration for the show’s lead character, John, “JD” Dorian. What resonated most with Lawrence was Doris’ description of the stress, anxiety, loneliness and fear which came with medical training as a new doctor – not unlike those of any new job, but compounded by the fact that people’s lives were on the line day in and day out.

Through these stories, Lawrence envisioned a show which followed young doctors as they journeyed through life and training, buoyed by the support of their fellow trainees who are battling similar circumstances. In contrast to the heroics which shrouded television doctors of the past, Lawrence wanted audiences to view doctors as he saw Jonathan Doris – just a friend from college with his fair share of achievements, paired with the struggles and shortcomings of any normal person. The lyrics of the opening theme song (“Superman,” by Lazlo Bane) are true to this sentiment:

I can’t do this all on my own//No I know – I’m no Superman

Lawrence’s background in comedy allowed him to infuse the show with his unique brand of humor. This not only gave the show its original flavor in the landscape of medical television, but also provided the comic relief necessary for the more poignant scenes, of which there were many. In contrast to the intensity and seriousness of prior medical shows, Scrubs instead evoked laughter by poking fun at the many banalities and unglamorous aspects of hospital work.

Scrubs was filmed in an abandoned hospital building which was refitted for the production. Bill Lawrence once quipped that the sad state of disrepair of the American healthcare system was at least partly responsible for the show’s success in this regard. The setting gave the show a realistic aesthetic, as opposed to filming with propped sets in an off-site location. As for the show’s content, Lawrence explained that almost every situation seen in the show was taken from the stories of Jonathan Doris and a few other doctors who contributed to the show. Lawrence greatly valued the realism of the show and named characters after the doctors who contributed their stories. Likely for this reason, the show was embraced by the medical community, which recognized elements of their own grueling training through the stories told on Scrubs.

Scrubs enjoyed great success on national television, peaking in year two of its nine-season tenure. The second season was the 14th most popular show on television that year, drawing in 15.9 million viewers on average. When comparing a comedy like Scrubs to its dramatic predecessors, it would probably not be accurate to attribute the show’s success to a change in audience taste. For one, the show did not enjoy the same level of success as previous shows in the genre, such as ER and Marcus Welby. In addition, medical television shows after Scrubs, which were much more drama than comedy, easily surpassed the show in terms of ratings. The point is not to diminish the standing of Scrubs in the history of medical television, but instead to suggest that the popularity of Scrubs was bolstered by a bloc of viewers who were drawn to the show’s levity amidst a genre which tended towards solemnity. For all these reasons, Scrubs remains a mainstay of medical culture for its ability to realistically capture the myriad emotions of medical training via 20 minutes of light-hearted banter.

House, M.D.

House was one of the most popular medical dramas on television since ER, reaching its peak on the ratings chart during its third season, making it the fifth-most popular show on television during that year. What is perhaps more interesting is that the idea for such a successful medical show came not from a doctor, but instead from a lawyer-turned-screenwriter.

David Shore attended law school at the University of Toronto for all of two weeks before losing interest in the profession, but he completed law school and even practiced law for several years before deciding that the time was right to make a move to L.A. to pursue his then budding passion in writing and comedy. Since that time, Shore’s background in law seemed to serve him well, as he was able to obtain writing positions with shows such as NYPD Blue, The Practice, and Law & Order. To go from corporate lawyer to writer, producer, and eventually show creator is not exactly a typical career path. And yet Shore’s ability to break in can be seen as an extension of what was occurring in the medical field. In the post-ER world, professionals of all fields were finding themselves in high demand in the entertainment industry for their expertise on otherwise obscure topics, in order to bring a higher degree of realism to television drama.

Even still, Shore’s entry into medical television is a bit of stretch. What could a lawyer bring to the table in terms of medical drama? In fact, Shore’s idea for House was to focus on a team of physicians who worked as medical detectives, aiming more for Crime Scene Investigation as opposed to ER. That being said, Shore still opted to bring in physicians to add realism and to inform the script from a medical perspective. A notable member of this medical team was Lisa Sanders, known for her long-running New York Times column “Think Like a Doctor.” Dr. Sanders’ column outlines a medical mystery that stumped physicians, inviting readers to solve the mystery for themselves. Shore has cited her column as inspiration for the show’s focus on solving medical mystery through extremely detailed investigation, albeit using tactics that were unethical or outright illegal. Shore also drew inspiration from the quintessential detective Sherlock Holmes, from which the show’s lead character derives his name. The show contains many other references to Holmes’ character and backstory but draws mainly on his relentless pursuit of puzzling mysteries and their solutions.

David Foster, one of the early writers and producers of House, weighed in on this aspect of the show in our interview.

I think the most fundamental thing with House that was new and different from the other shows, was the notion that when the doctor walks into a room, they don’t know what’s going on. It’s a process of trial, error, and discovery to figure it out. For the public, when a doctor says, “this is what’s going on,” they think that it all happened in a moment. But it was really a process to get there, and I think most patients, especially in 2004 when we started House, that concept was obscure to them. The reality is that doctors were coming in, talking to you, saying “give me a minute,” then walking out and saying, “what the hell is this?” But it’s stock and trade of how we all practice, and for patients, it’s not how they thought we practiced.

Just creating a show about medical investigation, however, would not be enough to lure audiences to the screen. In the same way that ER was more than just “the medical ethics story of the week,” Shore realized that the success of House would hinge on the development of interesting characters to drive the show forward. From this insight was the inspiration to create the character of Gregory House, an abrasive, cold physician who limps around with a cane, never far from a bottle of Vicodin to nurse his ongoing addiction. He has no tolerance for incompetence and distraction, and the show is littered with witty quips and jabs directed at his colleagues, superiors, and even patients themselves, for whom he shows little regard outside of the intellectual challenge that their illnesses present.

House became a huge hit, drawing in nearly 20 million American viewers at its peak during the third season. The character of Gregory House, portrayed by British actor Hugh Laurie, was the centerpiece of the drama, with Laurie earning several Emmy nominations and securing multiple Golden Globe awards for his work on the show. At one point, he was the highest paid actor on television, earning over $400,000 per episode.

Not everyone was so enthused with the message being sent by House’s success. In particular, Foster recalls that physicians would write and call in to the show, irate at the notion of a “pill-popping” doctor who treated his patients with such disdain and disrespect. Understandably, there were multiple issues about Gregory House’s character with regard to the profession of medicine. First, the show gave the impression that to physicians, patients and their illnesses are nothing more than an intellectual game. Second, even those patients who appreciate House’s relentless determination may come away with the wrong idea that their own real-life physicians are willing to cross ethical and legal boundaries for the sake of patient care. In the same way that patients of the 1970s used the incorrigible Dr. Welby as their standard-bearer, physicians could never expect to live up to the expectations set by Dr. House. And third, physicians worried that patients would walk away from an episode of House thinking that a “pill-popping” doctor would be tolerated in the field of medicine, his diagnostic acumen notwithstanding.

However, gone were the days of AMA oversight and seals of approval. Despite how physicians felt about the show, the reality was that they had little clout in Hollywood. The writers and producers of television shows in the modern era only had to answer to the networks, so as long as the show was successful, anything was fair game. Foster, a Harvard-trained physician himself, was sympathetic to the concerns of other physicians, yet he still shrugged off the pushback as mere “hazards of the job.” With regard to House’s prickly personality, Foster notes that nurses who work closely with physicians would not feel that House’s demeanor was so far from the ordinary. At the end of the day, he says, television portrays the experience of one doctor, one patient or one story, not what happens on average. If patients really wanted to see the average doctor, they could simply turn off the TV and walk into the local clinic.

Grey’s Anatomy

No discussion of medical television would be complete without including one of the longest running shows in the history of medical drama. Grey’s Anatomy, which began in 2005, continues airing episodes to this day, with contract renewals inked for a 16th and 17th season in the future.

The show derives its name from the popular textbook of medical anatomy, Gray’s Anatomy, though the slight change in spelling is meant to focus our attention on Meredith Grey, the show’s leading character. This detail alone captures an important departure from medical dramas of the past, which is that the star of the show features a strong, leading woman, portrayed by actress Ellen Pompeo. The creator of Grey’s Anatomy, Shonda Rhimes, noted a troubling trend in the film industry of women being relegated to superficial roles without any opportunity to explore the depth of their characters. The cutthroat environment of the surgical training program at the fictional Seattle Grace Hospital provided the perfect setting to allow her leading women not just to shine, but also to reveal other, more negative aspects of their personalities. It was not about placing women on a pedestal, but more so depicting a multifaceted picture of women that had been conspicuously absent on television up until this point.

This was not the only cultural barrier that Rhimes sought to break down. In creating the ensemble cast for this soap-opera style television show, Rhimes had no preconceived notions as to the race or gender of particular characters, instead allowing the audition process to select for these factors organically. In doing so, Rhimes created a cast of characters that was one of the most diverse in television history, even maintaining this diversity in the casting of extras and other small roles.

Recall the ways in which Welby turned the audience into the stars of the show, focusing on peoples’ everyday problems in a way that connected with many millions of Americans. The unique casting method used for Grey’s Anatomy brings the audience back to forefront, creating a cast that reflects the rich diversity of the American audience that propelled the show to its success. Grey’s Anatomy reached its highest position on television charts during its second season, where it drew in over 22 million viewers on average, making it the fifth most watched show on television that year. To compare a show like Grey’s to the dominant ER may be difficult to justify, considering the regularity with which ER topped ratings charts, and the inability of Grey’s to push past fifth place. What cements the show’s place in medical television is its longevity and consistency; not necessarily its ability to draw in the most viewers, but to reliably draw in many viewers. As an example, while ER was tremendously popular during its first 10 seasons, never lower than the sixth most popular show on TV, their viewership precipitously fell after this point, not even making the top 30 during the 14th season, and eventually coming in 26th during the 15th and final season. As members of the ER cast faded away in pursuit of other projects, so too did the television ratings. Grey’s, on the other hand, has been one of the top 20 shows on television for its entire duration, outside of a single season in which it came in 21st. Though this discussion may seem like a reductive numbers game, viewership patterns tell us a great deal about how shows resonate with audiences. The take home message here is that Grey’s has carved out a niche of dedicated viewers who have stayed loyal to the show for the better part of two decades, withstanding numerous cast changes throughout its tenure.

Like other medical television shows of the last few decades, Grey’s Anatomy has come under fire for its unrealistic, oftentimes melodramatic portrayal of hospital life. As in the case of House, it’s possible that much of this noise has come from the medical field itself, nurses and doctors who have taken issue with one element or another. But some of this criticism has been more pointed than just angry letters and phone calls. In recent years, multiple papers have been published in academic journals, studying the effect of the show on peoples’ perceptions of hospital care and their satisfaction levels after a hospital experience. One study of traumatic injury noted that compared to a real hospital, patients in Grey’s Anatomy had a higher mortality and higher rates of surgery, with paradoxically shorter lengths of hospital stay and lower percentages of patients going to long-term rehabilitation facilities. It’s hard to make too much of the so-called “Grey’s Anatomy effect” – after all, it’s not the hard-hitting science that draws viewers to the screen. Yet the lesson from ER’s HPV study bears repeating, which is that viewers tend to subliminally retain what they see on TV, regardless of its accuracy.

New Amsterdam

In our interview, Dr. Foster referred to the interplay between television, social culture, and politics as one of the most rewarding aspects of his work, but also one of the most challenging. Successful television shows, he argues, capture some public sentiment and weaves that into a compelling story driven by complex characters. The sociopolitical climate goes a long way in turning those abstract concepts into realities for viewers.

One storyline of Barack Obama’s early presidency was the campaign for and ultimate passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which was officially signed into law in 2010. The passage of the law was seen as a light at the end of a tunnel, paved with the failed attempts at healthcare reform of past decades. However, the ACA was not without its opponents both in Congress and in the healthcare system, and the 2010’s were defined by tumultuous legal battles over the scope of the law, ambivalent data regarding cost reduction, and most importantly, the lingering question of whether or not average Americans were actually seeing improvements in their day-to-day healthcare. As the decade came to a close, there was a sense that despite the incremental improvements offered by the ACA, there was much to do in the way of reshaping our healthcare system around patients, instead of around powerful insurance groups, pharmaceutical companies, and hospital executives.

These issues provided the ideal backdrop for the creation of New Amsterdam, a recent medical drama based on the book Twelve Patients by Eric Manheimer, former Medical Director of the iconic Bellevue Hospital in Manhattan. In fact, the set of New Amsterdam is none other than Bellevue Hospital, where camera crews and production teams are often seen when filming is in session. The show centers around Dr. Max Goodwin, portrayed by actor Ryan Eggold, who is tasked with rebuilding a hospital that has fallen victim to the plagues of modern healthcare. In addition to weaving through red tape, Dr. Goodwin and his colleagues tackle issues such as healthcare for prisoners, socio-legal aspects of child psychiatry, and multicultural competence for physicians practicing in a diverse, New York City hospital.

While the show can sometimes be heavy-handed in its advocacy of social justice, the show’s first season was undeniably successful, ranking 15th amongst network television shows, and drawing in an average of 11 million viewers. The show has also been renewed through the fifth season, further bolstering the success of the show and the network’s confidence in its future.

An element of the show that appears to resonate with audiences is the larger-than-life persona of Dr. Goodwin, who appears to wield unilateral decision-making authority at the New Amsterdam Hospital and is unafraid to use it. Only adding to his grandeur is the revelation of his own ongoing battle with cancer. Unlike dramas with an ensemble cast, shows like House and New Amsterdam feature headstrong lead characters who are willing to go to any length to achieve their goals, whether solving a medical mystery or upending the healthcare system. Perhaps related to the recent takeover of Hollywood by superhero movies, there seems to be a certain comfort that audiences find in a “knight in shining armor.” In the case of House and New Amsterdam, Foster surmises that in characters like Dr. House and Dr. Goodwin, people see the doctor they would want for themselves or the people they care about. In a world where healthcare feels broken, it is easy to escape to a world where a tireless advocate leaves no stone unturned on our behalf.

It is interesting to note that the success of New Amsterdam appears to be driven by a collective understanding by the public that something is seriously wrong with our healthcare system – not just in our hospitals, but more so the social determinants of our health. Foster, who also writes for and produces New Amsterdam, noted that the show’s success would be unlikely if not for our current state of healthcare. To have to introduce the concept of a broken healthcare system, and then to create a show around that, he says, would be too much of a leap for audiences to really resonate with the series. In the current era, audiences have been primed not just by the news media and public debate, but also by their own negative experiences navigating the healthcare system. As a result, the show can much more easily tap into that energy and create a successful drama around it.

Is there such a thing as hitting too close to the mark? At the time of this article’s composition, the 2019 novel coronavirus has brought the world to its knees. Shelter-in-place orders had effectively quarantined people to their homes, bringing normal life grinding to a halt. All the while, the virus continues to wreak havoc on our economy and strain our healthcare systems in New York City, which became the early national epicenter of disease and across the globe. In the midst of this crisis, New Amsterdam was coincidentally set to air an episode about a flu pandemic. The episode was scrapped, with show creator David Schulner saying, “the world needs a lot less fiction right now, and a lot more facts.” This observation highlights a fundamental tension in producing medical television shows, which is to create culturally relevant content with the understanding that introducing occasional inaccuracies is an inevitable part of the creative process.

Conclusion

Medical television shows have undergone many transformations since the days of Welby and Kildare. Motivated by members of the profession, shows of that era went out of their way to showcase their eponymous physicians as model citizens of impeccable moral caliber. These shows took advantage of their characters’ ethos to teach both their fictional patients and real-life audiences a thing or two about their health, even garnering input from the president regarding content. As the years went on, viewers became a more powerful stakeholder for television production than even physicians themselves. Though physicians found a role in this new landscape, their input was more creative than regulatory. To capture larger swaths of the viewing public, education took a backseat, and the formerly pristine reputation of TV physicians was readily sacrificed for the sake of creating captivating characters and storylines.

That modern medical television shows continue to strive for a passable degree of medical accuracy likely says less about producers’ rigid standards for truth and more about the inherent drama which exists in the medical field. One can imagine that an emergency medicine physician who watches ER might find themselves bored in the opening episode, which was perhaps too reminiscent of the shift they just completed. Yet to become the most popular show on television at the time says a great deal about how fascinating these environments and issues are to the non-medical viewer.

Though present-day television shows may not be so explicit in their efforts to educate viewers, there is no doubt that viewers are forming impressions and viewpoints based on what they see. In the case of the HPV study conducted by ER producers and the Kaiser Family Foundation, viewers are subconsciously learning specific pieces of medical knowledge every time they tune in. However, this learning can go both ways, lending itself to the possibility of disseminating misinformation. The results of this study support an ethical imperative for accuracy in medical television shows, for the furtherance of a society that is better-informed on topics of public health.

In the same way, television producers are looking to their audiences for cues as to what to create next. Television, medical or otherwise, will always inextricably linked to our present-day culture, lifestyle, values, and politics. Especially in a world where the survival of television shows is driven by broad appeal, creators of these shows must learn to tell compelling stories while capturing the sentiment of the times, lest they be cancelled prematurely. And as the times change, so too must the content, making the world of television an existential race to hit the next moving target.

Looking to the Future

In our interview together, Dr. Baer expressed his apprehension about the future of medical dramas, feeling that many of the new shows in the genre are treading ground that has already been covered. Creating shows for a broadcast network requires appealing to common ground, and there is only so much common ground to go around. Streaming services and pay-per-subscriber business models may be redefining the landscape of television in this regard. The new model presented by services such as Netflix, Hulu, and HBO rely less on broad appeal and instead on content personalization. As opposed to making a few shows watched by huge audiences, these services have favored creating many shows developed for niche audiences, tailored to the specific tastes of smaller blocs of viewers. The result is that show producers may feel more comfortable producing edgier, more novel content, without the burden of pacifying advertisers, board directors, and other network stakeholders. While these newer shows will still have to draw in viewers, the target is not necessarily the number of viewers, but rather the number of new or different viewers. Compared to the previous model, success in this new ecosystem will rely on experimentation and unorthodox approaches to television to bring new audiences into the fold.

Consider a show such as Kildare, which lost popularity and network support over its tenure due to its increasing focus on rare, obscure diseases. In the new era of personalized television, this style could very well have survived on a streaming platform, perhaps appealing to a particular niche of the audience with a scientific bent. A different series could be set in Washington, D.C., following a group of policymakers who weave their way through political crossfire as they attempt to pass major healthcare reform through the chambers of Congress – this show could be targeted for those audience members with an interest in policymaking and political games. Yet another series could be written from the perspective of a lawyer who investigates malpractice and fraud in hospitals, aiming to draw in those viewers interested in detective stories and legal dramas. All of these would be in addition to already existing shows which center on the stories of physicians and patients in hospitals. One could even envision “crossover” episodes, in which characters from each of these different series encounter each other during climactic moments in the story, giving the audience a chance to see how the different pieces of the healthcare puzzle ultimately fit together.

Healthcare is an incredibly diverse, multifaceted industry which encompasses hundreds of different disciplines. The boon for producers working in the era of content personalization is that within this genre, there is something for everybody. Creators can produce shows based in relatively niche disciplines, without having to sacrifice authenticity in pursuit of the lowest common denominator. We may live in the information age, but information overload makes it hard for us to separate the signal from the noise. This hasn’t stopped the public from reasserting themselves in the doctor-patient relationship, which now resembles a partnership more than the formerly paternalistic model. Given the degree to which television has permeated everyday life, the right shows can reframe our perspectives about health issues, not just for the betterment of individual health, but also for the sake of a more productive national conversation about healthcare. Now more than ever, producers have an opportunity to refocus content around this vision, so long as we are willing to take advantage of the changing winds in our midst.

Sources

Books

Stempel, T. (1996). Storytellers to the Nation: A History of American Television Writing (2nd ed.). Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

LaFollette, M. C. (2013). Science on American Television: A History. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Brooks, T., & Marsh, E. (2007). The Complete Directory To Prime Time Network and Cable Tv Shows, 1946-Present. New York: Ballantine Books.

Journal Articles/Studies

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2002). The Impact of Tv’s Health Content: A Case Study of ER Viewers. Survey Study. Published online on 30 June 2002. Accessed April 21, 2020.

Brodie, M., Foehr, U., Rideout, V., Baer, N., Miller, C., Flournoy, R., & Altman, D. (2001). Communicating health information through the entertainment media. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 20(1), 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.20.1.192

Serrone, R. O., Weinberg, J. A., Goslar, P. W., Wilkinson, E. P., Thompson, T. M., Dameworth, J. L., … Petersen, S. R. (2018). Grey’s Anatomy effect: television portrayal of patients with trauma may cultivate unrealistic patient and family expectations after injury. Trauma Surgery & Acute Care Open, 3(1), e000137. https://doi.org/10.1136/tsaco-2017-000137

Podcasts

iHeartMedia (Producer). (2020, March 31). Fake Doctors, Real Friends with Zach Braff and Donald Faison. [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from http://www.iheart.com/podcast/1119-fake-doctors-real-friends-60367049/. Accessed April 5, 2020.

NPR-KQED (Producer). (2005, February 4). Fresh Air: Zach Braff Scrubs In [Audio podcast]. Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=4486459

Interviews

Dr. David Foster

Dr. Neal Baer

Pop TV. (2017, April 4). The Story Behind: ER [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com

/watch?v=40cI8vZ1b0U

Online Articles

Littleton, C. (2016, January 17). Ted Sarandos Blasts NBC’s Netflix Ratings Info: ‘Remarkably Inaccurate.’ Variety. Retrieved from https://variety.com/2016/digital/news/netflix-ted-sarandos-blasts-ratings-nbc-1201681727/. Accessed April 20, 2020.

Halberstam, M. J. (1972, January 16). An M.D. Reviews Dr. Welby of TV. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/1972/01/16/archives/an-md-reviews-dr-welby-of-tv-dr-welby-of-tv.html. Accessed April 20, 2020.

Fogel, M. (2005, May 8). ‘Grey’s Anatomy’ Goes Colorblind. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/08/arts/television/greys-anatomy-goes-colorblind.html. Accessed April 20, 2020.

Rhodes, J. (2005, April 14). Thriving Ratings for a New Patient on ABC. The New York Times. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2005/04/14/arts/television/thriving-ratings-for-a-new-patient-on-abc.html. Accessed April 20, 2020.

Vlastelica, R. (2016, October 10). Scrubs was goofy, profound, and a key link in the evolution of TV comedy. The AV Club. Retrieved from https://tv.avclub.com/scrubs-was-goofy-profound-and-a-key-link-in-the-evolu-1798252849. Accessed April 20, 2020.

Gibson, S. (2008, January 3). The House That Dave Built. University of Toronto Magazine. Retrieved from https://magazine.utoronto.ca/people/alumni-donors/david-shore-house-creator-television-producers/. Accessed April 20, 2020.

Springer, S. (2012, May 22). ‘Grey’s Anatomy’ creator, actress discuss media diversity. Retrieved from https://inamerica.blogs.cnn.com/2012/05/22/greys-anatomy-creator-and-actress-discuss-media-diversity/. Accessed April 20, 2020.

Young, S.C. (2009, March 24). ‘ER’ closes doors, leaves satisfying legacy. Today Television. Retrieved from http://www.today.com/id/29843242. Accessed May 6, 2020.