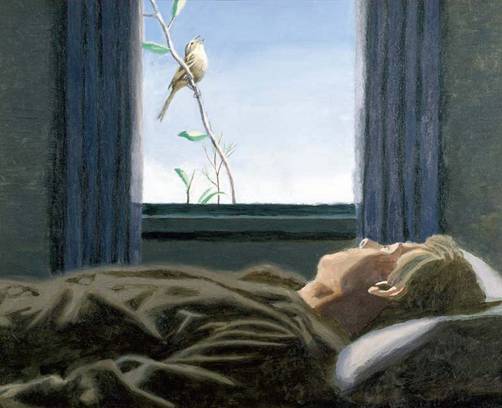

Painting by Robert Pope

Dr. P Ravi Shankar

Dr P. Ravi Shankar is a faculty member at the IMU Centre for Education, International Medical University, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. He is supporting the Department of Language, culture and communication with offering health humanities to the health science students at the university.

I was feeling bitterly cold. The shivering did not stop. Unintelligible voices began coalescing into words. Words joined into sentences. I was in the twilight zone between wakefulness and sleep. I heard my father’s voice talking to the nurse. The nurse put one more blanket on my body. I slipped in and out of consciousness.

I gradually returned to the world of the living. Recovering from anaesthesia is different from waking up from a normal sleep. My voice was a croak. Speaking was difficult. I was soon shifted from the recovery room to the ward. My surgeon visited me as he was leaving for lunch. He explained that I would find it difficult to speak for a few hours due to the endotracheal tube placed down my trachea during the surgery. I was still shivering—a reaction to the anaesthetics used–though the intensity was decreasing.

Today on thinking back about the event I am reminded of the story “Blankets,” by Native American writer Sherman Alexie. In the story the protagonist’s father is feeling cold after his amputation and the protagonist asks the duty nurse for an additional blanket. The request is met with unwillingness and reluctance and the main character’s struggle to find a blanket to keep his father warm forms the basis of the story.

I had been admitted to the hospital the previous night for the early morning surgery. I was worried; it was the first major surgery of my life. May 1991 was hot and humid in Mumbai, India. Compared to the summers of today, the weather was milder. The last three decades unfortunately, have seen the average temperature increase by two to three degree Celsius. Being a medical student who had witnessed different surgeries during my clinical postings I knew many things could go wrong. I was a firm believer in Murphy’s laws: if something can go wrong it will and if two things can go wrong, then the one which will do so is the one which can cause the greater damage! I was wheeled into the operation theatre and an intravenous line started. The anaesthetist started injecting thiopentone sodium. He asked me to count backwards from 100. I was always worried about anaesthesia. What if it did not work? What if I woke up midway through the surgery in pain? What if I did not wake up ever? I counted till about 94 and then remembered nothing till I woke up in the recovery room shivering.

Modern anesthesia is one of humankind’s greatest inventions. Surgery progressed only after intraoperative pain was conquered. Surgeons could now carry out longer and more intricate surgeries. The process of anesthesia has become smoother and quicker and with intravenous agents the process is nearly instantaneous. Before anesthesia, surgery was a torture. The patient was tied down and alcohol, psychedelic plant products and opioids were the only pain killers available. Only a very brave and stoic person would consent for surgery. The other major problem was infection which was rife in the pre-antibiotic era. I counted my blessings. But medicine is in a constant state of development, and not just as regards anesthesia. Today most meniscectomies would be carried out using a laparoscope. Open surgeries are a thing of the past.

My right leg was covered in bandages. For the first two days I was not allowed to leave my bed. I got a taste of what being bedridden really meant. Having to eat, drink and carry out natural functions on the bed was difficult and unnatural. Being confined to the bed narrows your field of view and shuts down your perspective. The artist Robert Pope, who died young from cancer, has captured the unique perspective of the bedridden very well in his paintings. Robert Pope (www.robertpopefoundation.com) was a Canadian artist who painted about healthcare and healing as a cancer patient. I and my cofacilitators have been using his art works in health humanities modules for over a decade.

On the third day my cast was removed and an elastocrepe bandage applied. I was advised to start walking and weight-bearing on the leg. I started walking around the corridor with a walker. I was beginning to feel home sick. I was in a room with three other persons; not much privacy. Visitors were allowed only during the evenings. The food was OK but nothing like the home cooked version. Once you are admitted to a hospital you are in a strange land and everything familiar is left behind. Passing time was difficult. I didn’t have much reading material, there was no television in the room, and mobile devices and the internet were still in the future.

The twisting injury to the knee two weeks ago made it impossible for me to straighten my leg. Walking was difficult and my deformity was obvious when I wore pants. My doctor was a loud and boisterous man with a handlebar moustache who wore light-colored safari suits. The safari suit was once a ubiquitous status symbol in India which over the decades has steadily lost popularity. He was an old-fashioned surgeon who believed in wide incisions and liberal exposure.

I was in hospital for around a week. My stitches were removed the day before my discharge, and I was referred to a physiotherapist. The knee becomes stiff very quickly. Muscles also weaken quickly if not used. The physiotherapist made me do exercises to improve my muscle strength. Astronauts in the zero gravity of space do not have to use their muscles as much as on earth and must do active exercises to maintain their muscle mass. Active movements of the knee joint were fine. Passive flexion of the knee was pure torture. The joint was stiff and the range of motion less. Bending it beyond the limited range led to severe pain. My physiotherapist was an interesting character who loved playing football. He reminded me, “Now you know what patients go through when you write ‘mobilize the joint’ following a joint surgery.’’

This was the first hospitalization of my life, and it gave me a deeper insight into the patient perspective. I learned the value of family relationships. My family had been saving for some time to buy a video cassette player; my surgery and the hospitalization expenses meant that this was no longer possible. In the 1990s health insurance was uncommon in India and hospitalization and medical expenses created a significant dent in a family’s finances. I also had to miss some of my final year classes as I was not fit to travel, and my parents did not want me to readjust to hostel life till I was better. Even a small joint injury had a surprisingly long-term effect.

I passed my exams the next year and began my house surgeon training. I tried to be empathic and kind to my patients. This becomes impossible when you had to deal with over a hundred patients in small, cramped outpatient departments. The wards had seen better days. The sanitary facilities needed a major upgrade. Patients were on the beds, on the floors, on the corridors, everywhere. Being empathic in these circumstances when you were cramped for space, time and resources became near impossible.

Being on the other side of the table– or the scalpel, so to speak– makes me consider the patient perspective when I am caring for my patients. Reflecting on one’s own experiences as patients is important for health practitioners and healthcare students. Knowing that a patient may be struggling and making financial sacrifices in other areas to access treatment has sparked my interest in health economics, the cost of medicines and treatments and a lifelong mission to promote the more rational use of medicines. I have not always succeeded in being a kind, and empathetic doctor, but I have always been able to reflect on my experiences and strive for continuous improvement. I and my cofacilitators also often utilize this reflective experience during our health humanities modules. Our days as health practitioners are often chaotic, rushed and draining but we must be thankful that we are physically and mentally whole and should offer support to individuals who are sick, frightened and afraid!