By Sebastian Charles Galbo

Patients at the Pennsylvania Hospital in the late eighteenth century rarely enjoyed the hospital garden as a space of tranquil solitude. Just over the garden walls, past the blue wisteria and azaleas, had gathered the regular Sunday spectators who chattered about the patients who walked the lawns. To deter their noisy curiosity, the hospital built a fence and required townspeople to pay a 4-pence fee to view the patients, proceeds which funded the care of invalids with physical and mental illnesses. While modern readers would revile such a display of patient objectification, there were few alternatives to disbanding the adamant spectators—hospital staff settled for a garden that served at once as a space of convalescence and public display.

Courtesy of the Pennsylvania Hospital Historic Collections

The Hospital Garden: From Monastic Retreat to Organized Clinical Space

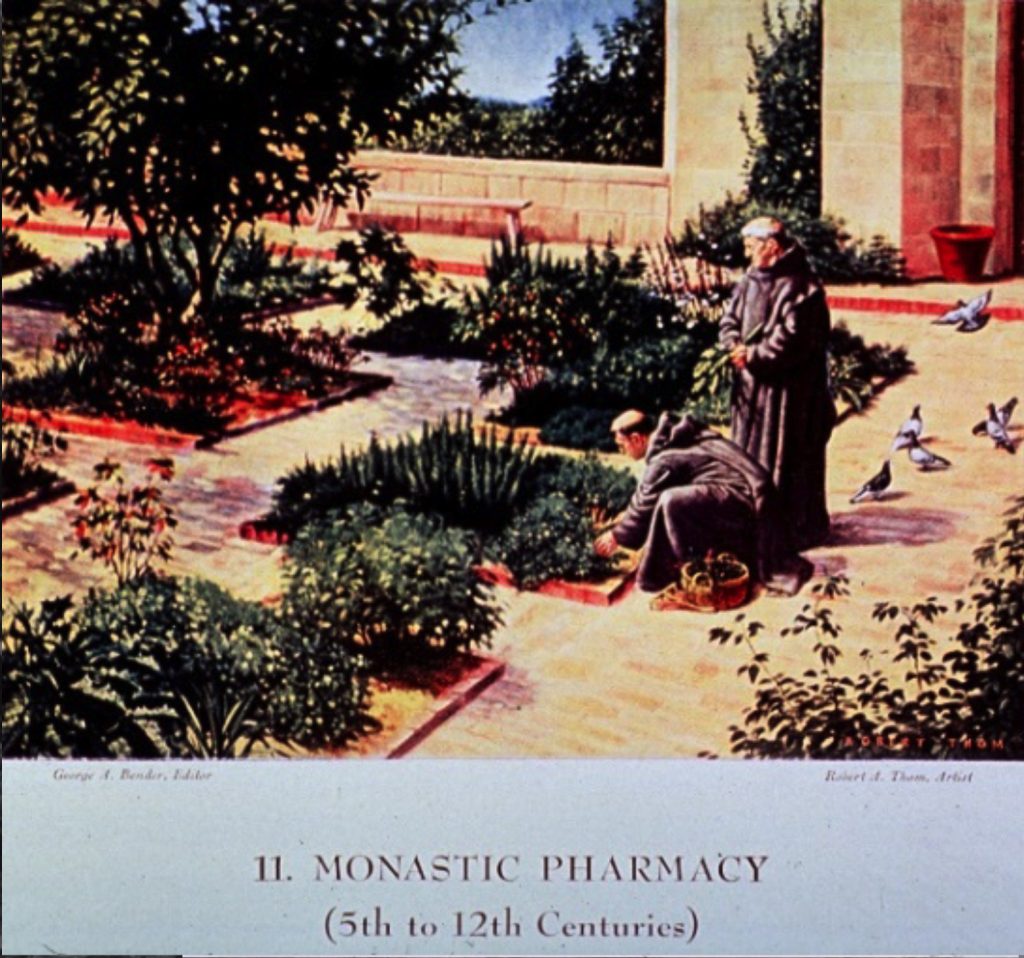

Morbid patient objectification, of course, was never the express intent of hospital gardens. Over the course of many centuries, hospital gardens have evolved into valuable clinical tools for patient care and rehabilitation. In The Hospital: A Social and Architectural History, John D. Thompson and Grace Goldin trace the ideological and architectural evolution of the hospital as an institution of social power and patient care. The rehabilitative potential of gardens and cloistered green spaces was recognized by European monastic communities and hospitals during the Middle Ages. Remarking on the gardens of his hospice in Clairvaux, France, St. Bernard (1090–1153) writes poetically, ‘The sick man sits upon the green lawn […] he is secure, hidden, shaded from the heat of the day […]; for the comfort of his pain, all kinds of grass are fragrant in his nostrils’ (quoted in Marcus). St. Bernard cannot articulate a scientific explanation that clarifies just how nature comforts his patients, but there is an acknowledged mystical authority with which his gardens are imbued. The arrival of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, however, marked a decided shift in hospital design and the incorporation of restorative gardens. Clare Marcus, Professor Emerita in the Departments of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at the University of California, Berkeley, notes that monastic centers of medical care declined due to plagues, agricultural disasters, and explosive urban growth, all of which inundated small monastic centers with too many patients. The gradual decay of monasticism in general, writes Sam Bass Warner, Jr., resulted in the demise of the ‘meditative garden […] and open spaces attached to hospitals became accidents of local architectural tradition, if they existed at all’ (quoted in Marcus 7).

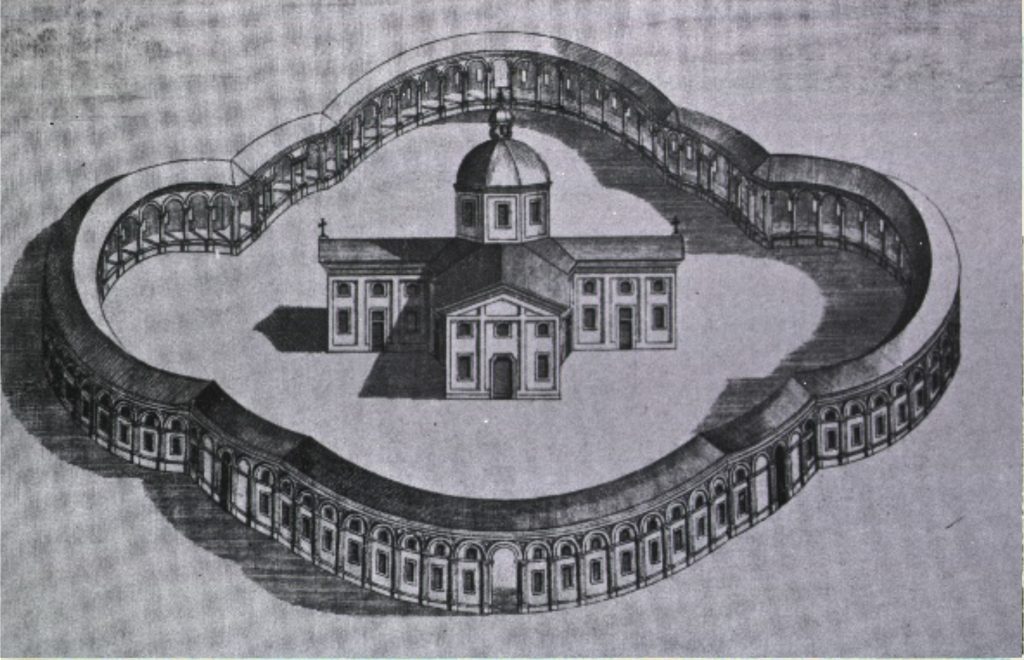

As medical care shifted from individual monastic communities to Roman Catholic civic and ecclesiastical institutions, there emerged perhaps the most salient architectural change in European hospital design. This change, observe Thompson and Goldin, involved building hospitals that mimicked cruciform design, a layout that incorporated elongated halls so that every patient bed was in view of the priest celebrating Mass (Thompson and Goldin 31). Inspiring this design, and others like it, was the Ospedale Maggiore based in Milan, Italy, whose yawning cathedral-like (and strangely panoptic) space placed its windows far above the wards, isolating patients from the green world outside of the hospital.

Courtesy of the U.S. National Library of Medicine

These dim, sacerdotal spaces, shuttered from the warmth of sunshine, were soon opposed in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by the synthesis of two unlikely, but compatible, discourses: scientific medicine and Romanticism (Marcus 8). A main clinical contributor to hospital design modifications was the notion that infections were spread through ‘noxious vapors’ and poor air quality (8). To combat disease-ridden miasma, hospital designs championed building elements that circulated fresh air and facilitated cross-ventilation. The two or three-story pavilion hospital, derivative of the Royal Naval Hospital based in Plymouth, England, thus emerged as the new design in the nineteenth century. The signature element of the pavilion hospital was a colonnade ventilated by a series of large windows (8). In contrast to other church-like layouts, these ‘new designs incorporated outdoor spaces between pavilion wards, while the rise of Romanticism prompted a reconsideration of the role of nature in bodily and spiritual restoration’ (8). These designs were lauded for their pro-hygiene elements, as well as for their renewed emphasis on the role of nature in patient convalescence. Scientific rigor, paired with Romanticism’s emphatic zeal for the human-nature bond, merged to create hospitals with architectural elements that brought patients into direct contact with nature. Florence Nightingale (1820–1910), the nurse and public health reformer, gave a panegyric for the pavilion hospital: ‘[…] the being able to see out of a window, instead of looking against a dead wall; the bright colors of flowers; the being able to read in bed by the light of the window close to the bed-head. It is generally said the effect is upon the mind’ (quoted in Gerlach-Spriggs 16). The pavilion design played a critical role in integrating natural elements in hospital spaces.

Sailors sunning themselves on the rock grotto sun porch

Credit: U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections

The ravages of infections, particularly tuberculosis, and the advent of the pavilion hospital further engendered the assimilation of gardens and outside areas into hospital designs. In the nineteenth and early twentieth century, attention shifted to moving hospital beds and wheelchairs onto sun porches and lawns so that patients could benefit from the restorative sunlight and fresh air celebrated by Romanticism. At this time, too, the design and construction of psychiatric hospitals and asylums included landscape layouts that prioritized the creation of aesthetic views: ‘New asylums were laid out with peripheral grounds and plantings to protect the patients from curious onlookers; landscape vistas were created to provide therapeutic experiences; and grounds maintenance, gardening, and farming became intrinsic components of the therapeutic regimen’ (8). Garden work and floral care, too, were promoted by clinicians. In his 1886 book, How to Care for the Insane: A Manual for Attendants in Insane Asylums, Dr. William Granger writes, ‘Patients should be encouraged to do something for themselves […] The women can add to ward work, sewing, knitting, mending, embroidery, artificial flower making, quilting, care of flowers in the ward, and it is often a real enjoyment for patients to make some little present for their outside friends’ (Granger 35). Indeed, hospital gardens were not considered as only meditative places of convalescence, but spaces that could be collectively maintained and cared for by patients as a form of occupational therapy.

Credit: U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections

Hospital gardens and green spaces were essentially integral to clinical institutions that specialized in providing long-term patient care. A May 1865 article entitled ‘Sanitaria, or Homes for Discharged, Disabled Soldiers,’ penned by Fred N. Knapp, Superintendent of Special Relief (U.S. Sanitary Commission), articulates the goals of sanatoria: ‘Now that the excitement of actual war [the Civil War] is over, and the demand upon the men and women at home for thought, time, money, and supplies for sick and wounded soldiers has nearly ceased, people are turning their attention to the question of how best to provide permanently for those soldiers who have been disabled in the services’ (Knapp, no page number). He continues, ‘The inducement would consist in opening to the men [disabled veterans] the use of workshops, farm lands, gardens, and the like, as well as a play grounds and reading rooms’ (Knapp). Following World Wars I and II, in particular, gardens enjoyed a renewed ascendency in medical care and rehabilitation programs: ‘horticultural therapy programs with special-purpose garden facilities began to be provided in hospitals for veterans, the elderly, and the mentally ill’ (9). Sifting through the voluminous papers of the ‘Conference of Officers in Charge of Government Hospitals Serving Veterans of the World War,’ there is an emphasis on the potential benefits of rural lifestyles for rehabilitative therapy. Under a general order issued by the U.S. Veterans Bureau, entitled ‘Additional Requirements for Neuro-Psychiatric Hospitals,’ one guideline encourages ‘Liberal use of parole for quiet, chronic patients who can live in farmhouses’ (4). Published in 1918 by an anonymous nurse, A War Nurse’s Diary: Sketches from a Belgian Field Hospital, this autobiographical account notes the cherished importance of her war infirmary’s garden: ‘[…] our front garden became a great feature in our life. Three times a week a band played to the patients, beds were brought out in the shade of the trees whilst officers and soldiers visited their wounded friends. Meals were served outside to them, and the staff had a long table under the tree where we took our meals’ (Anonymous 104). Amidst the carnage and chaos of war, the garden served as a makeshift space of tranquility and human interaction, where the comforts and familiarity of home could be, in part, replicated. Again, gardening and a broader nascent notion of horticultural therapy began to take a distinct shape as clinicians thought more critically about how to facilitate long-term rehabilitation for soldiers suffering post-traumatic stress disorders and neurological issues.

After the first few decades of the twentieth century, the pavilion design was rivalled and largely supplanted by its architectural adversary: the high-rise, multi-story hospital (see image to the left). Horizontal spaciousness was replaced by vertical efficiency. A demand for improved, cost-effective hospital services, and various medical-technological advances, soon eclipsed the pavilion design: ‘In acute care hospitals, the design emphasis shifted towards saving steps for physicians and nurses, and away from attention to the environments the patients experienced. Gardens disappeared, balconies and roofs and solaria were abandoned, and landscaping turned into entrance beautification, tennis courts for the staff, and parking lots for employees and visitors’ (Warner quoted in Marcus 9). Further exacerbating the demise of the pavilion design was the budding repute of urban teaching hospitals, whose ‘gardenless patient environments’ set the dominant precedent for other the design of other medical institutions (9). There is a stark similarity between the cruciform regularity of the Ospedale Maggiore and the vertical isolation of the high-rise teaching hospital, both of which severed the patient from any meaningful connection to nature.

Marcus notes that during the 1970s, high-rise acute care hospitals came to resemble ‘air-conditioned office buildings’ whose outdoor spaces were largely limited to flower-lined walkways, entrance gardens, and well-manicured lawns, none of which were intended to be used by patients (Marcus 9). The cosmetically minded layout and isolation of these institutions severed patients from the restorative power of green spaces. These powers, noted the British neurologist Oliver Sacks, are critical not only to patients, but general human self-care: ‘The role that nature plays in health and healing becomes even more critical for people working long days in windowless offices, for those living in city neighborhoods without access to green spaces, for children in city schools or for those in institutional settings such as nursing homes’ (Sacks). Resembling sprawling corporate campuses, hospitals display the trimmings of hotel lobbies and airport terminals—vegetation of any kind, including plastic décor, serves to only cosmetically adorn clinical spaces:

“By the 1990s, insurance companies and hospital administrators competing in the burgeoning “healthcare industry” have generated hospitals that resemble hotels or even resorts, with elaborate entryway landscaping, plush foyers, art-filled corridors, and private rooms. The restaurant in Monterey Community Hospital with domed skylight, interior koi pool, and rattan furniture is so attractive that local business people go there for lunch (9).”

With this kind of design model, plants and gardens assume a largely aesthetic role within clinical spaces, leaving little room for patients to access ‘green’ and other outdoors environments. Fortunately, though, these luxury-type designs have not totally eclipsed gardens at all hospitals—in fact, there are many thriving garden programs that serve thousands of patients every day.

Hospital Gardens & Horticultural Therapy Today

Credit: U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections

If anything has remained constant since the verdant era of St. Bernard’s monastic gardens it is the curiously ineffable influence that green space exerts on human health. Just as St. Bernard remarked on the salubrious energy of his Clairvaux hospice gardens, Oliver Sacks mused, in 2015, just as searchingly: ‘I cannot say exactly how nature exerts its calming and organizing effects on our brains, but I have seen in my patients the restorative and healing powers of nature and gardens, even for those who are deeply disabled neurologically. In many cases, gardens and nature are more powerful than any medication’ (Sacks). The human-plant dynamic was just as gnomic to Ralph Waldo Emerson, who spoke of it as the ‘occult relation between man and vegetable.’

Spanning centuries, neither St. Bernard nor Emerson nor Oliver Sacks could articulate the precise mechanisms that give gardens their restorative powers. Clinical research, however, has elucidated the specific benefits that garden and horticultural therapy have on patients with physical, mental, and neurological illnesses. Recent research, for example, concludes that green spaces and horticultural activities promote social and cognitive wellbeing among elderly patients living in long-term care facilities; visual exposure to plants mitigates patient anxiety and feelings of restlessness (Rappe 37). Another case study examined how horticultural therapy affected participants in an inpatient cardiac rehabilitation program, and concluded that horticultural therapy improved the mood of the patients (Wichrowski 270–274). Joanna Wise’s book-length study, entitled Digging for Victory: Horticultural Therapy with Veterans for Post-Traumatic Growth, examines the therapeutic benefits of gardening for veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome, and how gardening programs can be integrated in rehabilitation programs. Although research reveals the generally positive results of horticulture therapy, it is difficult to collect data that would contribute to larger, more compelling investigations. Generally, practitioners urge more rigorous scientific research that would further legitimize horticultural therapy’s rehabilitative efficacy. Gwenn Fried, manager of horticultural therapy services at NYU Langone’s RUSK Rehabilitation Center, notes that research could be more convincing if it actually measured and monitored patients’ improvements during the course of their recovery: “Researchers need to look for behavioral or progress differences of patients who are participating in a horticultural therapy intervention. For example, does a patient show increases in endurance when working on a planting activity rather than when engaged in a more common physical therapy activity?’ Fried’s colleague, Abby Jaroslow, a registered horticultural therapist at MossRehab’s Alice and Herbert Sachs Therapeutic Conservatory (in the Philadelphia region), also comments: “Studies will have to include larger numbers of patients and include objective, physiological findings, rather than only subjective or anecdotal results. I think it would be especially interesting to see functional brain scans before, during and after horticultural therapy sessions as one possible way of measuring physiological benefits of horticultural therapy.”

Horticultural therapy has yet to take a permanent foothold in American healthcare—and this is, in part, largely due to a lack of institutional awareness of what it is. ‘The greatest barrier to healthcare professionals and researchers taking horticultural therapy seriously,’ remarks Jaroslow, ‘is that they don’t know what horticultural therapy is and they don’t understand how it can be used in healthcare.’ Another challenge is distinguishing horticultural therapy from other established therapeutic services, such as animal and music therapies, in order to demonstrate the singular physiological and psychological effects that plants have on patients. Fried clarifies, ‘Horticultural therapy has been used as a modality for a long time. What is new is the delineation of horticultural therapy as a separate modality.’ What will ultimately help to separate horticultural therapy from other alternative modalities, comments Jaroslow, is clinical research that can ‘show hard evidence to support the notion that access to nature improves outcomes and saves money in the healthcare setting.’

Recent popular interest in horticultural therapy might stir more clinical approaches to studying its benefits. One early example of such an investigation was initiated by the environmental psychologist, Roger Ulrich, whose 1984 Science article argued that access to gardens—even being able to merely see a garden—occasionally accelerated patients’ healing following surgery. Ulrich studied patients recovering from gallbladder surgery. Medical records indicated that patients who recovered with bedside windows recovered a day faster, on average, and required less pain medication than those who had no ‘green’ windows (a scientific echo to Florence Nightingale’s enthusiasm for hospital fenestration). Increased clinical research that demonstrates strong, correlative evidence is needed to further cement the legitimacy of horticultural therapy.

But for what horticultural therapy lacks in the hard empiricism of statistics and neuroimaging it makes up for in memorable anecdotal evidence—human experiences that all seem to reaffirm Emerson’s earthy maxim, ‘All my hurts my garden spade can heal.’ In a recent article, Fried says, ‘“People [patients] can sometimes be a little resistant when you show up with dirt in a hospital, […] And then they’ll participate once, and they’re calling: “Can I have it tomorrow?”’ (Shechet). Fried explains why there is usually a sudden change in patients’ reaction to gardening, ‘In an increasingly technical and unfamiliar environment, plants and nature provide a normalizing diversion. […] Plants live and grow so they provide hope for a future.’ Fried’s patient encounters include working with a woman who, having survived a car accident in which her partner was killed, had difficulty seeing the greater purpose of therapy. But during her time in horticultural therapy, this patient’s doubt was dispelled as she ‘started to see signs of Spring, began to realize that there were things that were still beautiful and wondrous, and started to engage more in life and her therapies.’

Jaroslow, who was inspired to study horticultural therapy following her daughter’s pediatric brain cancer treatment, cites her instructor’s recollection of a story told to him by the director of the Brooklyn Botanical Garden. The day after the September 11 terrorist attacks, she arrived to work to find hundreds of people waiting silently for the garden to open, where they sought to walk and sit in solitude, sheltered from the confusion of the tragedy.

Credit: Abby Jaroslow

Unlike other therapeutic modalities, such as music therapy, horticultural therapy places patients in contact with living organisms that require attention and care. Fried explains, ‘Plants are living and grow and change with time. Plants may provide a metaphor to the cycle of life.’ Although patients may not always be attuned to botanical metaphors and how they relate to their own complex medical conditions, they are given an opportunity to take their place in a cycle of care, of being cared for and of giving care—‘engaging with a living thing, that will thrive under their care, in a non-judgmental, non-verbal, non-confrontational way,’ reflects Jaroslow, ‘can give a patient a feeling of self-worth and hope.’

Special thanks to the following interviewees who contributed to this article: Gwenn Fried (Manager, Horticultural Therapy Services) of RUSK Rehabilitation, NYU Langone Orthopedic Hospital; Abby Jaroslow, HTR, CH (Horticultural Therapist) of MossRehab, Pennsylvania; and Stacy Peeples (Curator-Lead Archivist) of the Pennsylvania Hospital. Unless otherwise noted, images are in the public domain and were provided by the U.S. National Library of Medicine’s Digital Collections.

Work Cited

A War Nurse’s Diary: Sketches from a Belgian Field Hospital. New York : The Macmillan Company, 1918. Pdf. Retrieved from the U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections, http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/01110260R

Conference of Officers in Charge of Government Hospitals Serving Veterans of the World War. Washington, D.C.: United States Federal Board of Hospitalization, 1922. Pdf. Retrieved from the U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections, http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/14230320R

Gerlach-Spriggs, Nancy, Richard Enoch Kaufman, and Sam Bass Warner. Restorative Gardens: The Healing Landscape. Yale Univ. Press, 2004.

Granger, William. How to Care for the Insane: A Manual for Attendants in Insane Asylums. New York: Putnam, 1886. Pdf. Retrieved from the U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections, http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/66440580R

Knapp, Fred N. ‘“Sanitaria,” or Homes for discharged, disabled soldiers.’ Fred N. Knapp, U. S. Sanitary Commission. Washington, D. C., May 5. Washington, 1865. Pdf. Retrieved from the U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections, http://resource.nlm.nih.gov/101156142

Marcus, Clare Cooper, and Marni Barnes. Gardens in Healthcare Facilities: Uses, Therapeutic Benefits, and Design Recommendations. Concord, CA: Center for Health Design, 1995.

Rappe, Erja. The Influence of a Green Environment and Horticultural Activities on the Subjective Well-Being of the Elderly Living in Long-Term Care. 2005. University of Helsinki, Department of Applied Biology dissertation.

Sacks, Oliver. “Oliver Sacks: The Healing Power of Gardens.” The New York Times, 18 Apr. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/04/18/opinion/sunday/oliver-sacks-gardens.html. 18 June 2019.

Shechet, Ellie. “Heal Me With Plants.” The New York Times, 25 Mar. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/03/25/style/plants-hospital-horticulture-therapy.html. 9 May 2019.

Thompson, John D., and Grace Goldin. The Hospital: A Social and Architectural History. Yale Univ. Press, 1975.

Ulrich, Roger. “View Through a Window May Influence Recovery from Surgery.” Science, 224, 1984, pp. 420–421.

Warner, Sam Bass Jr. “Restorative Gardens: Recovering Some Human Wisdom for Modern Design.” Unpublished paper, 1995.

Wichrowski, Matthew, et al. “Effects of horticultural therapy on mood and heart rate in patients participating in an inpatient cardiopulmonary rehabilitation program.” Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention, vol. 25, no.5, 1996, pp. 270-274.

Wise, Joanna. Digging for Victory: Horticultural Therapy with Veterans for Post-Traumatic Growth. Routledge, 2018.