Editor’s Note: This is the third of four installments from guest blogger Dwai Banerjee, a doctoral candidate in NYU’s department of social anthropology. Images illustrated by Amy Potter, courtesy of Cansupport.

Part III

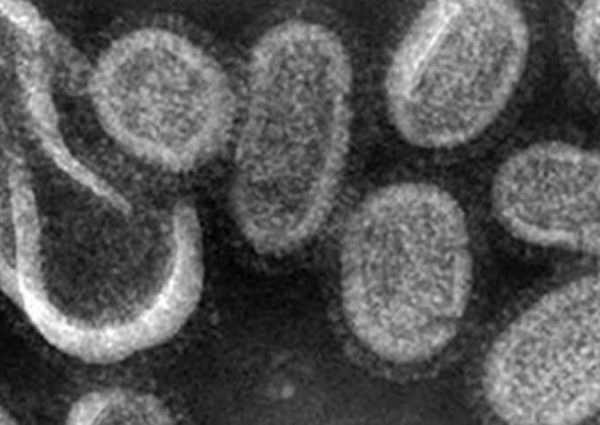

In a later visit with the homecare teams, I met Rajesh – a 29-year-old man who has been battling cancer since his teenage years. The walls of his room in a dense middle-class neighborhood were bare but for two pictures – one of a Hindu deity and another of his parents who had passed away in an accident when he was still young. Rajesh had contracted cancer while working in a chemical factory in his late teens. The cost of his treatment led him to lose the little property that his parents had left him when they had died. The relatives that he lived with now took him in, but refused to extend any form of empathy or care. The stigma of the diagnosis of ‘cancer’ along with fears of its communicability saw to his isolation in the small verandah of the house. Yet, Rajesh’s will to live was strong; on his own, he would travel to the All India Institute for Medical Sciences (AIIMS) early in the morning, negotiate the intricacies of the bureaucratic processes and make himself available for treatment.

As it stands, effective public health insurance is by and large absent in the Indian health scenario. In its place, the only financial respite for the poor comes in the form of subsidized treatment at government facilities. The bureaucratic procedures involved in procuring these government grants are daunting at best; very few cancer patients are able to transact the opaque bureaucratic process within the time allowed by rapidly progressive malignancies. Fortunately in Rajesh’s case, where kinship had failed, a local network of knowledge and care stepped in. Cansupport and a sympathetic AIIMS doctor collaborated together to procure both a part-time nurse to care for Rajesh, while also taking him through the process of applying for a set of government grants.

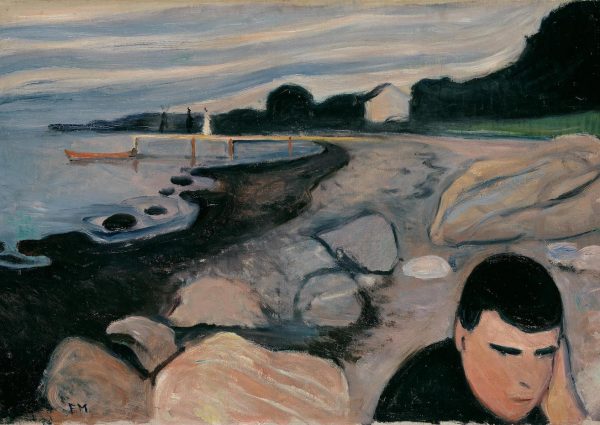

In my conversations with Rajesh, it became clear that the years battling both the disease and the public health system and spent him. Time and again, his upbeat demeanor would collapse; at the end of one of our conversations as I made to leave, he stated baldly that if the disease returned he would not fight it again. It had deprived him of years of income and left him at the mercy of a family that had not cared for him at his most vulnerable. He had become the errand boy of the locality, earning his room’s monthly rent by doing chores for his family and neighbors. His resentment towards his family was something that he had been forced to learn to hide; working for them allowed him to transact the complicated business of ‘living on’ with the disease. Over the next few weeks, Cansupport would try and work with its funders to set Rajesh up with a food-cart, to gain him the monetary security and independence he needed. While the biology of the disease was now in remission, the collapse of the infectious life of cancer had spread outside the body, jeopardizing his will and ability to carry on.

Dwaipayan Banerjee is a doctoral candidate at the department of social anthropology at New York University. Prior to his doctoral candidacy at NYU, he graduated with an M.A. and an M.Phil in sociology from the Delhi School of Economics, India. He has recently completed ethnographic work concerning the experience of cancer, pain and end-of-life care in India. His research follows the circulations of these experiences across different registers – language, medicine, law and politics. His broader interests includes working at the intersection of philosophy and anthropology, as well producing and studying ethnographic film and media.