Marianne R. Petit

Associate Arts Professor, Global Network

Associate Arts Professor

Associate Vice Chancellor for Global Network Academic Planning

Marianne R. Petit is an Associate Arts Professor at NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program and the Interactive Media Arts program at the Tisch School of the Arts. She co-founded the original IMA Program at NYU Shanghai in 2013 and held a joint appointment between the two campuses for several years. Additionally she serves as an Associate Vice Chancellor for Global Network Academic planning, with a focus on teaching and undergraduate global curriculum development.

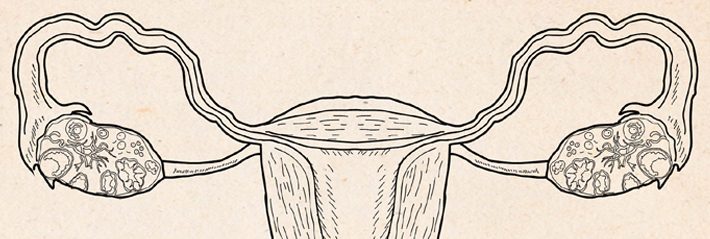

She recently launched a project entitled “Our Hysterectomies”, a 72-page eBook containing the illustrated first-person accounts of 16 women (herself included) who have had hysterectomies, oophorectomies, myomectomies, and more. The eBook also contains animation, as well as printable DIY paper craft.

Personal narrative is a focus of your work.

How would you define it?

How is a different than biography?

Are there parallels to narrative medicine?

The autobiography chronicles an entire life whereas personal narrative focuses more on specific events or experiences and the context, connections, and reflections that surround them. The form may be written, as with autobiography, but personal narratives take a myriad of expressions and allow participants to experience the storytelling in a rich way. I think there are definite parallels to narrative medicine, which looks beyond an individual’s clinical or medical experiences to address the broader emotional and relational contexts. In both, we see the creative expression of individual stories to shed light and understanding. I see both as creating potential for empathy and compassion.

Can you tell us about your research and work methods. especially elements you use for crafting the narrative, combining medical knowledge with your personal story?

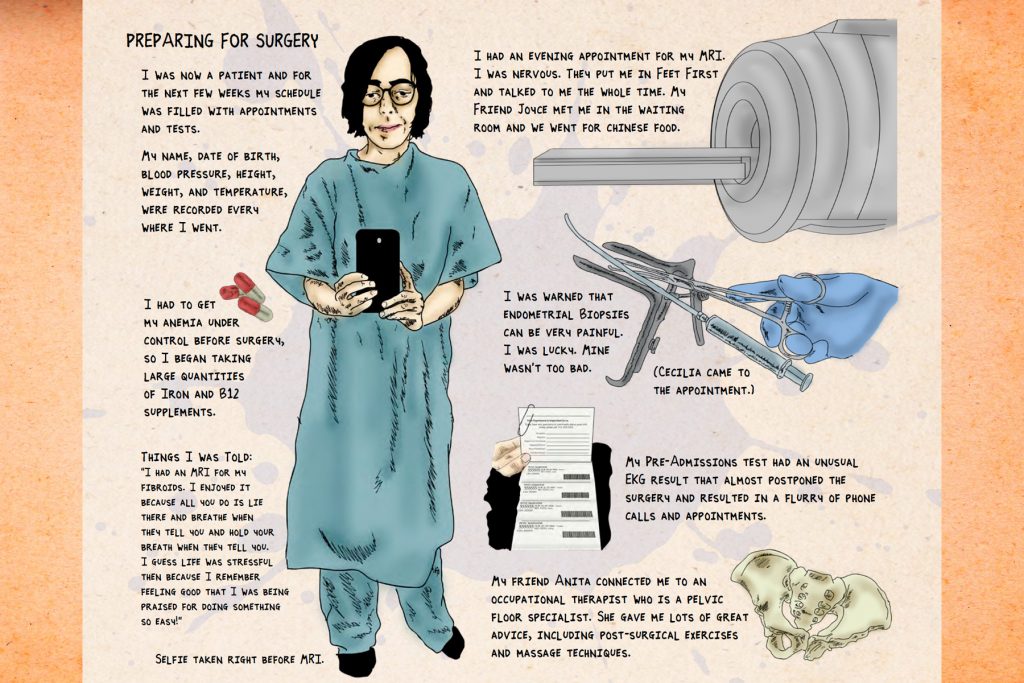

In 2010 I decided that I didn’t want to be a professor anymore so I enrolled in nursing school. For two years I taught by day at Tisch and attended preclinical courses in the evening. The coursework was difficult, but I loved it. In the end, I never completed my studies because I moved to Shanghai to launch an undergraduate program, but my interest in the human body remains. Looking at medical illustrations and photography is something I find very satisfying and do with some regularity. As a result, that was a continuous process for me, both during my own procedure and through the making of the book. One thing I loved is that several of the participants felt comfortable sharing photographs of their tumors, surgical scars, and bruised bodies with me.

As for telling my own story, that was a separate but also familiar process. I continuously take photos and write notes so as to not forget. I am always amazed at how a single photograph or a short captain’s log entry can bring back a flood of memories I would otherwise lose. So, as events were unfolding I jotted everything down and took photos. I wrote the first draft three months after surgery while everything was still fresh in my mind and then put it away for nearly a year.

On a personal level, was it empowering writing your own story and putting it out in the world?

What kinds of reactions do/did you get?

The first time someone asked me if it was empowering to write my own story I was genuinely surprised because telling my story came from a position of empowerment.

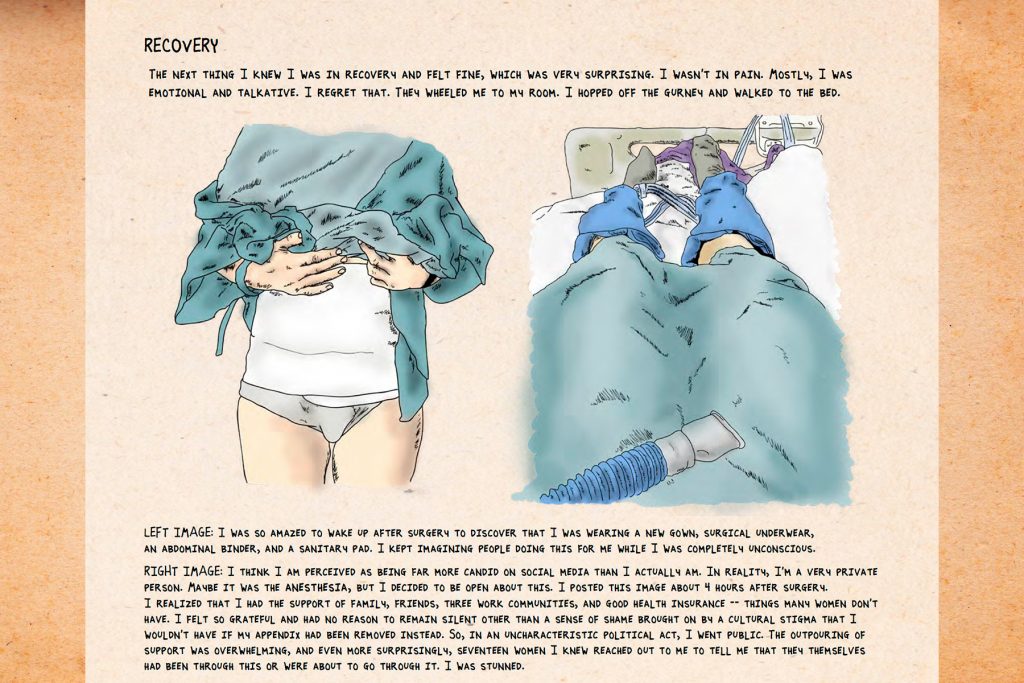

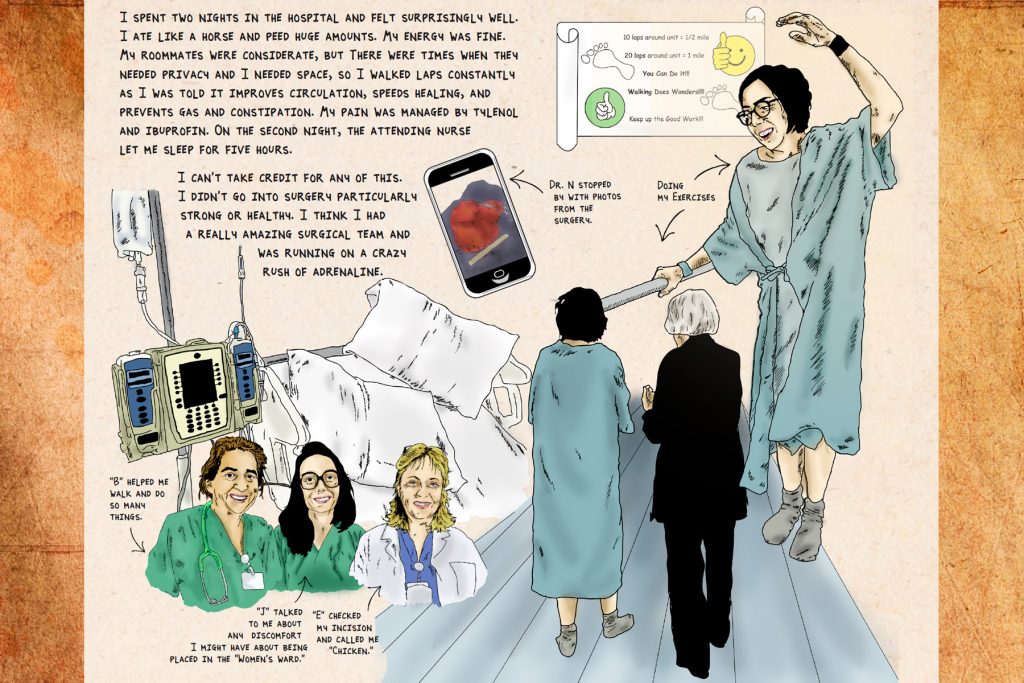

Prior to my surgery, several friends and colleagues shared their experiences with me, however, they were very private about it. They didn’t feel safe being public and for good reasons. However, as I describe in the book, upon waking up from surgery I felt surprisingly well. I hopped off the gurney, walked laps, and ate two dinners, and while I am typically rather private, I decided to be open about this. I had access to good health insurance, excellent medical care, and the support of three work communities—privileges many women don’t have. I felt no reason to remain silent other than a sense of shame brought on by a cultural stigma that I wouldn’t have had my appendix been removed instead. And so, in an uncharacteristically public political act, I posted an image of myself from the hospital on social media. The outpouring of support was overwhelming, but even more surprising, seventeen women I knew reached out to tell me that they had been through the same thing, some only weeks earlier. I was stunned, and began to reflect on the stories that induce our silence and the fictions we present instead.

As an artist I’ve drawn from personal experience and have made self-portraits for years, so telling my story was easy. However, it was only after sharing my story that I felt vulnerable. There were moments when I realized that everyone knew this thing about me. Healing in public and the sympathy of others, however well meant, can be alienating. I was forced, at times, to process the discomfort of others. But I concluded that in sharing my story from a position of strength, I could absorb the fear and discomfort of others and that perhaps this could contribute to a collective and more compassionate understanding.

How did you reach out to other testimonials and what were the guidelines for participation?

I reached out to everyone who had personally shared their story with me to see if they would like to share it in the collection. Their responses were extremely diverse. For some, it was an easy “yes!”, for others a definitive “no!”, and others needed to think about it. I didn’t provide guidelines. It was obvious that everyone’s experiences were so deeply personal,I didn’t want to inhibit their expression. I felt it was important that everyone be represented in the manner in which they felt most true and most at ease with.

Some wrote essays, while others wrote letters, journal entries, or catalogued email correspondence. Some provided photographs, while others asked me to do whatever I wanted visually. Others wanted to tell their stories through their own comics, drawings, and photography, which I also loved. Some individuals used their own names, while others used a pseudonym. And while some were very happy to have a visual representation of themselves, others wished to have no identifying characteristics. It was clear everyone’s relationship to their story was unique, and everyone’s story in relationship to their world held a position that I had to respect.

Why is personal narrative important?

I think we’re living in a time where everyone is continuously publishing their personal stories online, but our presented versions are tremendously curated. As a result, our streams are filled with people apparently living glorious lives that we’re not experiencing. The impact of those constant stories to our handheld devices can feel so damaging. Most of our lives are filled with mundane moments and genuine struggles, which in contrast to our feeds make us feel like we’re on the margins and some how failing.

The problem is that the range of acceptable or comfortable stories only grows narrower while the bulk of life and truth falls increasingly in the margins. Yes, we may know intellectually that everyone has struggles that they aren’t sharing publicly, but we also see just how uncomfortable others can become when individuals share those stories. Our collective discomfort only serves to alienate a person who is saying things we don’t want to hear or who is perceived as “over sharing”. This, unfortunately, only serves to push more of us into silence and bolster a particular privileged narrative.

So, I believe that sharing our personal narratives is critical. Yes, telling those stories may make some uncomfortable, but the courage of another person’s truth can give us space to reflect upon and connect to both their story and our own.

To summarize if you can briefly describe your future/ current projects and how crafting this work might have influenced your process?

I typically describe my work as “exploring fairytales, anatomical obsessions, and collective storytelling practices through mechanical books that combine animation and paper craft.” This project certainly hit several of those points. Working with the women who participated in this project has also only made me want to engage in this further. I am currently working on several projects (to be launched 2019-2022) and consequently reflect daily on the power of shared narratives and the relevance of storytelling to our current times. These projects range from a pop-up adaptation of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Wild Swans” to an illustrated anthology entitled “On Murder, Forgiveness, and Perpetual Sorrow”, which chronicles first-person accounts of individuals who have been affected by murder and its consequences.

Marianne R. Petit Website

Our Hysterectomies

Download links for the full ePub and interactive pdf formats of the book

Google Drive or DropBox