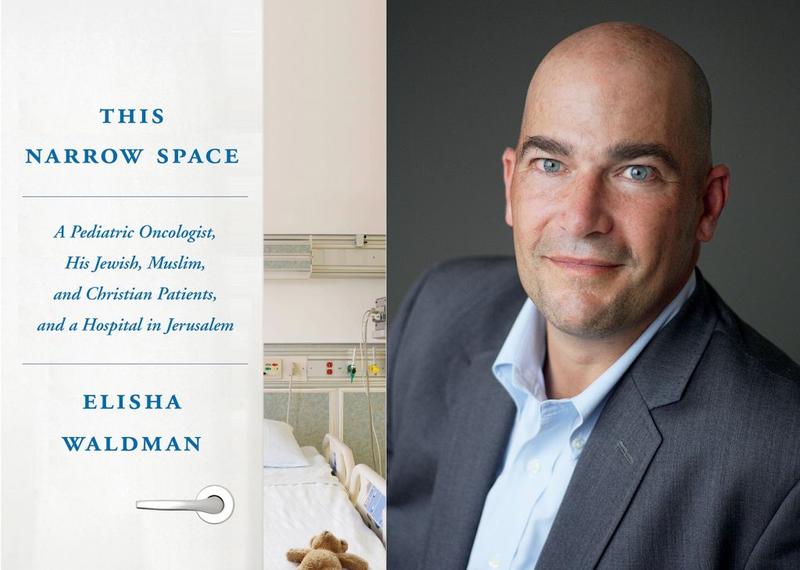

The following is the edited transcript of an interview with Elisha Waldman, MD, author of This Narrow Space, a memoir of his time working as a palliative care physician in Israel. In the book Dr. Waldman writes about his time working as a pediatric oncologist at Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem, treating Israeli and Palestinian children.

Dr. Waldman is currently the Associate Chief, Division of Pediatric Palliative Care, at the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago, and is Assistant Professor of Pediatrics (Palliative Care) at Feinberg School of Medicine of Northwestern University.

Dr. Waldman’s writing has appeared in Bellevue Literary Review, The Hill, The Washington Post, The New York Times, and Time. This Narrow Space is his first book.

Steven Field, MD is a Clinical Assistant Professor of Medicine at NYU School of Medicine and Associate Faculty, Division of Medical Ethics, Department of Population Health, NYU School of Medicine. Dr Field is also a Clinical Ethics Consultant at NYU Langone Health.

Steven Fields: Thanks so much for joining me today for this interview. While I have several questions, I’m going to start with a very specific one that draws on a point you raised in the book: How did you wrangle with the question of theodicy?

Elisha Waldman: This book was percolating in me for years, probably for decades before I sat down to write it. And the book that was percolating was a book about theodicy in the context of my experiences as a clinician, and elements of that were bled out of it to make it more appealing to the general public.

SF: You mentioned that you were a religious studies major in college. Especially as a son of a rabbi, how did you go from religious studies to medicine?

EW: In retrospect, it makes sense and it all fell into place. I did not always know I wanted to be a doctor, but I always had an interest in possibly pursuing medicine. I wasn’t one of those driven, got-to-be-a-doctor types, and frankly, by the end of undergraduate [school] I thought I was going to go on and get a PhD in religious studies and spend my time thinking about philosophy and theology. The medical studies were, for me, a vehicle for spending time in Israel because that had also been a big part of my life. It seems absurd but I really thought I was going to do that for four years and then go back to Harvard Divinity School. It was only [during] the third year of medical school when we got into the wards that I started to say, there’s something to this; this appeals to me. It struck a chord because no one specializes in pediatric oncology and trains at Sloan Kettering unless you’re driven to some degree. But I think it didn’t click into place for me until I started practicing palliative care. I think it was only mid- medical career that I could look back and see that arc and say, I see where theology and the humanities and medicine come together. And in a weird way it’s only now at 46 that I’m embarking on the part of my career where I am where I’m supposed to be.

SF: In your work you have to deal not only with physical pain, but also existential suffering.

EW: Exactly. I was just rereading Eric Cassell’s classic, The Nature of Suffering and the Goals of Medicine, which I read from time to time because it speaks to me at different stages. He writes so beautifully about suffering. As you point out, it’s not pain–”Oh, I’ve got a broken bone”– but suffering [is really something that] is experienced by the person, by the human being. At least when I was trained, we weren’t trained to get at that. When people ask what palliative care does, I like to think that what we do in palliative care is address suffering, like cardiology focuses on the heart and nephrology on the kidney. Hopefully we address it and alleviate it as opposed to observe it, although sometimes the job is to observe.

SF: Have you gone back to visit Hadassah Hospital? Are you in touch with any of the people who are still there?

EW: I still have a deep love for the department, and I’m still close to Fatimah [one of the nurses at Hadassah that Waldman worked very closely with]. She’s an interesting person. I think her historical experience as an Israeli Arab working within the Israeli medical system with Palestinians is such a fascinating existence.

SF: To be in a hospital taking care of two different segments of the population, who at least politically are at war with each other most of the time, or at least that’s the perception that we have over here: when, for example, someone like Fatimah is working there do people consider that she’s working for “the enemy?” Or conversely, do some of the right wing Israeli patients or clinicians view you that way in terms of taking care of Palestinian children, Arab children?

EW: The answers to your questions are yes and yes. It’s a very complex environment. I think one of the beauties of the department is that we really created a bubble there, and there are moments that I mention in the book, that the tension bubbled up. Actually, when there was war going on outside. But I think everybody, regardless of ethnicity or political persuasion, really did come together for the most part to create a protected environment for the children and families. I’ve thought about it a lot since moving to Chicago a year ago because this is a new environment for me, but my impression is that this is a divided city in ways that may seem less overt than in Jerusalem, where there’s a wall, but a lot of the same issues translate back here. We’re still dealing with issues in Chicago, and I suspect in many parts of America, where there’s one side of town the other side won’t go to. You have a disenfranchised population that has to come into our health system for help, and there’s a lot of mistrust going on there.

SF: I’m wondering whether the bubble at Hadassah that created that safe space is really because everybody is united by the fact that the kids are so sick, that people are able to put aside partisanism.

EW: I think there’s something to that. If there’s one thing that you should be able to come together around in this horrible world we’re living in right now, it’s kids suffering from cancer. It’s very hard to look at a kid suffering from cancer and impose your prejudices from outside against that child.

SF: There’s one moment in the book when a Palestinian child had died and you went to visit the family afterward. And the mother said to you, Come, come, say goodbye to your friend.

EW: That actually was in Boston, but it was an Arab child.

SF: That was quite a moment.

EW: I appreciate that. I use that story sometimes when I teach residents and I kid you not, to this day, in the moment of retelling that I get very choked up. It was a very powerful moment in my medical career.

SF: I imagine that most readers get choked up there too. You describe in the book, in the beginning, this being sort of your Zionist dream, to go to Israel. Moving back to the US must have represented a sort of a sense of it not working out?

EW: When I went back to Israel after doing my palliative care fellowship, I felt almost a messianic sense of rightness, that I was doing the right thing at the right time in the right place. That may not have been such a healthy emotion, although it felt good because of the fact that my whole family made Aliyah and everybody’s still over there. Moving back to the states was really soul-crushing for me and really felt like a defeat. I still miss it greatly. In the interim, in the last four years I’ve gotten married and have two little boys now. I think something about that experience of finally creating my own family has mitigated the whole thing and has allowed me to make a little more sense out of [it]. I’m able to give my kids a life that I think is meaningful and important for them. But I do miss it.

SF: I’m curious about your writing. How do you write and what made you interested in writing?

EW: That’s an interesting question. I’ve always been a reader ever since I was a toddler. I’ve been a voracious reader and I suppose somewhere in the midst of all of that voracious reading, I’ve always had dreams of writing. To be honest, part of how this book happened, which was really a stroke of tremendous luck, [was] through one of your colleagues at NYU. I wrote a short essay about being a physician in the Middle East and in Jerusalem, and I’d originally written it with the thought that I would send it to the Journal of Clinical Oncology as one of these art/medicine type pieces. And in the moment before I submitted it, I said, you know, I’ve always felt like I [would be] far more proud of writing a piece for The New Yorker and maybe I should send this to a literary journal. So I sent it instead to the Bellevue Literary Review. And it got picked up. It took runner-up in their annual contest and from there an editor at Random House happened to read it and reached out to me. And by that time I had actually been thinking about sketching out a whole book project based on that essay, which became the basis for one of the chapters in this book. And so I guess I’m answering two questions at once, both the medical question of what got me interested in writing and then the actual practical, how it happened. I think I’ve always thought about it and never dreamed it would happen. And then I just got ridiculously lucky and stumbled into it.

SF: Have you done any more writing?

EW: I wrote a bunch of Op-Eds last year. I got interested in more short form work and more interested in what impact can we have writing sharper public-facing pieces about our medical field. I am slowly but surely putting together a second book project, which has been slightly delayed by the birth of my second son three months ago. It’s less memoirish and Israel-oriented and more oriented towards parents and children and decision making,

SF: Any desire to write fiction?

EW: It’s crossed my mind, but it’s such a different beast that I think it would require a really conscious decision on my part to try to exercise those muscles. A close friend and colleague of mine, Chris Adrian, writes fiction; he’s actually a well-known writer, and he’s now a palliative care doctor at LA Children’s. And we’ve chatted about it. He writes fiction that I think gets at the heart of what we do, but it’s a very different beast from nonfiction. I think at this point I’m still using the nonfiction writing to exorcise–in the sense of getting out of my soul–some of my own experiences and quandaries, and that’s really what drove this book. And I’m not sure how I would do that in fiction although clearly people do manage that.

SF: Have you ever done any structured training, pursued an MFA or taken writing workshops?

EW: I did writing workshops. When I was a fellow at Sloan Kettering now and then I would do the Gotham Writer’s Workshop types of courses which I really enjoyed and [of course] that’s fiction. I still have a stack of short stories that I wrote and never did anything with from them. I think that when I was an oncology fellow was the first period of time where it occurred to me that maybe I could do some writing. Even though the courses that I took were mostly in fiction, I think it’s shaped how I read and therefore how I think about my own writing.

SF: What are you reading now?

EW: I’m between two things. To give you a sense of my eclectic taste, I just finished Up with the Old Breed, which is a first person memoir of a US marine in World War II in the Pacific. Don’t even ask how I got into that. A very intense but interesting read. And now I’m splitting my time between a fiction book and a nonfiction book. I’m reading, really rereading, a really cool history of modern art, which I both find interesting in and of itself, and also because I think that it informs a lot of how I am looking at patients and thinking about patients, and that’s interspersed with a French novel in translation, HHHH, which I just started, which is a novel about the assassination of an SS officer in Czechoslovakia in WWII, a true story.

SF: Reinhard Heydrich?

EW: Yes, it’s about the assassination.

SF: Sounds like you keep very busy on the pleasure-reading front. In your work, other than what you write yourself, are you involved in any medical humanities programs in the hospital?

EW: Very much so. At each stage in my career I’ve always had some elements of humanities teaching be a part of my job. At Columbia, I taught a course two years ago for Rita Charon; I have an interest in spirituality in medicine, so I taught a course for her in that. I’m actually in the process of trying to recreate a similar course here for the medical school, which hopefully will launch in the winter, on spirituality in medicine, and I find that a lot of my time teaching residents now focuses more on the humanities side. I gave Grand Rounds last Friday and there was not a single slide in the entire talk that contained any text. It was all paintings, photographs, discussion of my own experience and how that feeds into patient care here. So I would say that in that respect, you know, I try to bring the humanities to the bedside every day for the residents.

SF: That’s terrific; and critically important these days. I’m curious; there has been a lot of talk recently about shortening the duration of professional education; three-year medical school, and of course—which is nothing new—six year combined bachelor’s and medical degree programs. Do you have any opinion about that?

EW: It’s interesting. I couldn’t comment on the medical school aspect. I don’t know the difference between three years and four years. I certainly think that shortening a liberal arts education or shortening an undergrad education is a shame. My wife and I debate this all the time because she’s European and my brother-in-law is a doctor in London so we compare experiences. I think that there’s nothing more wonderful than being able to have four years to explore any subject without regard for what you may end up doing in your career. I look back now and I’m so grateful for the time spent in religious studies, which clearly has an impact on what I do today, on time spent in art history courses, which I believe also has an impact on how I practice today. I took a lot of literature, Russian literature; all of it makes you a richer human being. And that’s what we need at the bedside, right? Now you’re going to get me going on my whole riff about how our American healthcare system has just bled the soul out of medicine. I tell the residents here, if you don’t stop to understand the narrative, if you’re not stopping to understand who your patient is, what their story is, what their context is, then you’re just working in a factory.

SF: You’re preaching to the choir here. I believe that not only are you just working in a factory, but you also miss the fun.

EW: Absolutely! I a hundred percent agree. I gave the residents this talk just last Friday. I said people look at what I do, not just pediatric oncology, now palliative care across the hospital, and what could be more [depressing]? And people ask me how do you do it? It must be terrible. And I had two patients die last week who I was close with and very involved with. And the answer is, I love it, and it’s not to say that it’s not sad sometimes, or that I don’t come home totally tapped out sometimes, but I come home fulfilled. I come home feeling that I have done something with meaning. Last Friday I was at the end of two weeks on service that were just brutal and, Friday afternoon, right when I wanted to just sign out and go home, have a beer and relax, finally, after two weeks, we have this complicated family meeting set up at 4 in the afternoon with multiple teams and the family of a kid with a terrible underlying condition. And I was cranky, and I whined about it. I tried to get the meeting moved earlier, and in the end, of course I had to suck it up because I was still on service till 5:00. And I went to the meeting. It was so meaningful because the way things unfolded. It was so important that I, or at least someone from my team, was there. We were able to help the other teams navigate a complicated conversation with a family as they received a lethal diagnosis for their child and started to think about how things might unfold. And it was just so meaningful to be there for a patient who was an immigrant from another country, which just added, especially in our current climate, added another layer of meaning for me.

SF: Right. I would imagine that in palliative care, what you don’t necessarily have all the time in longitudinal follow-up, you have in depth and intensity of the individual encounters.

EW: Yes. it’s wonderful. I love my job. Again, not to say I’m not exhausted sometimes, but, I am certainly not one of these physicians who’s going to tell my kids, oh, don’t go into medicine.

SF: And so, to close the circle a bit her, what about theodicy?

EW: I was waiting for you to circle back to that. My answer is I don’t have an answer. I know that there are people who feel like they’ve come to some sort of an answer. I guess that’s the challenge in life, right, for everybody to figure out how to make meaning. I think over the last 10, 11, 12 years since I consciously set out to try to think about this, at times I felt like I got closer to an answer. I got very interested in process theology. What does it mean to have a God? Because I personally do still consider myself a person of faith. But what does it mean to believe in a God who may be limited, which is a bit of an intellectual mind bender. I think what it comes down to is, I don’t know what the answer is. It’s going to sound corny to say [this], but the journey is the destination. I think that my life has become much richer simply by incorporating engagement around this puzzle into my daily life. I do think that one of the things that was challenging to me or that bothered me about it at the start of my career as an oncologist was [that] I don’t think I thought about it consciously, day-to-day, and then it would sort of rear its head every time a kid died or every time I saw kids suffering. I would go home and say, well, how the hell does this make sense with what I was raised to believe? And I think in the last decade or so, I’ve been engaged in a more conscious practice of what does this mean on a day to day basis. And again, I don’t know if all this sounds wishy-washy and evasive, but I just think the act of being engaged with the mystery has made my life richer. And yes, I would love to know an answer. Although, part of me feels like if we have the answer to all the mysteries in life, I’m not so sure how interesting life would be.

SF: I don’t remember the exact saying, but it’s something on the order of “faith is the ability to believe when there is no answer,” or something like that.

EW: My dad said that. My dad and I had this conversation about courage once in the context of my patients. And he said, you know, courage isn’t doing something difficult. It’s doing something where you know the odds are pretty much against you and, and it doesn’t look like you’re going to succeed. That’s what real courage is: being able to put one foot in front of the other, in the face of that.

SF: I guess sometimes the end of the journey is actually secondary. The journey itself is the experience and that’s the best we can do. OK, so lastly, if you were going to recommend a book to physicians, to young doctors coming up, what book stands out for you?

EW: My personal favorite books that I go back to over time are frankly Moby Dick and The Brothers Karamazov. Those aren’t necessarily books that I would recommend to a young clinician, although they both speak to many of the great mysteries of the human spirit and of our relation to the divine. The truth is, for young clinicians, I have a handful of short stories that I tend to turn to. That may be a function of what you can get medical students and younger trainees to read and digest, because if you hand them a novel, it’s not happening. Chris Adrian, who I mentioned [earlier], wrote a short story in the New Yorker called “A Tiny Feast,” which I use to teach trainees. I won’t give it away, but it’s a brilliant imagining of a blend between pediatric oncology and Shakespeare and fantasy. It’s worth looking up. Every time I read it I get something new, but I think that it speaks to both the experience of the clinicians and the experience, especially, of parents of sick kids. It fascinates me every time I read it, that he manages to get at the heart of those truths through something so fantastical and fictional.

SF: Have you ever read Lorrie Moore’s “People Like That are the Only People Here?”

EW: Of course. That’s a classic. That’s a great one. There’s [also] another one I use. There’s a writer, Aleksandar Hemon, who’s a young guy. I think he lives in New York now. He writes primarily nonfiction short stories. He used to live in Chicago and he also has a short story that was published in the New Yorker called “The Aquarium,” which I use for residents. It’s about the death of his own child of a brain tumor. And it’s interesting when I use it now because it occurred in the hospital that I’m working in, and some of the players that he mentions are still here. But it’s similar to the Lorrie Moore.

SF: OK, then, I think we can wrap up. Any further comments or a closing statement you wanted to make?

EW: No, it’s nice to hear a kindred spirit. I think I’ve said everything. I consider my statement about the need to keep humanity at the center of what we do in medicine—and the role of literature in helping to do that—to be critical.

SF: Great. Well, I really appreciate your time; thanks so much.