By Sebastian Galbo

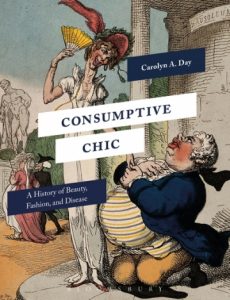

Unique to fashion’s allure is its mercuriality. Tastes and styles change and evolve in constant flux; what’s prosaic today might be elevated and imaginatively transformed tomorrow. Certain historical instances demonstrate, however, that fashion has been more than a material theatre concerned with eye-catching cosmetics and frills, but an important cultural venue that registers and responds to anxieties specific to historical periods beset with certain conditions that provoke fear and uncertainty. Professor Carolyn Day’s recent book, Consumptive Chic: A History of Beauty, Fashion, and Disease (2017), focuses on a peculiar trend of fashion that, spanning from 1780 to 1850, responded to the menace of tuberculosis. This intractable illness mystified physicians; defied conclusive research; with equal force, traversed social classes; and spurred quackery, controversy, and a range of bizarre ‘cures.’ Unable to be medically understood in the fullest, the tubercular body was constructed culturally as a source of special–and sometimes enviable–affliction, giving way to romanticized and aestheticized notions of its symptoms as ideals of beauty. Day’s research captures the complexities of European fashion at a moment vexed by medical uncertainty.

Carolyn A. Day is an associate professor of history at Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina, where she teaches courses in modern Europe and the history of Western medicine. Our Email interview-correspondence took place over the course of a week in March 2018.

Carolyn A. Day is an associate professor of history at Furman University in Greenville, South Carolina, where she teaches courses in modern Europe and the history of Western medicine. Our Email interview-correspondence took place over the course of a week in March 2018.

Please describe your academic background and current research interests.

I must admit I took a bit of a circuitous route to my chosen profession. I started my academic career in microbiology and really had no intention of becoming a historian. I received my B.S. in microbiology and a B.A. in history at Louisiana State University. However, by my junior year it was clear that although I had thoroughly enjoyed my research on cystic fibrosis, once that project came to an end there wasn’t another project that I felt as passionately about. As I began to investigate my other interests, I was fortunate enough to be able to bring together my love of science and history by pursuing an M. Phil in the History and Philosophy of Science and Medicine at Cambridge University and then a Ph.D. in British history at Tulane University.

My research interests lie in the area of lived experience, particularly with respect to illness. For instance, now that Consumptive Chic has been put to bed, I am working on 2 other book projects. The first is a microhistory that investigates the eighteenth-century connections between the mental and physical and the ways in which illness was used as a mechanism for casting blame and exacting revenge. The second project seeks to uncover the experience of invalidism in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Even today, there are social expectations and performative behaviors expected of those suffering from chronic or terminal illnesses. In this project, I am interested in looking at one person’s illness, from the individual’s perspective, that of family and friends, as well as that of the physicians in charge of the case.

In the book you ask, “How is it possible that a disease characterized by coughing, emaciation, relentless diarrhea, fever, and the expectoration of phlegm and blood became not only a sign of beauty, but also a fashionable disease?” Describe how you arrived at this question.

I actually stumbled onto this notion while studying at Cambridge. I kept running across references to tuberculosis being an easy or beautiful way to die, which seemed out of character with my scientific understanding of the illness and left me intrigued enough to investigate further.

What specifically gave rise to what you term the “tubercular moment”? Why were the venues of literature and fashion particularly suited to reflect middle- and upper-class medical anxieties?

Between 1780 and 1850 there was a growing correspondence between tuberculosis and rapidly changing concepts of beauty and fashion. During this period, the dominant presentation of tuberculosis was that of a disease characterized by attractive aesthetics. This was made possible, in part, by a congruence of factors including disease mortality, advances in the approach to illness, and the influence of the key social movements of the era. The cultural expectations that developed for tuberculosis, as a result of these broader changes, were articulated in medical treatises, literature, poetry, and the works that sought to define fashion and the female role. There was a persistent and influential idea during the period that consumption, in its middle and upper class incarnations, was a disease that was not only identified by the existence of beauty in women, but one that also conferred beauty upon its sufferer. Thus, tuberculosis was rationalized as a positive affliction for women, one to be emulated in beauty ideals and fashions. Yet there was also a contradiction, since fashions and the way of life of fashionable society were thought to “excite” the disease in upper and middle-class women who possessed a predisposition to consumption and whose inherent feminine character rendered them more susceptible to the activation of that predisposition. The positive associations with consumption and its “look,” permitted the widespread flouting of admonitions against the clothing and fashionable practices believed to cause the disease.

You acknowledge that clinical uncertainty gave rise to quackery and nostrum-peddling opportunists by citing one memorable medical charlatan, John St. John Long, whose ‘treatment’–which involved applying harmful corrosives–infected and killed a tuberculosis patient. Just how rampant was medical chicanery during this period?

Consumption was not unique in being a venue for quackery, and in a consumer driven medical marketplace there were opportunities for entrepreneurs of all sorts. For an overview, Roy Porter did a study of the subject called Quacks: Fakers & Charlatans in English Medicine.

What astonished you most during your archival research for this book? What jolted the assumptions, expectations, or predictions you brought to this project?

What really surprised me was the longevity of the phenomena and the ways it pervaded so many aspects of life and society. When I first began investigating the topic, I believed it would be a project covering only 10–20 years, but was I ever wrong! The further I got into the research the more I realized that, despite the changing fashions, the connections between beauty and fashion in the middle- and upper-class discussions of the illness covered more than eighty years.

Your study seems to dwell disproportionately on upper- and middle-class experiences of tuberculosis at the expense of capturing the realities of lower social tiers. To be fair, however, you trace how the tubercular moment shaped literature, styles, cosmetics, and couture–cultural trappings that were largely inaccessible to the lower classes. Could the split reaction to tuberculosis–the glamorization of the illness and bleak experience of consumption in impoverished Victorian communities–have more to do with upper-class anxieties about potential class atrophy? Is it reasonable to view upper-class constructions of tuberculosis as a way to maintain class order? That fashion was implemented as a material tool, in part, to frame tuberculosis as an elevated form of suffering, creating a psychological distance from the unsavory realities of lower-class experiences of tuberculosis (pollution, poor hygiene and sanitation, poverty, and crowded urban conditions)?

The book is certainly focused on the upper and middle classes, because that is the part of the story that has not been investigated by those working on the history of tuberculosis. A great deal of the scholarship on the illness is actually centered on the disease in the working classes, the crusades against the illness in the later part of the 19th century as well as the disease’s connections to the Romantic poets. Women, however, are mostly absent from the work on the period from 1780-1850 and only come to the fore in the model of fallen womanhood embodied by the opera heroines of the later 19th century. I felt it was important to put women back into the narrative and to explain how the beautiful dying consumptive of the literary world could co-exist with Engels’ hollow-eyed ghosts. It turns out that in the nineteenth century, consumption was characterized by two distinct and seemingly unrelated discourses, in which victims from the more prosperous classes were lauded while poorer victims were stigmatized. The management of the malady varied with social status and in many respects was treated as a different entity, depending upon the quality and character of its victim. The understanding that tuberculosis was partially linked to social status was crucial in determining the individual’s way of life and, as such, his or her environment. Environment became the predominant explanation for tuberculosis in the working classes. This, in turn fostered a negative perception of the illness in these groups. Instead of victims, members of the lower orders were presented, by social reformers and medical investigators, as the architects of their own demise. In the more prosperous classes, by contrast, consumption was primarily viewed as the consequence of a hereditary defect, one complicated by exciting causes. This more benign presentation of the disease only offered the affluent victim limited control over the circumstances that provoked the illness.

Did tubercular fashions make it as far as the European colonies ?

Traveling to a warmer climate (usually to Southern France or Italy) was often prescribed for those suffering from the illness; however, the explanation of the causes of consumption differed in those areas. As a consequence, the theoretical underpinnings that made the disease fashionable did not hold the same sway. For instance, on the European continent, particularly in the south, consumption was generally regarded as a contagious disease, one spread through the air or through contact with either infected persons or materials. Elsewhere, in England for instance, tuberculosis was viewed as the result of a breakdown in an individual’s constitution, a flaw that was frequently inherited, passed from parents to offspring like physical characteristics such as facial features and hair color. Hereditary rationalization carried weight in situations where the disease carried off entire families and when only some individuals were affected, as it was the consumptive constitution that was passed down and not the illness itself, and it was that constitution that was denoted by beauty in the female.

Your research focuses on the religious dimensions of tuberculosis, particularly popular discourses that presented women consumptives as ‘blessed’ by the physical and spiritual beauty endowed by the disease. Were these views endorsed by clerics? Did religious institutions and ecclesiastics support or contest these claims, or were they treated as secular affairs?

Consumption, as an affliction from which neither class, wealth, nor virtue provided any protection, required rationalization in an effort to make the loss of loved ones more bearable. God’s will would be re-employed by evangelicals and social reformers to fashion meaning and explain cause, by creating a vision of consumption that linked fate, personality and inner truth to clarify both illness and death. Consumptives found comfort and meaning for their suffering in the belief that the disease was part of the Lord’s will. Suffering, illness and death were bound up with notions of providence and provided the opportunity to test the victim’s faith; as such, submission and resignation were the appropriate response. The acquiescence to the inevitability of death marked a transition from a way of living to a way of dying, and an acknowledgment of the presence of consumption often led to a process of self-examination as part of the preparation for death. The importance of submission to the will of God and the Christian idea of death, continued as a significant feature of the approach to the consumptive death well into the nineteenth century.

Tuberculosis seems to have been, in a sense, a ‘privileged’ disease. After all, it was considered fashionable: it influenced literature, fashion, and style; it elevated the infected individual to a plane of respectability and spiritual enlightenment. Why tuberculosis? Why didn’t other diseases, such as cholera, etc., have the same variety of cultural clout?

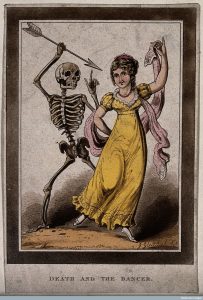

In general, infectious diseases adhere to an epidemic pattern. Initially, they increase very quickly; then, having attained a certain level, slowly fade in intensity and incidence. Despite the fact that the development and course of tuberculosis is less “flashy” than other contagious illnesses, it still follows a typical epidemic cycle of infection, though the progress is often extraordinarily slow, taking decades rather than weeks or months. Consumption’s extended and seemingly invisible period of incubation and vague symptoms, meant the disease became both a way of living as well as a way of dying. Moreover, unlike diseases that disfigure the body suddenly and kill rapidly (like smallpox & cholera), the length of the assault and physical wreckage created by consumption differed. For instance, its symptoms were believed to increase the attractiveness of its victim as its effects became visible in the complexion, eyes, and even the smile. This beauty was denoted by thin frames, long swan-like necks, large dilated eyes accented by luxurious eyelashes, white teeth, and pale complexions accented by blue veins and rosy cheeks.

Having published this monograph, what do you hope readers will take away from Consumptive Chic?

I hope it challenges other scholars to examine those parts of the stories that are missing and to look to interdisciplinary approaches to aid in accessing the various aspects of the disease experience. I was, and remain, interested in the ways in which people bought into the concepts we discuss in medical humanities and it is only by examining the application of these theories that we can hope to understand all the facets of illness. These are also approaches that are applicable to medical practice today, as notions of illness continue to cross the boundaries between medicine and society, just as they did in the eighteenth and in the nineteenth centuries when the association between tuberculosis, society and the sick individual was a fluid relationship whose terms were constantly being re-negotiated, changing and adapting to new social conventions and emerging medical information.

For more about Consumptive Chic, please read the annotation in the LitMed Database.