Early in the morning on October 7th, a Saturday so delightfully sunny and warm that it no doubt belonged to the extended summer of 2017, a contingent of NYU medical students boarded a packed southbound Amtrak train at Pennsylvania Station. Shepherded by second-year students Mackenzie Roof and Nishanth Iyengar, the co-leaders of the medical school’s History of Medicine Club, the enthusiastic group of 15 was headed to Philadelphia to visit the renowned Mütter Museum. The Museum was founded in the midst of the American Civil War to “help the public understand the mysteries and beauty of the human body and to appreciate the history of diagnosis and treatment of disease.” Many of the pathological entities encountered in medical school are understood only in words or through microscopic images, so this trip was an especially exciting and unique opportunity to actually visualize many of these disease processes on a macroscopic scale.

From the new first-year students who had received their white coats just weeks earlier to the seasoned fourth-years who would be granted their medical degrees in the not-too-distant future, everyone in the group relished the hours they spent immersed in the Museum’s extraordinary collections. Below is a collection of their reflections.

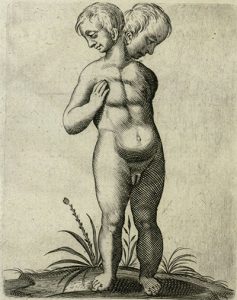

The trip to the Mutter Museum brought me right down memory lane. Though I had visited once before, it was like seeing the museum for the first time now that I’ve begun medical school and was in the company of such knowledgeable 2nd and 4th year students. In particular, one of my favorite exhibits was “Imperfecta.” It was an interesting illustration of how the “monsters” of the past became the teratology of today. As a group, we speculated about the causes of the fetal abnormalities on display. There were many tie-ins to the Core Foundations of Medicine material we were just studying, like the importance of folic acid during pregnancy to prevent neural tube defects. All in all, it was a pleasure to learn more about the history of medicine and I look forward to future events!

Darlina Liu, first-year

Conjoined twins. Source: Fortunio Liceti, De monstrorum caussis, natura, 1634. Courtesy of the Historical Medical Library of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia.

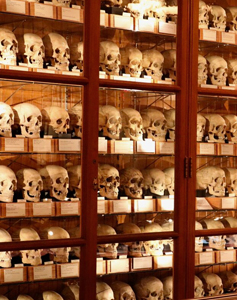

It was a lot smaller than I had imagined, mostly because I was comparing it to the Hunterian Museum in London. But I thought the quality of material there was irreplaceable and thoughtful: I liked how they had themes such as fairytales, the Civil War and “monsters,” that gave context to the information and displays. My favorite parts of the museum however were the art gallery and wall of skulls. What made the skull display so special to me was that the subjects were named, and often showed cause of death or occupation. Overall, I had anticipated a larger museum, but what made the Mutter special was its ability to weave STORIES into its displays; it wasn’t just a collection of items — they were placed in a carefully thought-out context that made the experience actually memorable.

It was a lot smaller than I had imagined, mostly because I was comparing it to the Hunterian Museum in London. But I thought the quality of material there was irreplaceable and thoughtful: I liked how they had themes such as fairytales, the Civil War and “monsters,” that gave context to the information and displays. My favorite parts of the museum however were the art gallery and wall of skulls. What made the skull display so special to me was that the subjects were named, and often showed cause of death or occupation. Overall, I had anticipated a larger museum, but what made the Mutter special was its ability to weave STORIES into its displays; it wasn’t just a collection of items — they were placed in a carefully thought-out context that made the experience actually memorable.

Emily Jang, first-year

The Mütter Museum reminded me a lot of the Hunterian Museum in London, although much more manageable for a day trip. My favorite case was the one on the Brothers Grimm fairytales and their association with medical “monsters.” I found it interesting that a lot of the museum focused on birth defects and how they were viewed by society. Cultures seek to understand and explain the world around them, often through stories. In this case, the deformities might be explained by a god smiting a family or a curse targeting a village because without any other explanation, it can seem truly terrifying that this can happen to anyone. As someone who has always found folklore, mythology, and religion very interesting, I was fascinated to learn more about the fairytales and how they were rooted in these cultural explanations. Additionally, the skull exhibit was awesome because we have just completed our study of head and neck anatomy and are currently in our neurology unit. It was very topical to learn about the different diseases and see how that impacts the skull’s formation. Many of the descriptions under the skulls recorded when and how the person died, which was an interesting anatomical correlate and also humanized the exhibit.

The Mütter Museum reminded me a lot of the Hunterian Museum in London, although much more manageable for a day trip. My favorite case was the one on the Brothers Grimm fairytales and their association with medical “monsters.” I found it interesting that a lot of the museum focused on birth defects and how they were viewed by society. Cultures seek to understand and explain the world around them, often through stories. In this case, the deformities might be explained by a god smiting a family or a curse targeting a village because without any other explanation, it can seem truly terrifying that this can happen to anyone. As someone who has always found folklore, mythology, and religion very interesting, I was fascinated to learn more about the fairytales and how they were rooted in these cultural explanations. Additionally, the skull exhibit was awesome because we have just completed our study of head and neck anatomy and are currently in our neurology unit. It was very topical to learn about the different diseases and see how that impacts the skull’s formation. Many of the descriptions under the skulls recorded when and how the person died, which was an interesting anatomical correlate and also humanized the exhibit.

Mackenzie Roof, second-year

The Mutter Museum was a great experience seeing things that we have learned about in class or have seen our patients have but never saw the pathology. It was particularly memorable because while histology is emphasized in our classes, we rarely have the chance to see the macroscopic pathologies in our patients (ie. large ovarian cyst, familial adenomatous polyposis in the colon, birth defects). Also, due to prevention and modern treatments today, as students in New York City, we rarely see the serious manifestations of diseases such as syphilis, advanced melanoma, and Pott’s disease. It was a sobering reminder of what health was like for people less than a hundred years ago and the importance of prevention and screening and continued investments in our public health infrastructure.

The Mutter Museum was a great experience seeing things that we have learned about in class or have seen our patients have but never saw the pathology. It was particularly memorable because while histology is emphasized in our classes, we rarely have the chance to see the macroscopic pathologies in our patients (ie. large ovarian cyst, familial adenomatous polyposis in the colon, birth defects). Also, due to prevention and modern treatments today, as students in New York City, we rarely see the serious manifestations of diseases such as syphilis, advanced melanoma, and Pott’s disease. It was a sobering reminder of what health was like for people less than a hundred years ago and the importance of prevention and screening and continued investments in our public health infrastructure.

Monica Chan, fourth-year

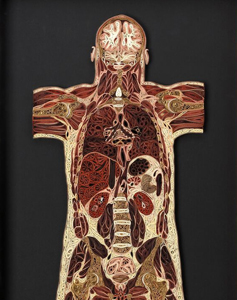

As a devout fan of the Hunterian Museum in London, it was wonderful to see its American incarnation in the Mutter. The history of medicine, with all its surprise turns, quirks, and amusing anecdotes, is something worth studying and learning as a medical student, and there was no better place to do so than at the Mutter. I was particularly impressed by the wall of skulls with their three-sentence, often abrupt stories, as well as the Lisa Nilsson exhibit – a wonderful example of art meeting science. Thank you so much for making the excursion happen!

As a devout fan of the Hunterian Museum in London, it was wonderful to see its American incarnation in the Mutter. The history of medicine, with all its surprise turns, quirks, and amusing anecdotes, is something worth studying and learning as a medical student, and there was no better place to do so than at the Mutter. I was particularly impressed by the wall of skulls with their three-sentence, often abrupt stories, as well as the Lisa Nilsson exhibit – a wonderful example of art meeting science. Thank you so much for making the excursion happen!

Tara Richter Smith, first-year

The Mutter Museum housed a delightful, somewhat eccentric collection of medical “objects.” These included contemporary art, anatomical specimens, historical instruments and medications. I found myself wondering whether the museum (particularly the bottom floor) was more about the history of medical treatment or the history of disease, in particular the history of disfiguring diseases. Is the latter a useful endeavor? On the one hand, I felt guilty for taking voyeuristic pleasure in seeing these “medical oddities. On the other, each display case was filled with interesting glimpses into how the human body (dis)functions, and isn’t that how we learn in medicine?

The Mutter Museum housed a delightful, somewhat eccentric collection of medical “objects.” These included contemporary art, anatomical specimens, historical instruments and medications. I found myself wondering whether the museum (particularly the bottom floor) was more about the history of medical treatment or the history of disease, in particular the history of disfiguring diseases. Is the latter a useful endeavor? On the one hand, I felt guilty for taking voyeuristic pleasure in seeing these “medical oddities. On the other, each display case was filled with interesting glimpses into how the human body (dis)functions, and isn’t that how we learn in medicine?

Gillian Stein, first-year

All images courtesy of the Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia