Listen*:

Transcript:

1

You, student, whistling those elusive bits

of Schubert when phut, phut, phut, throbbed the sky

of London. Listen: the servo-engine cut

and the silence was not the desired silence

between the two movements of music. Then

Finale, the Aldwych echo of crunch

and the urgent ambulances loaded

with the fresh dead. You, young, whistled again,

entered King’s, climbed the stone-murky steps

to the high and brilliant Dissecting Room

where nameless others, naked on the slabs,

reclined in disgraceful silences–twenty

amazing sculptures waiting to be vandalised.

2

You, corpse, I pried into your bloodless meat

without the morbid curiosity of Veslius,

did not care that the great Galen was wrong,

Avicenna mistaken, that they had described

the approximate structure of pigs and monkeys

rather than the human body. With scalpel

I dug deep into your stale formaldehyde

unaware of Pope Boniface’s decree

but, as instructed, violated you–

the reek of you in my eyes, my nostrils,

clothes, in the kisses of my girlfriends.

You, anonymous. Who were you, Mister?

Your thin mouth could not reply, ‘Absent, sir,’

or utter with inquisitionary rage.

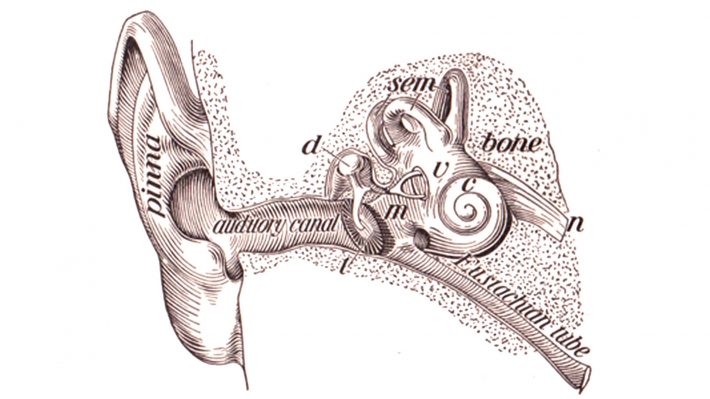

Your neck exposed, muscles, nerves, vessels,

a mere coloured plate in some Anatomy Book;

your right hand, too, dissected, never belonged

it seemed to someone once shockingly alive,

never held surely, another hand in greeting

or tenderness, never clenched a fist in anger,

never took up a pen to sign an authentic name.

You, dead man, Thing, each day, each week,

each month, you slowly decreasing Thing

visibly losing Divine proportions,

you residue, mere trunk of a man’s body,

you, X, legless, armless, headless Thing

that I dissected so casually.

Then went downstairs to drink wartime coffee.

3

When the hospital priest, Father Jerome,

remarked, ‘The Devil made the lower parts

of a man’s body, God the upper,’

I said, ‘Father, it’s the other way round.’

So, the Anatomy Course over, Jerome,

thanatologist, did not invite me

To the Special Service for the Twenty Dead,

did not say to me, ‘Come for the relatives’ sake.’

(Surprise, surprise, that they had relatives

those lifeless-size, innominate creatures.)

Other students accepted, joined in the fake chanting,

organ solemnity, cobwebbed theatre.

And that’s all it would have been,

a ceremony propitious and routine,

an obligation forgotten soon enough

had not the strict priest with premeditated rage

called out the Register of the Twenty Dead –

each non-cephalic carcass gloatingly identified

with a local habitation and a name

till one by one, made culpable, the students cried.

4

I did not learn the name of my intimate,

the twentieth sculpture, the one next to the door.

No matter. Now all these years later

I know those twenty sculptures were but one,

the same one duplicated. You.

I hear not Father Jerome but St. Jerome cry,

‘No, John will be John, Mary will be Mary,’

as if the dead would have ears to hear

the Register on Judgement Day.

Look, on gravestones many names.

There should be one only. Yours.

No, not even one since you have no name.

In the newspapers’ memorial columns

many names. A joke.

On the canvases of masterpieces

the same figure always in disguise. Yours.

Even in the portraits of the old anchorite

fingering a dry skull are you half concealed

lest onlookers should turn away blinded.

In certain music, too, with its sound of loss,

in that Schubert Quintet, for instance,

you are there in the Adagio,

playing the third cello that cannot be heard.

You are there and there and there, nameless,

and here I am older by far and nearer,

perplexed, trying to recall what you looked like

before I dissected your face–you, threat,

molesting presence, and I in a white coat

your enemy, in a purple one, your nuncio,

writing this while a winter twig, not you,

scrapes, scrapes the windowpane.

Soon I shall climb the stairs. Gratefully,

I shall wind up the usual clock at bedtime

s (the steam vanishing from the bathroom mirror)

with my hand, my living hand.

Poet’s Commentary:

“I was a medical student in 1944 at King’s College in London . . . at that time there were bombs coming over, and one of them fell very close to King’s College . . . in fact, it caused more casualties than any of the other bombs. I happened to be in a bus, about to go over to King’s College to do some dissection, and the bus stopped. I got out of the bus, and continued my journey on, and saw the ambulances, and the dead being taken away, and have never written about it until fairly recently. Wordsworth once called poetry ’emotion recollected in tranquillity,’ so perhaps this poem illustrates that definition.”

*Audio and text of commentary and poetry reading reproduced with the permission of Dannie Abse. Copyright (c) Dannie Abse. All rights reserved.

Poem appears in the Abse collection, Be Seated, Thou , to be published by Sheep Meadow Press in January, 2000 (PO Box 1345, Riverdale, NY,10471; tel. 718-548-5547)