Commentary by P. Ravi Shankar, M.D. and Rano Mal Piryani, M.D., Department of Medical Education, KIST Medical College, Lalitpur, Nepal

In previous articles in the Literature, Arts, and Medicine blog we discussed sowing the seeds of Medical Humanities in the Himalayan country of Nepal; teaching Medical Humanities (MH) in English which, though the language of instruction, is not the native language of the participants; and also the challenge of creating and maintaining participant interest in MH.

MH was started as a voluntary module at Manipal College of Medical Sciences (MCOMS), Pokhara (1) and then we (PRS and RMP) conducted modules for faculty members at KIST Medical College (KISTMC), Lalitpur. In 2009 and 2010 we conducted modules for first year students at KISTMC. In this blog article we describe what in our opinion worked in the four modules and what did not and reflect on possible reasons for the same. Our experiences may be of interest to other MH educators, especially in developing countries.

What Worked

Small groups:

Small groups worked well in all four modules we organized and are an excellent way to learn MH. Small groups work together at a given activity and share ideas. In MH, unlike other more formal medical subjects, there may be no particular well defined solution of a problem. Participants mainly reflect on a painting, a case scenario, or a problem and share their views. In social sciences as opposed to the biological and physical sciences there may not always be a ‘particular’ way to solve a problem. One problem we faced was that not all members of small groups were active. We could only gently nudge the reluctant individuals into more active participation. We tried giving participants greater responsibility for self-managing small groups. We asked the groups to select from among themselves a group leader, a time keeper, a recorder and a presenter and rotate these roles during different sessions.

Paintings:

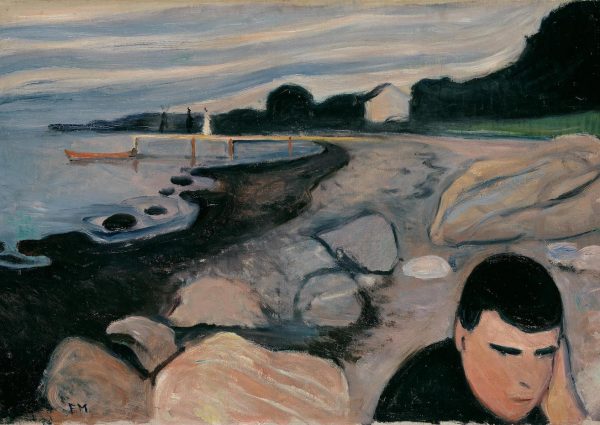

Paintings were a great success. We incorporated them more and more in successive modules. We have described our experience of using paintings in MH in a recent article. (2) Our major source of paintings was the Literature, Arts, and Medicine Database maintained by New York University. The database arranges literature excerpts, paintings, and videos according to different subject categories. Online access to photos of paintings and their annotations were useful. Participants were able to relate to the paintings, which were mainly from a western context. In Nepal only students from a science background take up medicine and most were not previously exposed to art appreciation and critical analysis of paintings. Most participants enjoyed the paintings but also recommended more use of art from Nepal.

Case scenarios and role-plays:

These were extensively used throughout. The case scenario usually had an ethical or a social issue which had to be explored wit role-plays by participants. A variety of issues such as diseases with social stigma, abortion, euthanasia, mental illness, patient confidentiality–among others–were explored. Student participants enjoyed role-play and interpreting different scenarios. Students brought out many issues and sometimes interpreted the scenario in a novel manner. Role-plays in KISTMC also served to bridge to a certain extent the language barrier as they were conducted in Nepali, the national language. We also introduced an exercise of interpreting scenarios depicted in paintings using role-plays, which was extremely popular with students. Interestingly, participants of the faculty module had problems with certain role-plays dealing with sexual and reproductive issues.

Debates:

Debates were used to explore certain issues in MH, for example, euthanasia, whether students from non-science backgrounds should be allowed to take up medicine, the nature of the doctor-patient relationship. Participants enjoyed debates but due to time constraints, full fledged debates–which require more thought and deliberation–could not easily be organized. Debates were more effective in the recently concluded MH module (2010). Students showed greater interest in the module as evidenced by their greater participation in group activities and high attendance (above 80%) even before assessments. In light of our previous experience, we modified the format so that the group/s speaking for the proposition would first put forward their points and then the group/s speaking against would counter those points. In addition to arguments prepared during the ten minutes allotted to the activity, students also had to oppose arguments put forward by the opposing group/s on the spot. We concluded that debates can be a good way to explore controversial issues.

Flip charts and flip boards:

These have the advantages of flexibility and ease of use. Flip charts are an excellent way for noting down the results of small group work and for small groups to present their findings to the whole house. We have been using flip charts effectively during Pharmacology practical sessions. During MH sessions flip charts were used to note main points and by presenters to guide their presentations. Flip charts are an excellent way for noting down the results of small group work and for small groups to present their finding to the whole house. On reflecting after the sessions it was our opinion that participants used flip charts in the same manner during both MH and Pharmacology practical sessions. Flip charts could have been used in a more creative manner during MH sessions. Certain groups did so but we could have developed and given guidelines to the groups. Creativity also may require a certain amount of artistic talent and ability among group members.

Venue of the sessions:

All student sessions were conducted in the college auditorium. The auditorium offers an empty space about 30 m x 30 m which can be arranged and organized to meet specific requirements. Students could be arranged in small groups with a separate area for role-plays and a main projection area. The only problem was the auditorium was being used for a variety of activities and we had to rearrange it before each session. A free area that can be reconfigured and rearranged to meet specific requirements is ideal for small group sessions that require creativity and flexibility, unless you can get a dedicated area for sessions, which can be difficult in developing nations.

What Did Not Work

Literature excerpts:

Literature excerpts have been widely used in MH sessions in the west. In the module at MCOMS, Pokhara, and in the faculty module at KISTMC we used literature excerpts. The excerpts were in English and participants often felt they were difficult to understand and the language was difficult. In MCOMS the participants were multinational. In KISTMC the major problem was getting literature excerpts in Nepali relevant to MH and the particular topic being covered. For English excerpts the Literature, Arts, and Medicine Database made the task easier as excerpts were arranged according to subject matter. We did not use literature during the two student modules; however, considering the complexity of issues which can be provoked and addressed by good literature we are thinking about how to incorporate it in future modules.

Reflective writing assignments:

MH is basically a process of reflection about various events in medicine. Reflective writing can be a good method to get participants to reflect. We tried giving reflective writing assignments to participants, but only participants in the MCOMS module, which was voluntary, were regular in submitting their assignments. Assignments were not used in the faculty module. In the 2009 student module submission was irregular. In the 2010 module students submitted more regularly. In South Asia compared to the west students are younger and less mature when they enter medical school. There is a dichotomy between arts and science in the education system. Creative writing and keeping a personal diary are not very common. These could be reasons why students were not very comfortable with reflective writing. However the interest and participation of the 2010 batch gives us hope that this could be a modality to be considered in future.

Medical Humanities online:

We created a medical Humanities group on the web (a private Google group). Slides of various topics, other material and selected publications related to MH were uploaded. There is also a discussion forum where individuals can discuss and comment on various topics. Participation in the group is voluntary. We invited selected faculty and other experts and sent an invitation to all students who participated in the module. Problems of net access, lack of time, and a hectic academic schedule were cited as possible reasons for not joining and not being active in the group.

Creating interest among other faculties:

Over the four years of MH only few faculty members were interested in being module facilitators. During the 2009 student MH module six faculty members from various departments joined as co-facilitators. Many of them were not entirely comfortable with small group learning and with using art and role-plays in medical education. Many were clinicians and their tight clinical schedule could have been a hindering factor. During informal discussion with western MH educators a factor which emerged was only faculty with a personal interest in the arts or with a hobby related to the arts like photography, painting, sculpture and creative writing may be interested in MH. Lack of success in creating new facilitators may be a limiting factor for the module in future.

Creating linkages with persons outside the traditional world of medicine:

In the west MH programs use resources and facilities from many sources. Artists, writers, philosophers and others have made a significant contribution to MH. In the west most medical schools are in a University sharing a campus with other disciplines while in Nepal medical schools usually exist in isolation. We were successful to a certain extent in that we wrote about using art in the education of doctors for a Nepalese magazine and created a certain amount of interest among people outside traditional medicine. The challenge will now be to transform interest into action.

The situation in South Asia is in many ways different from the west. Also batches of students and individuals vary in their interests and aptitude. Tailoring a module to meet the aspirations of groups and individuals is a challenge. Flexibility and an open mind could be important in meeting the challenge!

References

1.Shankar, P. R. A voluntary Medical Humanities module at the Manipal College of Medical Sciences, Pokhara, Nepal. Family Medicine 2008; 40: 468-70.

2.Shankar, P. R. and Piryani R. M. Using paintings to explore the Medical Humanities in a Nepalese medical school. BMJ Medical Humanities 2009; 35:121-122.