Dr P. Ravi Shankar has been facilitating medical humanities sessions for over eight years, first in Nepal and currently in Aruba in the Dutch Caribbean. He has a keen interest in and has written extensively on the subject. He has previously written several pieces for the Literature, Arts, and Medicine blog.

I have always enjoyed facilitating medical humanities sessions right from the time I facilitated my first voluntary module for interested students at the Manipal College of Medical Sciences, Pokhara, Nepal in 2007. The energy level during the inaugural module was incredible. The participants, both students and faculty, and I really enjoyed the evening sessions and the feeling of freedom and discovery as we did various activities and discussed different issues. We had a lot of fun.

When I joined Xavier University School of Medicine (XUSOM), on the beautiful island of Aruba in January 2013, the Dean, Dr Dubey was keen that I facilitate a medical humanities module for the undergraduate medical (MD) students. The school had just shifted to an integrated, organ system-based curriculum from the traditional discipline based model common in offshore Caribbean medical schools. Didactic lectures were the main teaching-learning methodology but the school was working towards introducing small group activities and problem based learning sessions. I decided to facilitate a short medical humanities (MH) module for the incoming first semester students.

At that time the school had only lecture rooms and a traditional desk and chair seating arrangement. Luckily the desks could be rearranged, and I conducted my first session in the lecture hall with the students arranged in four small groups. Some of the students had completed a premedical course of study in the institution and were only familiar with lecture based-teaching. Small group activity was something new for them. Medical humanities do not occupy an important position in the United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) Step 1, and students in Caribbean medical schools focus on step 1 preparations. Subjects which are not tested or tested less in step 1 are not considered important. MH is thus not commonly offered in offshore schools.

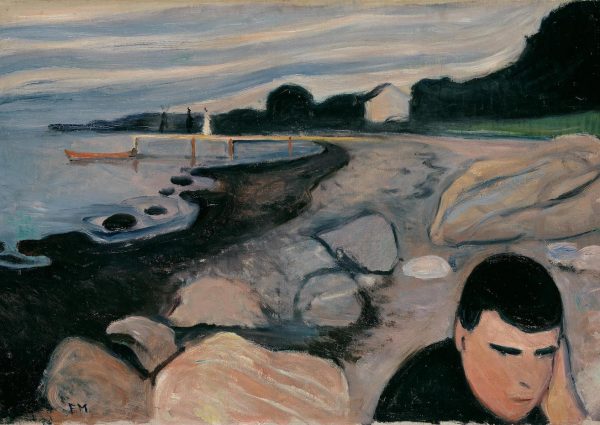

The first group of students: I concentrated on six topics for the inaugural and subsequent medical humanities modules. These were empathy, the patient, the family, the doctor, the patient-doctor relationship, and the medical student. The modules were activity based and I used case scenarios, role-plays, debates and paintings to explore different subjects. The learning objectives of each session were listed in the study outline posted on the class server and also highlighted at the beginning of the sessions. For example, for the session ‘The doctor’ had these objectives:

At the end of this session students will be able to:

• Obtain a perspective on what it means to be a doctor

• Explore balancing a meaningful personal life with a busy and rewarding professional career

• Understand ‘certain’ influences and pressures on a doctor today

• Interpret the changing role of doctors through paintings and stories

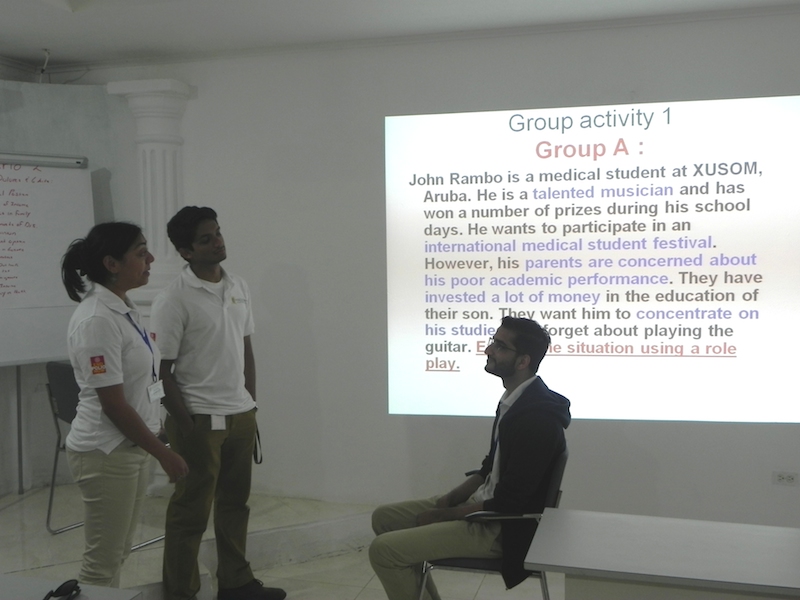

Certain students enjoyed the freedom and flexibility offered by the module while others tended to ‘misuse’ the freedom. I had a few disciplinary issues which I had to deal with carefully as I did not want students to feel intimidated. I did not confront the students with disciplinary problems during the class but had a quiet word with some of them after the session. The formative assessment rubric addressed issues like attendance, punctuality, discipline and commitment and students who worked harder and showed greater commitment performed better in the assessment. Also for each session each small group had a group leader who was responsible for keeping the group active and focused on various tasks. The role was rotated during different sessions. I wanted them active, focused and interested in the activities and the subject. Among the various activities employed, students eventually did well in interpreting paintings and in the debates. The role-plays however needed more work. They often did not explore the issues in sufficient depth and students felt inhibited to act out certain scenarios in front of their classmates. This was in contrast to the students in Nepal who had enjoyed the role-plays with their skits and acting became richer and more complex as the module progressed.

Two of the role-plays I introduced were:

1. Ms. Mohini is a 28 year old lady from South Asia who was trafficked and was compelled to become a commercial sex worker. After ten years of service she was sent back to her country and village as she became HIV positive. The disease is at an advanced stage and she has no money for treatment. Her family has reluctantly allowed her to stay with them but is not happy that a retired prostitute is living with them. Explore what it means to be sick using a role-play. (Used during the session ’What it means to be sick’)

2. Dr. Richard is an Internal medicine specialist in Toronto. He has been treating a twenty-two year old college student named Rachel for the last five years. The lady suffers from severe attacks of migraine and is on drug prophylaxis. Richard has realized that he is in love with Rachel. He wants to live happily ever after with her. However, he is not sure about whether it would be correct for a doctor to marry his young female patient. Analyze the issues involved using a role-play. (Used during the session ‘The patient-doctor relationship’)

Among the different cohorts of first semester students I found the fall 2013 and the spring 2014 cohorts to be the most interested and active (XUSOM, like most offshore Caribbean medical schools, admits students three times a year in January, May and September). These students created interesting role-plays to explore various issues based on the scenarios provided. The debates and the interpretation of paintings were also rich and varied. I enjoyed facilitating these groups. These two cohorts had a few students who were active, dynamic and committed and with good leadership skills. They were able to motivate and stimulate their colleagues to give their best. They also had good acting skills, which was useful during the role-plays. With greater exposure to small group learning these cohorts were more comfortable with group work and the academically stronger students were more willing to support students who were less strong academically. Class sizes at XUSOM are small and till date around 90 students have completed the program.

Co-facilitators:

At XUSOM many students, though American or Canadian citizens, are of South Asian or Middle Eastern descent. There were no major cultural and other problems involved for me in facilitating this group of students. Many students were interested in this new perspective and in understanding the art of medicine. XUSOM also offers courses in English and scientific communication to premedical students and the faculty members teaching this subject eventually joined me as co facilitators during the module. They were from a liberal arts background and were able to offer a ‘different’ (often a layperson) perspective during the various activities and the discussion. A challenge I faced similar to Nepal was that not many ‘medical school faculty’ were interested in MH and in co-facilitating the module, though two or three did attend certain sessions.

Small group learning room and other developments:

Over the preceding twenty-month period MH has become an accepted part of the school curriculum. The school created a separate room dedicated to small group learning with comfortable seating, white boards, flip charts and projection facilities. The room is now being used for various small group activities including problem based-learning. Slowly there is a greater number of small group learning and self-directed learning activities at the school. MH is now an established discipline at the school and the module is a part of the patient, doctor and society module for first semester students. Students’ ability to show empathy, make their patient feel comfortable and obtain a proper history is assessed at the end of the first semester using standardized patients. Students also visit a local general practitioner every fortnight to learn history taking skills and interact with patients. I am sure MH will progress and grow in the sunny, hospitable climate of the one happy island of Aruba in the Southern Caribbean.

You can learn more about the MH modules in a forthcoming article in the Asian Journal of Medical Sciences titled ‘Four semesters of medical humanities at the Xavier University School of Medicine, Aruba.’ (in press)

Photos courtesy of Dr. P. Ravi Shankar