As one might expect, much of medical training occurs in the inpatient setting. Teaching hospitals, brimming with an elaborate hierarchy of trainees and supervisors, offer a critical mass of patients and pathology. Typically these patients present with exceptionally complex histories and comorbidities enriching the substrate of the teaching environment. Counter-intuitively, most doctors do not work in inpatient settings. This is especially true for psychiatry wherein the great majority of practitioners work in the outpatient setting, practicing various forms of psychotherapy.

Unlike in other fields of medicine, residents in psychiatry experience virtually no outpatient psychiatry until their third year (PGY-3). Most psychiatry residents therefore spend a minimum of six years of training before they venture beyond the frontier of outpatient psychiatry, into a wilderness they will eventually call home. For many, this is the moment they have been waiting for since deciding to become a doctor: their first therapy session.

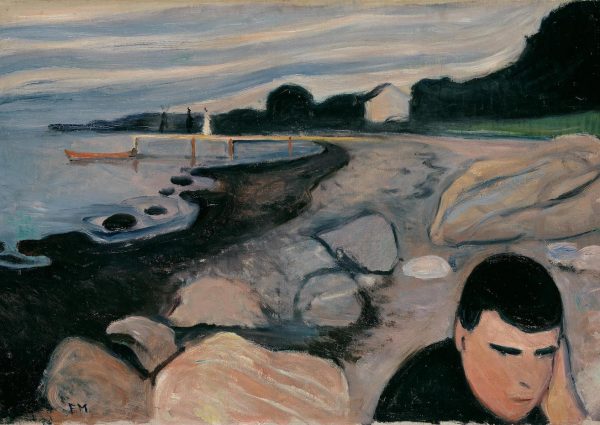

Angst is perhaps the most suitable name for the escalating feeling leading to that first 45-minute office visit. Beyond simple anxiety or worry, there are existential elements implicating one’s life, career, and purpose in the world. Additionally, there is both hope and dread- hope that salvation will eventually come (the patient will get better), and dread that you will be unable to bring it. Unlike the inpatient setting, befit with teams of providers embedded in elaborate systems of care (however under-funded and uncoordinated), the outpatient office can be a shockingly lonely venue, a small island where you sit naked waiting to be eaten by a large animal.

From one perspective, there is not much difference between a typical 20-30 minute encounter or “therapy session” on an inpatient unit and a 45-minute office based session. Yet there is an irrational pressure put upon oneself to make the most of an outpatient visit and a simultaneous intense fear that 45 minutes will be way too long (never in the hospital does one have time to worry about running out of things to say). Undoubtedly connected to the well-intentioned (and yet grandiose) identity as healer, this pressure suggests you alone will be in charge of saving your patient’s life. Adding to this self-conscious uncertainty is the loss of anonymity afforded to inpatient providers. No longer able to hide behind the tribal masks and dress of the hospital ward treatment team, one’s nakedness is more viewable in the outpatient setting.

Most concerning is the realization that, unlike inpatients who often draw from a more familiar cast of acutely ill characters (the demented elderly woman who screams all night after a recent infection, the manic psychotic young man from another state off his meds, the chronically homeless schizophrenic with a recent decompensation…), outpatients can come from anywhere. Fresh off the inpatient unit, I remember once thinking in early July, “Who is this stranger?” I was sitting opposed to a fashionably-dressed middle-aged man on a single antidepressant discussing his upcoming trips for business and summer vacations. Several years since a recent major depressive episode and suicide attempt, it was as though we sat chatting, comfortable by a campfire, the specter of his disease far from our minds.

It wasn’t until I returned to the hospital that I appreciated the outpatient setting for what it truly is. Amidst the reverse culture shock of a long call night in the emergency room, I found myself between three newly admitted and screaming patients; one in withdrawal begging for more benzos, another acutely manic and irritable, the third demanding discharge despite a near-lethal overdose just hours afore. I missed my verdant, tranquil island.

It was at this point that I could look back at the thick, threatening, overgrown paths I had traversed and appreciate the open air of my surroundings. It was a few weeks later until I realized who else had been through those woods, lived even deeper in the dark recesses of the forest.

Now sitting in my office I strategize with patients on how to maximize their island time. I wonder how to keep the campfire burning so that we may “talk” as long as possible. And most importantly I try to mentally prepare for the day when a patient must return to those deep dark woods and how I can best make that journey with them.

-Arthur Robinson Williams

Arthur Robinson Williams is a PGY-3 Resident in the Department of Psychiatry at New York University specializing in addiction psychiatry, ethics, and research. He earned his M.D. and a Master in Bioethics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and the Penn Center for Bioethics.

As one might expect, much of medical training occurs in the inpatient setting. Teaching hospitals, brimming with an elaborate hierarchy of trainees and supervisors, offer a critical mass of patients and pathology. Typically these patients present with exceptionally complex histories and comorbidities enriching the substrate of the teaching environment. Counter-intuitively, most doctors do not work in inpatient settings. This is especially true for psychiatry wherein the great majority of practitioners work in the outpatient setting, practicing various forms of psychotherapy.

Unlike in other fields of medicine, residents in psychiatry experience virtually no outpatient psychiatry until their third year (PGY-3). Most psychiatry residents therefore spend a minimum of six years of training before they venture beyond the frontier of outpatient psychiatry, into a wilderness they will eventually call home. For many, this is the moment they have been waiting for since deciding to become a doctor: their first therapy session.

Angst is perhaps the most suitable name for the escalating feeling leading to that first 45-minute office visit. Beyond simple anxiety or worry, there are existential elements implicating one’s life, career, and purpose in the world. Additionally, there is both hope and dread- hope that salvation will eventually come (the patient will get better), and dread that you will be unable to bring it. Unlike the inpatient setting, befit with teams of providers embedded in elaborate systems of care (however under-funded and uncoordinated), the outpatient office can be a shockingly lonely venue, a small island where you sit naked waiting to be eaten by a large animal.

From one perspective, there is not much difference between a typical 20-30 minute encounter or “therapy session” on an inpatient unit and a 45-minute office based session. Yet there is an irrational pressure put upon oneself to make the most of an outpatient visit and a simultaneous intense fear that 45 minutes will be way too long (never in the hospital does one have time to worry about running out of things to say). Undoubtedly connected to the well-intentioned (and yet grandiose) identity as healer, this pressure suggests you alone will be in charge of saving your patient’s life. Adding to this self-conscious uncertainty is the loss of anonymity afforded to inpatient providers. No longer able to hide behind the tribal masks and dress of the hospital ward treatment team, one’s nakedness is more viewable in the outpatient setting.

Most concerning is the realization that, unlike inpatients who often draw from a more familiar cast of acutely ill characters (the demented elderly woman who screams all night after a recent infection, the manic psychotic young man from another state off his meds, the chronically homeless schizophrenic with a recent decompensation…), outpatients can come from anywhere. Fresh off the inpatient unit, I remember once thinking in early July, “Who is this stranger?” I was sitting opposed to a fashionably-dressed middle-aged man on a single antidepressant discussing his upcoming trips for business and summer vacations. Several years since a recent major depressive episode and suicide attempt, it was as though we sat chatting, comfortable by a campfire, the specter of his disease far from our minds.

It wasn’t until I returned to the hospital that I appreciated the outpatient setting for what it truly is. Amidst the reverse culture shock of a long call night in the emergency room, I found myself between three newly admitted and screaming patients; one in withdrawal begging for more benzos, another acutely manic and irritable, the third demanding discharge despite a near-lethal overdose just hours afore. I missed my verdant, tranquil island.

It was at this point that I could look back at the thick, threatening, overgrown paths I had traversed and appreciate the open air of my surroundings. It was a few weeks later until I realized who else had been through those woods, lived even deeper in the dark recesses of the forest.

Now sitting in my office I strategize with patients on how to maximize their island time. I wonder how to keep the campfire burning so that we may “talk” as long as possible. And most importantly I try to mentally prepare for the day when a patient must return to those deep dark woods and how I can best make that journey with them.

-Arthur Robinson Williams

Arthur Robinson Williams is a PGY-3 Resident in the Department of Psychiatry at New York University specializing in addiction psychiatry, ethics, and research. He earned his M.D. and a Master in Bioethics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and the Penn Center for Bioethics. Island Time

As one might expect, much of medical training occurs in the inpatient setting. Teaching hospitals, brimming with an elaborate hierarchy of trainees and supervisors, offer a critical mass of patients and pathology. Typically these patients present with exceptionally complex histories and comorbidities enriching the substrate of the teaching environment. Counter-intuitively, most doctors do not work in inpatient settings. This is especially true for psychiatry wherein the great majority of practitioners work in the outpatient setting, practicing various forms of psychotherapy.

Unlike in other fields of medicine, residents in psychiatry experience virtually no outpatient psychiatry until their third year (PGY-3). Most psychiatry residents therefore spend a minimum of six years of training before they venture beyond the frontier of outpatient psychiatry, into a wilderness they will eventually call home. For many, this is the moment they have been waiting for since deciding to become a doctor: their first therapy session.

Angst is perhaps the most suitable name for the escalating feeling leading to that first 45-minute office visit. Beyond simple anxiety or worry, there are existential elements implicating one’s life, career, and purpose in the world. Additionally, there is both hope and dread- hope that salvation will eventually come (the patient will get better), and dread that you will be unable to bring it. Unlike the inpatient setting, befit with teams of providers embedded in elaborate systems of care (however under-funded and uncoordinated), the outpatient office can be a shockingly lonely venue, a small island where you sit naked waiting to be eaten by a large animal.

From one perspective, there is not much difference between a typical 20-30 minute encounter or “therapy session” on an inpatient unit and a 45-minute office based session. Yet there is an irrational pressure put upon oneself to make the most of an outpatient visit and a simultaneous intense fear that 45 minutes will be way too long (never in the hospital does one have time to worry about running out of things to say). Undoubtedly connected to the well-intentioned (and yet grandiose) identity as healer, this pressure suggests you alone will be in charge of saving your patient’s life. Adding to this self-conscious uncertainty is the loss of anonymity afforded to inpatient providers. No longer able to hide behind the tribal masks and dress of the hospital ward treatment team, one’s nakedness is more viewable in the outpatient setting.

Most concerning is the realization that, unlike inpatients who often draw from a more familiar cast of acutely ill characters (the demented elderly woman who screams all night after a recent infection, the manic psychotic young man from another state off his meds, the chronically homeless schizophrenic with a recent decompensation…), outpatients can come from anywhere. Fresh off the inpatient unit, I remember once thinking in early July, “Who is this stranger?” I was sitting opposed to a fashionably-dressed middle-aged man on a single antidepressant discussing his upcoming trips for business and summer vacations. Several years since a recent major depressive episode and suicide attempt, it was as though we sat chatting, comfortable by a campfire, the specter of his disease far from our minds.

It wasn’t until I returned to the hospital that I appreciated the outpatient setting for what it truly is. Amidst the reverse culture shock of a long call night in the emergency room, I found myself between three newly admitted and screaming patients; one in withdrawal begging for more benzos, another acutely manic and irritable, the third demanding discharge despite a near-lethal overdose just hours afore. I missed my verdant, tranquil island.

It was at this point that I could look back at the thick, threatening, overgrown paths I had traversed and appreciate the open air of my surroundings. It was a few weeks later until I realized who else had been through those woods, lived even deeper in the dark recesses of the forest.

Now sitting in my office I strategize with patients on how to maximize their island time. I wonder how to keep the campfire burning so that we may “talk” as long as possible. And most importantly I try to mentally prepare for the day when a patient must return to those deep dark woods and how I can best make that journey with them.

-Arthur Robinson Williams

Arthur Robinson Williams is a PGY-3 Resident in the Department of Psychiatry at New York University specializing in addiction psychiatry, ethics, and research. He earned his M.D. and a Master in Bioethics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and the Penn Center for Bioethics.

As one might expect, much of medical training occurs in the inpatient setting. Teaching hospitals, brimming with an elaborate hierarchy of trainees and supervisors, offer a critical mass of patients and pathology. Typically these patients present with exceptionally complex histories and comorbidities enriching the substrate of the teaching environment. Counter-intuitively, most doctors do not work in inpatient settings. This is especially true for psychiatry wherein the great majority of practitioners work in the outpatient setting, practicing various forms of psychotherapy.

Unlike in other fields of medicine, residents in psychiatry experience virtually no outpatient psychiatry until their third year (PGY-3). Most psychiatry residents therefore spend a minimum of six years of training before they venture beyond the frontier of outpatient psychiatry, into a wilderness they will eventually call home. For many, this is the moment they have been waiting for since deciding to become a doctor: their first therapy session.

Angst is perhaps the most suitable name for the escalating feeling leading to that first 45-minute office visit. Beyond simple anxiety or worry, there are existential elements implicating one’s life, career, and purpose in the world. Additionally, there is both hope and dread- hope that salvation will eventually come (the patient will get better), and dread that you will be unable to bring it. Unlike the inpatient setting, befit with teams of providers embedded in elaborate systems of care (however under-funded and uncoordinated), the outpatient office can be a shockingly lonely venue, a small island where you sit naked waiting to be eaten by a large animal.

From one perspective, there is not much difference between a typical 20-30 minute encounter or “therapy session” on an inpatient unit and a 45-minute office based session. Yet there is an irrational pressure put upon oneself to make the most of an outpatient visit and a simultaneous intense fear that 45 minutes will be way too long (never in the hospital does one have time to worry about running out of things to say). Undoubtedly connected to the well-intentioned (and yet grandiose) identity as healer, this pressure suggests you alone will be in charge of saving your patient’s life. Adding to this self-conscious uncertainty is the loss of anonymity afforded to inpatient providers. No longer able to hide behind the tribal masks and dress of the hospital ward treatment team, one’s nakedness is more viewable in the outpatient setting.

Most concerning is the realization that, unlike inpatients who often draw from a more familiar cast of acutely ill characters (the demented elderly woman who screams all night after a recent infection, the manic psychotic young man from another state off his meds, the chronically homeless schizophrenic with a recent decompensation…), outpatients can come from anywhere. Fresh off the inpatient unit, I remember once thinking in early July, “Who is this stranger?” I was sitting opposed to a fashionably-dressed middle-aged man on a single antidepressant discussing his upcoming trips for business and summer vacations. Several years since a recent major depressive episode and suicide attempt, it was as though we sat chatting, comfortable by a campfire, the specter of his disease far from our minds.

It wasn’t until I returned to the hospital that I appreciated the outpatient setting for what it truly is. Amidst the reverse culture shock of a long call night in the emergency room, I found myself between three newly admitted and screaming patients; one in withdrawal begging for more benzos, another acutely manic and irritable, the third demanding discharge despite a near-lethal overdose just hours afore. I missed my verdant, tranquil island.

It was at this point that I could look back at the thick, threatening, overgrown paths I had traversed and appreciate the open air of my surroundings. It was a few weeks later until I realized who else had been through those woods, lived even deeper in the dark recesses of the forest.

Now sitting in my office I strategize with patients on how to maximize their island time. I wonder how to keep the campfire burning so that we may “talk” as long as possible. And most importantly I try to mentally prepare for the day when a patient must return to those deep dark woods and how I can best make that journey with them.

-Arthur Robinson Williams

Arthur Robinson Williams is a PGY-3 Resident in the Department of Psychiatry at New York University specializing in addiction psychiatry, ethics, and research. He earned his M.D. and a Master in Bioethics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania and the Penn Center for Bioethics.