Commentary by Bert Hansen, Ph.D., Professor of History, Baruch College, The City University of New York. Author of Picturing Medical Progress from Pasteur to Polio: A History of Mass Media Images and Popular Attitudes in America (Rutgers University Press, 2009).

In people’s minds, July 6 rings no bells. It lights no anniversary fireworks. Yet we all live in a world of new discoveries, headlines proclaiming new cures, and the persistent expectation that new advances will keep coming. Those key features of the modern world were born on July 6, 1885, in a revolutionary shift in ordinary people’s expectations. An old-style medicine that honored white-haired doctors and traditional practice at the bedside was quickly replaced with one characterized by novelties born in laboratories.

The atomic age is readily dated to August 6, 1945, when the bomb exploded over Hiroshima. Biology celebrates November 24, 1859, the publication date for Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species. Molecular biology celebrates 1953 for the journal article in which James Watson and Francis Crick proposed their double helix model for the structure of DNA molecules. In 1955, headlines blared “Victory over Polio: Salk’s Vaccine Works.” Yet Salk’s shots were not the start of laypeople’s enthusiasm for medical advance, they stood in a tradition that began with another kind of injection in the late nineteenth century.

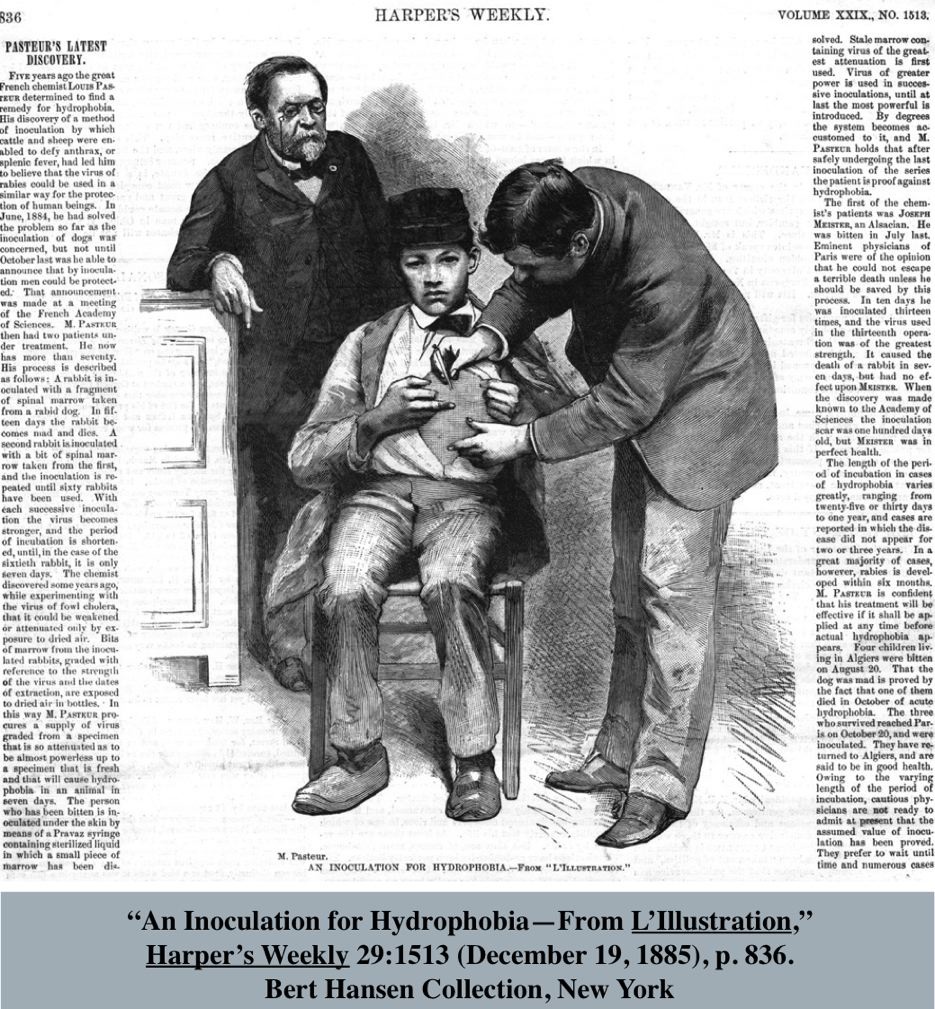

The medical revolution began very quietly in Paris on July 6, 1885, with the first human test of shots to prevent rabies — a relatively uncommon, but widely feared and absolutely fatal disease. Nine-year-old Joseph Meister, mauled on July 4 by a rabid dog, received the first of thirteen injections with a vaccine not yet tested in humans. Louis Pasteur, who developed the remedy, was nervous, and none but his most trusted laboratory associates were present. For about three months there was no publicity.

But within six months — largely caused by events in the United States — headlines around the globe carried news of a medical triumph such as the world had never seen. Children threatened with a horrible death from rabies were saved by these new injections. For the miracle cure, thousands of people bitten by dogs and wolves flocked to Paris from the Americas, eastern Europe, north Africa, even Siberia.

Media coverage in the United States played a unique role in creating a popular enthusiasm for the cure and a new idea of medical progress, both here and aboard. New tools of journalism were at hand: banner headlines, the reporter’s interview, the human-interest story. Cut-throat competition among the penny papers produced an incessant drive to collar readers with exciting stories and to grab them again the next day with new developments.

Story-hungry papers were ready to pounce in December, when little children in the streets of Newark were bitten by a mad dog and a local doctor’s letter to the editor suggested they be rushed to Paris for the new cure — with donations from the public if their parents could not afford it. Within hours factory employees were collecting loose change and delivering it to the doctor’s office. Within two days, papers as far distant as Chicago and St. Louis reported the bites, the donations, and a trip to Paris in the offing for four working-class boys. The story was an editor’s dream: innocent children threatened by an agonizing death, public charity, the problem of stray dogs, doctors and scientists to be interviewed, and a voyeuristic story of the boys’ transatlantic voyage

Artists produced sketches of the boys, the dogs, the local doctors, M. Pasteur, and the steamship. Papers added editorials on science and long articles about Pasteur’s earlier discoveries. The over-the-top coverage was quickly parodied with color cartoons in the weekly humor magazines, Puck and Judge. Much of the news coverage was silly and might have been ephemeral but for the fact that there emerged within it one entirely unprecedented image — the heroic scientist creating medical advances through laboratory research. The public became religiously devoted to this figure.

A rabid dog in Newark produced something no publicist could have achieved. And while the media bonanza was most striking in the United States, medical advance gained similar attention in other countries through the new rabies shots being given in Paris. Within three years, world-wide donations from schoolchildren and from princes built the Pasteur Institute in Paris, followed soon by a score of daughter institutes around the world.

Last year when two Pasteur Institute scientists received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for their identification of the virus responsible for AIDS, the world applauded them for a major breakthrough of modern medicine, a discovery that depended on a tradition just a little more than a century old, the powerful institutionalized process of research and development.

It all started when a boy was injected with weakened virus to save his life. He lived, he thrived, and he became a media celebrity.

In appreciation for rabies shots — but even more for the role of the press in creating the new idea of medical progress, let us all celebrate July 6.