An Interview with Emily Milam, MS4, NYU School of Medicine, Rudin Fellow 2014-15

By: Katie Grogan, DMH, Associate Director, Master Scholars Program in Humanistic Medicine, NYU School of Medicine

The Rudin Fellowship in Medical Ethics and Humanities supports medical trainees at NYU School of Medicine – including medical students, residents, and clinical fellows – pursuing year-long research projects in medical humanities and medical ethics under the mentorship of senior faculty. It was established in 2014 through a grant from the Louis and Rachel Rudin Foundation, Inc and is a core component of the Master Scholars Program in Humanistic Medicine.

Emily receiving her fellowship certificate from Drs. David Oshinsky, her Rudin Mentor, and Lynn Buckvar-Keltz, Associate Dean for Student Affairs, at the Rudin Fellowship Project Showcase, July 7, 2015

How did you become interested in medical photography and why did you decide to develop this into a research project as part of the Rudin Fellowship?

My interest in medical photography stems from a longstanding appreciation of portrait photography, since the two overlap so much. I first took a portrait photography class in college. In medicine, much of our education relies on illustrations from photographs. So when we aren’t learning from the patients themselves in clinical rotations, we’re learning from textbooks and the Internet where we see photos of patients with these diseases. I’ve always wondered what the experience was like for the patient who is photographed. What were they feeling? What did they think would become of that photograph? Did they know it would be in textbooks for thousands of people to see years later? I imagine that the experience would be perhaps embarrassing for some but fulfilling for others. I wanted to explore the different emotions and scenarios in which portrait photographs were taken in medicine.

One component of the project was a historical survey of medical photography. I imagine that most people, whether they are in healthcare or not, know very little about the origins of medical photography. When and how did it become integrated in medical practice?

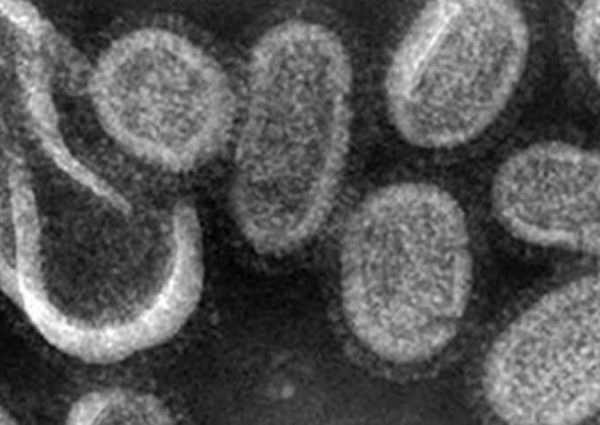

Photography in some form has been around for centuries, starting with principles of the camera obscura. But the birth of photography is often credited to Louis Daguerre, who developed the daguerreotype process – the first photographic image with permanence – in the 1830s. After that it’s thought that the first application of photography to medicine was in the 1840s, when a physician named Alfred Donné published a cytology atlas of 86 daguerreotypes of micrographic images in his book Cours de Microscopie with the help of a photographer named Leon Foucault. The earliest medical portrait is an 1847 photograph depicting a woman with a sizeable goiter, taken by two Scottish photographers, David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson. There are many other examples of medical portraiture in the years thereafter, including the earliest known dermatologic daguerreotype of a burn victim’s distorted face and neck published by a surgeon in Philadelphia’s Medical Examiner. There was also a psychiatrist, Dr. Hugh Welch Diamond, who gathered a collection of psychiatric portraits of asylum patients, which he used for diagnostic purposes and case reports, but he also showed them to the patients after their treatment had finished to say, “See: this is the state you were in prior to coming to me.” Finally, I’ll just mention, the first medical photography department in the United States was at Bellevue, under the guidance of photographer Oscar G. Mason. He encouraged physicians to use photographs to describe landmark cases, surgical cases, and medical cases. He also helped physicians compile photographs for atlases of disease, and those can be viewed to this day.

Portrait and medical photography seem so distinct from one another. One emphasizes the wholeness and personhood of the subject, while the other captures a specific body part or condition of interest. It’s interesting that early medical photography employed portraiture so heavily. Was the implementation of medical photography in the 19th century about documenting the patient experiences or advancing scientific knowledge?

I think it was a blend of the two. The purpose was definitely to advance scientific knowledge and to show these diseases, and to be able to send these photographs to other physicians around the country or world so that they could learn from unique cases. That couldn’t really be done until the photographic technology allowed for prints to be lighter, smaller, and easier to transport. But when you look at early photographs of the late 19th century, you see very staged poses, with the use of props and backdrops, and they look like formal portrait photographs. So, there was a time when the two really overlapped, as medical photography was gaining its foothold and becoming more of a scientific endeavor and less about artful portraiture.

I know you combed through some really fascinating archives. What types of images did you find? What surprised you most about what you saw?

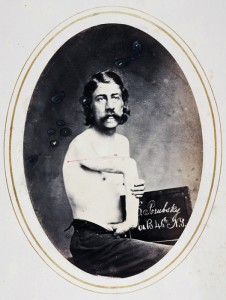

I scoured many places, especially the Internet, because there are so many archival photographs available, but there is nothing like holding an old tattered photograph or a reflective daguerreotype – they almost look like mirrors, and they are really special to see. I was able to travel to the Morbid Anatomy Museum in Brooklyn and also the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia. I spent the day sorting through original medical photographs from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly photographs of Civil War veterans who had an array of amputations and maladies related to their time in the war. What’s so striking is how formal some of the photographs are. A lot of the subjects are dressed very elegantly – with their top hats, bowties, and ruffled shirts – and they’re posing formally, taking a sort of pride in their image and perhaps even their malady, though I can only speculate. I was also surprised, on the other side, to see portraits that seemed to portray patients’ embarrassment or modesty about their illness, whether communicated by a look you can see in their eyes or their decision to cover their faces. Again, I can only speculate why they were covered – maybe it was the photographer’s choice or the physician’s or the patient’s, it’s hard to know for sure.

In our modern medical landscape, patient autonomy is paramount. When we talk about medical photography, what immediately comes to mind for me are issues of consent and privacy. Were these concerns for early medical photographers? How did this change over time?

In the present day, patient privacy, image security, and image quality are definitely paramount. I think early medical photographers were also concerned with image quality, but they employed the techniques of traditional portrait photography to showcase the high quality of their medical photographs, with the props, clothing, and elaborate backdrops. But underlying class issues and race issues came into play as well. There are photos that show patients of different races with similar conditions—a leg amputation, for example – but the black patient is naked and the white upper-class patient is elegantly dressed and wearing full attire. In general, I think patient privacy was less of a concern. You can even find photographs with patients holding up signs with their names and other identifying information.

G. Porubsky, Co B. 46th NY volunteer, photograph by R.B. Bontecou, from Shooting Soldiers: Civil War Medical Photography, by Stanley Burns, MD, published by Burns Archive

Was there one landmark legal case that really altered the course of medical photography with regards to privacy?

It’s hard to pinpoint one case that changed the medical photography landscape but one of the first landmark privacy cases that hinged on photography was Roberson v. Rochester Folding Box Company in 1902. Basically, in this case the Franklin Mills Flower Company had hired Rochester Folding Box to print 25,000 advertisement posters. On these posters was the face of a young girl named Abigail Roberson, a teenager whose portrait had been taken at a photography studio for personal use. She never consented to its public display. Unbeknownst to her, the photos were placed all around town, and she learned of them through friends and family who recognized her. She reported experiencing “great distress and suffering in both body and mind” and she had a nervous breakdown, essentially, because of the embarrassment. While the judge ruled in favor of Rochester Folding Box, her case led to really rampant discussion about privacy and whether or not you own your own image. Over time, a decision related to this case ruled that, in fact, you do own your own image and the rights to decide what can be done with it. There are so many other interesting cases. One is Claymann v. Bernstein in 1940, in which the court ruled that a physician could not use a photograph of a patient’s facial development for the purpose of medical instruction without consent. So even if it was just to be shared between medical students and residents, if consent had not been acquired, then it was not allowed. In a 1961 case in Louisiana, McAndrews v. Roy, a patient sued for an invasion of privacy after a physician published an image ten years after the patient consented. The judge found it unreasonable to publish photos after so much time had elapsed. So the rules we know today stem from several legal cases over time.

The gold standard today is really written consent, right? In these cases, what was the method of consent?

For the case of the elapsed time, I think it was a written consent. But even today not all institutions do written consent—they’ll do verbal and document in the chart, “consent gained verbally,” and some people don’t do consent at all. So, it’s definitely a fine line still, despite all of these cases.

To be continued