(Kent State University Press, 2015)

[Editor’s Note: This is Part II of a dialogue between author and painter Cortney Davis and our Art Editor Laura Ferguson. Part I can be read here.]

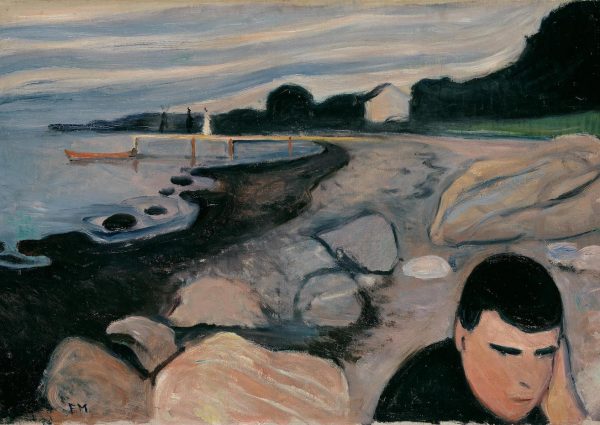

Laura: I’d love to know more about your studio process. I see that some of the pieces are acrylic, some oil, and some include collage. Are they as unselfconscious as they seem? Did they come into being easily and quickly, without a lot of working over – or did you just make it seem that way? You let us feel your pain and your aloneness, you invite us to understand, and you allow us in to your experience. I suspect that may be in part because your paintings are not too perfect and polished.

Cortney: The paintings were painted very rapidly with no working over. I was discharged in mid-July, and the first painting was done at the end of July. Most of the paintings were done in August, six of them, one after the other, usually only a few hours per painting, or less. Three were done in September and two in October. I actually didn’t know what I was doing, technique wise. I painted in my basement in front of an open sliding door, with music playing (most often “The Tallis Scholars Sing Thomas Tallis” or “Agnus Dei, Music of Inner Harmony”). Painting also took my mind off my body (I was having a lot of medication side effects) and I really felt blessed to be alive, to be home, and to be standing by the open door with summer all around me, doing something that seemed totally free from “thought.” When I finished the last painting, I looked at them and wondered exactly how they came about. It seemed there was no “planning” to them, just the painting.

As I recovered, however, by October I could sense the paintings becoming more “thought about” and less unselfconscious. I began to wonder if I was painting “correctly” and I found myself being more careful, more precise with the last two paintings. It was as if when I regained control of my body and my illness was less central, less in command of my day, I also moved, little by little, away from the totally un-thought-about and un-planned-expression that marked the paintings. (The paintings in the book, by the way, are not in the order I painted them – they have been arranged, in the book, in a chronological order to tell the story. I painted the images without rhyme or reason, just painting whatever seemed most urgent.)

The commentaries were added in November and December, at a time when words seemed to return to me, certainly the creative medium in which I was most comfortable and felt most proficient.

Laura: You say that “painting seemed to be all about the body” but also that “painting took my mind off my body.” Is that a contradiction? Did it feel like getting back to your body the way it felt before the illness?

Cortney: Painting felt physical, messy. It felt more like my body if my body only consisted of the senses.

When I painted the last one (which is the last in the book, “Angel Band”) I noticed it was very neat – it felt less messy than the earlier ones – and I knew it was a sign that my head was taking over again. I haven’t really done any more painting since then.

Laura: I wonder if being so vulnerable and out of control, and in a situation that forces us to live in our bodies in a very basic sense, opens us up, frees up that kind of expressiveness. The side of ourselves that needs to get things right becomes unimportant.

I’m thinking about the med students in my Art & Anatomy drawing class. I find myself trying to get them to loosen up, to enjoy being messy, to let go of trying to get it “right” – which is hard, because it’s so important in every other aspect of med school. I think this is related to the issue of control that you bring up. You speculate that “maybe turning illness into something creative is a way of taking control,” and I think that’s true. It allows us to organize the experience, to present it as we see it. But paradoxically, it’s a control that comes from letting go of control. As you say, it works best when it’s messy and just comes out, without a lot of thought or oversight from one’s internal editor.

This tells me that there’s the potential for tremendous creativity in the world of medicine, from both patients and caregivers – and that art is a great way for each to communicate and open up the reality of their experience to the other.