Commentary by Angela Belli, Ph.D. Professor of English, St. John’s University, New York City

For those interested in the debates concerning ethical issues in biomedical science and technology, the domain to visit is the theater. Playwrights frequently focus on the conflict between human values and the rapidly changing technology that has come to prevail in the delivery of health care. They find in contemporary medicine a rich source of material. Current theatrical representations of medical discourse take their authority, language, images, and characters—a whole roster of professionals—all from medicine. A quick perusal of some of the most honored plays of our time reveals how the dramatic conflict, essential to the structure of the work, may be located in an ethical issue to gain the dramatist’s attention.

End-of-life issues, including the termination of treatment, are presented in graphic terms in Brian Clark’s Whose Life Is It Anyway? The question posed in the title is examined from three perspectives: medical, philosophical, and legal. The protagonist, Ken Harrison, is a hopelessly paralyzed young sculptor who is kept alive by mechanical means. Feeling that he has lost all personal and artistic freedom, he concludes that to continue him in such a state is to deny that which distinguishes him as a person. He is opposed by his attending physician who believes that if he allows Ken to die he will be aiding him in an act of suicide. The play turns on one issue: the goal of medical ethics. The resolution confirms the view that if a goal of medical ethics is the restoration of health and if therapy is inadequate to restore those functions that enable one to pursue one’s spiritual goals, then medicine need not assume an aggressive role.

The Elephant Man by Bernard Pomerance presents a study of the need to uphold human dignity. Set in the Victorian Age, the play recalls the life of John Merrick, an actual individual who suffered from what is represented as neurofibromatosis. Severely disfigured he is shunned by society and regarded as a freak. Another view, “the medical gaze,” is introduced when Merrick’s condition comes to the attention of an idealistic young surgeon, Frederick Treves. Aware of the limitations of science to restore his patient to health, Treves undertakes a project in behavioral research, reconstructing a social context for Merrick. The play reaches its climax when the patient realizes that the life of normalcy and freedom created for him are illusory. Merrick’s final triumph lies in his successful act to repossess the dignity he had been denied.

Margaret Edson’s play Wit introduces a heroine whom the audience views during the last two hours of her life passed in a research hospital where she has been a participant in an experimental chemotherapy program. Issues regarding the treatment of the individual as research object give rise to the dramatic conflict, with the heroine confronting various staff members who are anxious to keep her alive for research purposes. In the conclusion of the drama, she regains mastery of her fate and her human will as she overrules the orders of the medical staff with a directive of her own—her DNR request.

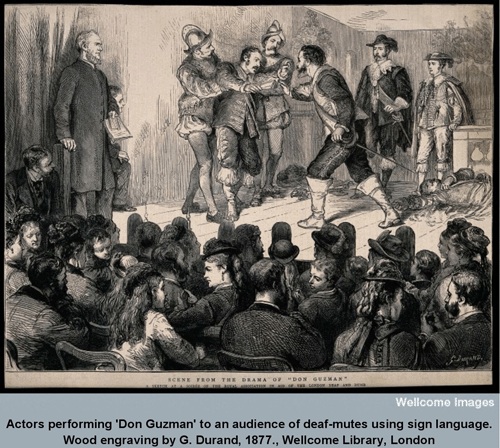

Another heroine who leads us to confront challenging ethical questions appears in Mark Medoff’s Children of a Lesser God. The dramatic focus is on a young woman who has been deaf since birth. Questioning the attitudinal barriers erected by the social majority who fail to communicate with the afflicted and, consequently, conclude that the deaf are mentally inferior, she resists being marginalized and demoralized. Moreover, she insists on using sign language, her preferred means of communication. Choosing her own means of expression is essential to preserving her integrity. Along with the social model, the medical model is recognized in the play. Medicine’s assessment considers the disability to be an illness requiring treatment. A form of intervention such as cochlear implants is frequently advocated. Ethical issues emerge as the varying views of disability give rise to the dramatic conflict.

In his brief, one-act drama The Sandbox, Edward Albee examines ageism, a pervasive canker in the social fabric that targets older individuals. The dramatist locates the bias within American society and spotlights the family structure as a likely site. Further, he examines the stereotype that links ageing with cognitive decline and leads to the erroneous conclusion that the elderly are of little value.

Michael Cristofer’s The Shadow Box offers an artistic view of the philosophy of hospice care, which provides dying patients with an alternative to traditional, impersonal care provided by the established medical system. On stage the dramatist presents an assortment of patients, friends, and family who are torn between accepting a life that has been altered irrevocably for each or disallowing the reality they cannot escape. The drama reveals the value in affirming life and embracing the quality of the time that remains.

The dimensions and cultural ramifications of HIV/AIDS share galvanized discourses within medical, political, and artistic spheres. The theater provides its own sanctuary within which the public may consider the effects of a baffling disease that has shaken the security and confidence in biomedical advances. While constructing an illusory world, drama locates the dialogue in public space, providing a unique opportunity within a communal setting for raising awareness as it promulgates the facts and spurs socio/political action. One play to achieve such goals is Before It Hits Home by Cheryl West. The work recounts the dissolution of an African American family as it reacts to the unexpected crisis in its midst when a son is revealed to be infected.

In searching for valuable tools to encourage greater understanding and knowledge of bioethical dilemmas, one may consider placing copies of some good plays on the desks of medical students, alongside classical texts on medical ethics.

Note: All plays referred to above, except Children of a Lesser God, will appear in the forthcoming (2008) anthology, Bodies and Barriers: Dramas of Dis-Ease, edited by Angela Belli and part of the Literature and Medicine series at The Kent State University Press.

David Henderson Slater

I enjoyed reading your comments, and would be interested in accessing more of your material or joining in web discussions. I use ‘Children of a Lesser God’ in the optional programme I run in Oxford for medical students who come to do an attachment at our hospital centre for people with chronic and severe neurological disease.

Angela Belli

Thank you for your kind attention to my comments. My forthcoming anthology contains additional comments in the introductions that I provide for all plays. It is due to be released shortly, and I’ll be happy to send you a copy as soon as it appears. I would welcome any web discussions as well.